Inclusive growth in Greater Manchester: an agenda for the new Mayor

The first Mayor for Greater Manchester has a chance to show how a major city region can achieve more inclusive growth.

Key points

- The election of a Mayor for Greater Manchester is an opportunity to demonstrate how to achieve inclusive growth – growth that benefits everyone across the city region. Such an approach would have clear economic, fiscal and social benefits.

- Each time an out-of-work benefit claimant moves into a job paying the voluntary Living Wage (which is set with regard to the cost of essentials) the boost to the local economy is £14,400 on average.

- Greater Manchester’s economic strengths are not being converted into inclusive growth. Over 500,000 people are income deprived, and Greater Manchester has the fifth highest rate of income deprivation among England’s 39 Local Enterprise Partnerships. One in four children live in poverty.

- The proportion of households with no-one in work (18.4%) and the rate of economic inactivity (24.5%) are higher than the England average (14.9% and 21.9%). When in work one in five working families rely on in-work tax credits to top up their low pay, substantially higher than the average for England (just over one in seven).

- Creating more and better jobs and connecting people in poverty to opportunities are at the heart of an inclusive growth agenda. This must be supported by improving children’s prospects, as only 52% of five year olds eligible for free school meals have a good level of attainment in Greater Manchester.

- If the Mayor wants to deliver serious progress, their power to influence will be as important as their formal powers; inclusive growth and solving poverty should be central organising principles for their administration. In their first 100 days a cabinet position responsible for inclusive growth should be created, success measures to deliver inclusive growth defined, and stakeholders from business, civil society and public services convened to develop a city-region-wide strategy for inclusive growth and solving poverty.

The election of the first Mayor for Greater Manchester is an opportunity to demonstrate how a major city region can achieve more inclusive growth – that is growth that benefits everyone. Recent political events have demonstrated the need for this. More positively, inclusive growth will enable a stronger and more sustainable economy, reduce the demands on public spending and benefit society.

Greater Manchester is on an ambitious twenty-year journey to become a globally leading region, one that is more productive and innovative and where residents both contribute to higher growth and reap its benefits. It has been at the forefront of city growth and devolution in the UK. But while the city region has seen a marked turnaround in recent decades it still faces significant challenges to creating an inclusive economy.

There are over 500,000 people who are income deprived in Greater Manchester, constituting the fifth highest rate among England’s 39 Local Enterprise Partnerships. One in four children live in poverty. In addition, a significant minority of businesses (22%) report vacancies they cannot fill due to skills shortages. The challenge is not simply to get more people into work: in the UK today 55% of people experiencing poverty live in working households.

The new mayor should continue to put Greater Manchester at the forefront by embracing inclusive growth. Creating more and better jobs and connecting people in poverty to opportunities are at the heart of an inclusive growth agenda.

About this briefing

This high-level briefing uses the best available research and analysis from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) and the University of Manchester’s Inclusive Growth Analysis Unit (IGAU). It provides some ideas and recommendations for how the Mayor can build on opportunities and address challenges to make progress towards an inclusive economy that helps to solve poverty in Greater Manchester. It draws on evidence from experts, policy makers and practitioners, and members of the public, including those with first-hand experience of poverty.

The IGAU will be producing a series of more detailed policy briefings in the coming months looking at what the Mayor can do to deliver inclusive growth in Greater Manchester.

Why would a mayor prioritise inclusive growth?

Attracting, retaining and generating investment to grow the economy is vital for a more prosperous city region. But while growth is necessary, it is not sufficient on its own to develop an economy that works for everyone and where poverty is lower.

A more inclusive Greater Manchester economy would see more people in employment, and more jobs with decent pay and prospects, bringing economic and social benefits. Each time an out-of-work benefit claimant moves into a job paying the voluntary Living Wage (which is set with regard to the cost of essentials) the local economy is boosted by £14,400 on average.

Education and skills are vital for people to make the most of economic opportunities, but children from low-income backgrounds achieve worse results at every stage of their education compared to those from better-off homes. This deprives businesses of talent. It also reduces people’s earning potential, reduces the tax take and increases the risk that poverty will be passed from one generation to the next.

Inclusive growth that helps to deliver lower poverty would also release resources that could be put to more productive use. An estimated £1 in every £5 spent on public services is linked to poverty, with the costs falling heavily on the health service, education and the police and criminal justice system.

Ultimately, poverty is harmful to those who experience it, scarring their prospects, worsening mental and physical health and shortening lives. Healthy life expectancy is nine years shorter in Manchester City compared to Stockport for men, and 11 years shorter for women.

In other words, growing the economy and reducing poverty are not separate areas of activity. Poverty is caused by unemployment, low wages and insecure jobs, lack of skills, family problems, an inadequate benefits system, and high costs (especially for housing). Developing a more inclusive economy will make a significant contribution to solving poverty in the UK, as well as making Greater Manchester a better place to live.

An overview of prosperity and poverty in Greater Manchester

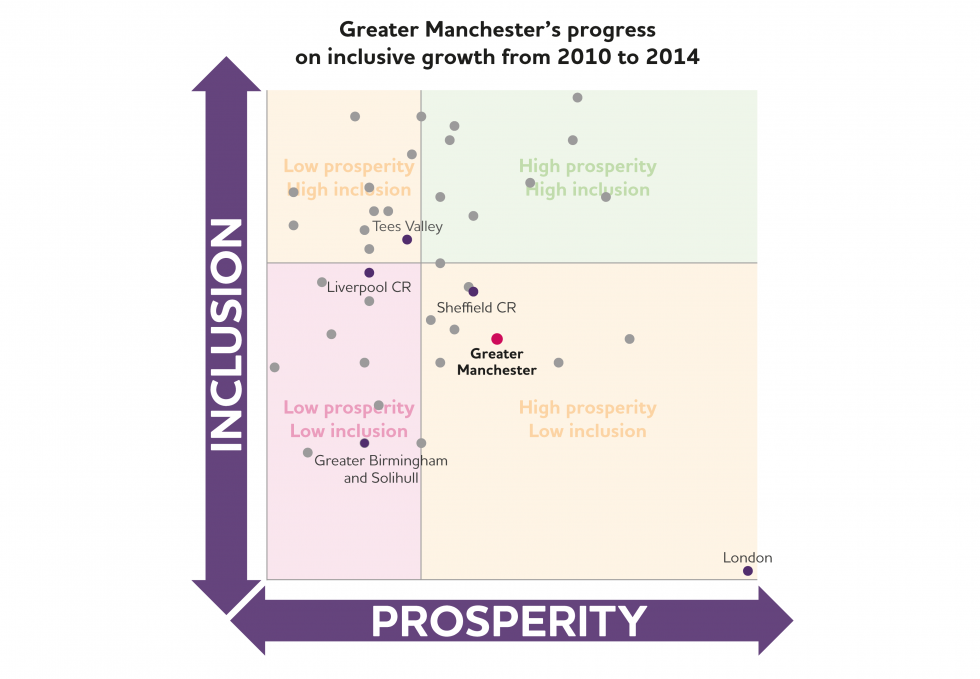

In recent years Greater Manchester has made significant progress relative to other areas on prosperity – economic growth, employment opportunities and human capital. Yet as JRF’s Inclusive Growth Monitor shows it has made comparatively less progress in making these gains inclusive – addressing labour market exclusion, living costs and incomes at the bottom end. In Greater Manchester one in four children are growing up in poverty, compared to a national average of one in five. In addition, 11% of the population receive out-of-work benefits, and one in five families receive in-work tax credits to top up low pay. For the country as a whole these figures are 8% and 18% respectively.

| Greater Manchester | England | |

|---|---|---|

| Prosperity | ||

| Gross Value Added per capita (£) | 21,600 | 26,200 |

| Jobs per 100 residents | 78 | 83 |

| Businesses per 1,000 residents | 37 | 44 |

| Inclusion | ||

| Employment rate | 70.5 | 74.0 |

| Unemployment rate | 6.5 | 5.1 |

| % out of work benefit receipt | 10.7 | 8.4 |

| Median gross weekly pay (full-time) | £494 | £545 |

IGAU’s report Inclusive Growth: Opportunities and Challenges for Greater Manchester looks at these issues in more detail.

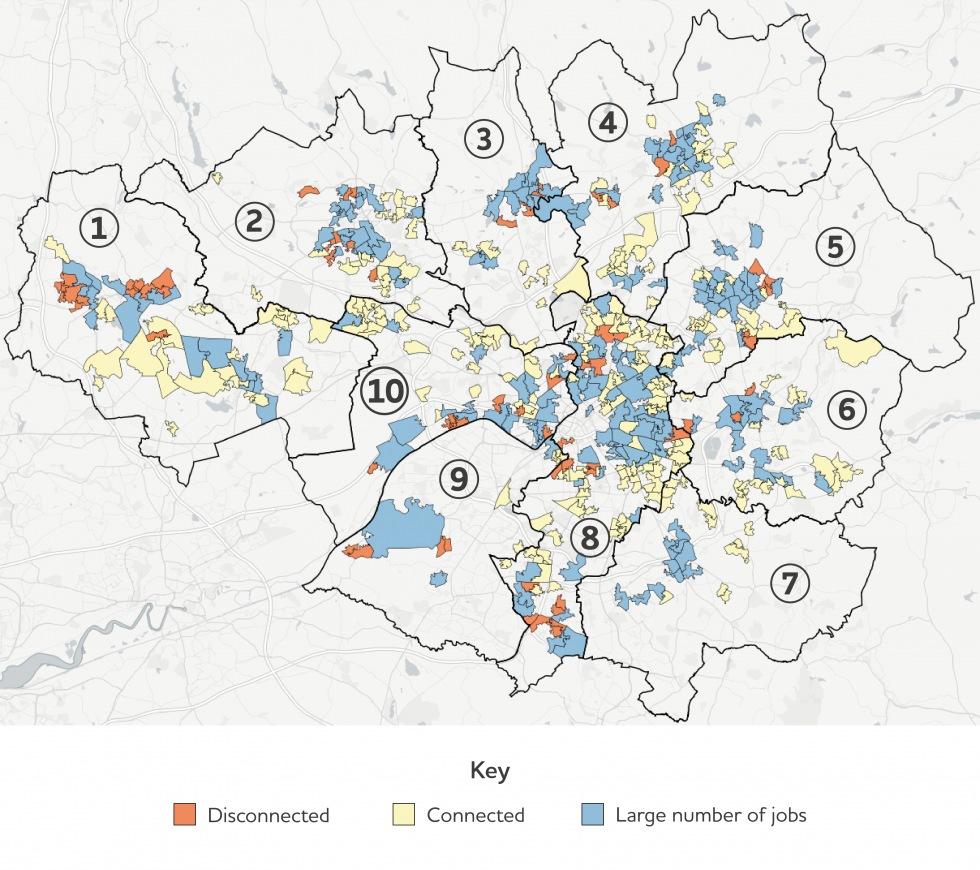

Inclusive growth requires not only the creation of good jobs, but for people in poverty to be connected to them. Doing this requires a detailed understanding of what drives labour market exclusion in Greater Manchester. The map below shows the places in the city region that are in the fifth most deprived nationally, and their relationship to local labour markets.

There is a notable ring of deprived areas around the city centre. Most of these are ‘primary employment zones’ – deprived areas where there are more jobs than people – and the vast majority of the rest are found to be well connected to local labour markets. This analysis suggests that transport connectivity is not the key barrier to work for people living in these areas; local policymakers need to focus on other barriers to work, such as skills, health and caring responsibilities.

Looking beyond the inner ring, there are pockets of deprived areas that are geographically disconnected from jobs. Transport policy should focus on connecting people in these areas to opportunities nearby.

Neighbourhoods in the Greater Manchester area:

- Wigan

- Bolton

- Bury

- Rochdale

- Oldham

- Tameside

- Stockport

- Manchester

- Trafford

- Salford

Note: the map shows the travel-to-work typology from 'Overcoming deprivation and disconnection in UK cities' for the most deprived 20% of LSOA's nationally located in Greater Manchester.

How can a mayor help to solve poverty through an inclusive growth agenda?

An inclusive economy - a strategy that includes the bottom end of the labour market

For an inclusive economy, the number and quality of jobs created is every bit as important as the skills and capabilities of local residents. All too often the bottom end of the labour market is overlooked in local economic strategy.

Greater Manchester performs relatively well compared to other major UK cities on the number of jobs per person and the number of private sector businesses per 1,000 people. Yet median full-time wages are £50 per week lower in Greater Manchester (£494) than they are nationally (£544); they are also slightly lower than those in the other mayoral regions. They range from £460 for people living in Tameside to £601 in Trafford. Nearly a quarter (23%) of workers in Greater Manchester were paid below the voluntary Living Wage (which is set with regard to the cost of essentials) in 2014 (similar to the England average), and the proportion of the population claiming in-work tax credits is four percentage points higher than the England average. Good jobs and higher wages are essential to address in-work poverty and deliver inclusive growth.

A Mayor should ensure a more balanced ‘whole economy’ approach. Alongside the targeting of traditional high growth sectors, activities to raise the productivity and pay in low pay sectors should also be a priority. The potential of the social economy should also be part of the Mayor’s thinking. The devolution of business support services and the creation of the investment fund are opportunities here.

To help deliver better jobs JRF recommends:

Raising productivity in low pay sectors – increasing the productivity of low-paid workers is a route to higher pay for them and a more prosperous economy for everyone. Lagging productivity in low-pay sectors accounts for around a third of the UK’s productivity gap with leading Western European economies. Greater Manchester has already identified health and social care, retail, hospitality and tourism as among its priority sectors. The Mayor should work with businesses and industry bodies in these sectors to develop strategies to increase productivity. Promising approaches to increasing productivity in low-pay sectors include: taking a broader view of innovation to include processes, design and marketing; improving management skills through training and business support services; and encouraging business models that ensure firms invest in employees’ skills and think long term. The Mayor’s business support and skills powers should be used to support this activity.

Support growth sectors to reduce poverty – as part of the business support offer, draw on international evidence to test a sector employment programme approach. This can be an effective way of supporting people into better jobs, while supporting growth sectors to tackle shared problems such as skills shortages. Successful programmes share a number of characteristics:

- Focused on business needs: delivered by organisations that understand the selected sector, and can secure buy in from businesses on the basis of identified problems such as skills shortages or high staff turnover.

- Strong partnership working: able to work with training providers and employment support providers to broker a bespoke response to business needs.

- Offer personalised support for individuals: work with low-paid employees and unemployed people to access the opportunities being created.

Connect economic development and poverty reduction – Manchester City already has considerable experience of using procurement processes to support the local economy and businesses by buying locally. This way of thinking should be extended to job creation. Where local economic development activity leads to new jobs (both when new developments are being built, and the jobs that then follow), or local anchor institutions (the biggest local spenders and employers such as local authorities, universities, NHS) are recruiting staff, they should make sure local people with barriers to the labour market benefit. The Mayor can support this to happen by using planning obligations more systematically and brokering training and employment support packages to connect people to opportunities.

The IGAU will be producing more detailed briefings on local economic strategies and wages and work later in the year.

Planning for inclusive growth

The cost of essentials – especially housing – is as important for solving poverty as increasing incomes. Currently housing is more affordable in Greater Manchester compared to the national average, although buying a home remains out of reach for low-income people, with a low-cost home about five times the income of a typical low earner (compared to a national average of seven times). Continuing to increase the supply of housing across all tenures will be important to ensure economic success does not create a worse affordability problem in Greater Manchester.

The draft Greater Manchester Spatial Framework sets out ambitious housing targets and prioritises building on brownfield sites. As in other northern cities, many of these sites require remediation, which acts as a key constraint on housing delivery. The new Mayor should seek flexibility over use of the new Housing Infrastructure Fund within Greater Manchester, so that bids can be submitted for remediation of housing sites with existing transport infrastructure.

Alongside the cost of housing, affordable access to jobs and essential services enables people to escape poverty. The devolution of a consolidated transport budget, bus franchising and smart ticketing will present significant opportunities for the Mayor in this respect.

To plan for inclusive growth JRF recommends:

Developing homes with living rents – the Mayor should try to secure greater flexibility on how Homes and Communities Agency investment can be spent in Greater Manchester. This would enable development of new homes to rent and buy based on a Greater Manchester Living Rent, which is linked to local incomes, making sure homes are affordable for low income workers.

Improving standards in the private rented sector – the number of households living in the private rented sector in Greater Manchester increased by 63% between 2001 and 2011. Nationally, one in three homes in the private rented sector does not meet the Decent Homes Standard. The Mayor should demand the return of selective licensing powers to local authorities, and promote integrated private rental sector services to tenants and landlords that accredit landlords, offer training and information, enforce standards, provide a tenant matching service, access to low cost loans to fund improvements to meet the Decent Homes Standard, and a limited rent guarantee service.

A Housing First approach to homelessness – the rate of homelessness in Greater Manchester is 15.1 local authority case actions per 1,000 households, above the national average (11.2 per 1,000). A Greater Manchester-wide focus on prevention should be coupled with scaling up Housing First as the default approach for homeless adults with complex needs, learning from the Greater Manchester pilot scheme already underway. Housing First involves moving people rapidly into ordinary housing with tailored support. It improves outcomes for the individual and offers potential for savings across public services, including health.

Connect people in poverty – use new transport powers to prioritise connecting disconnected deprived areas to job opportunities, and make poverty reduction an explicit part of the transport authority’s remit.

Connecting more people to economic opportunity - support people to move into work

Greater Manchester has a higher proportion of households with no-one in work (18.4%), a higher unemployment rate (6.5%), and higher proportion of working age adults who are economically inactive (not looking for work because they are studying, looking after family, disabled or sick - 24.5%) than England as a whole (14.9%, 5.1% and 21.9% respectively). However, on each of these dimensions, Greater Manchester does perform better than the other cities electing mayors.

The Mayor will have powers over employment support for people with significant barriers to work, including the Working Well programme, which has led the way in linking up personalised employment support and health services.

To support people to move into work JRF recommends:

Employment support incentivised to focus on poverty – all employment support services should be given the same core target to reduce poverty through higher employment and earnings. This will help to focus activity on the outcomes that matter most for poverty and inclusive growth.

Trialling employment support programmes that build on the evidence – the Mayor should learn from the Working Well pilot and continue to build the evidence base for interventions that work for long term unemployed, economically inactive and disabled people. These include the confidence and motivation boosting role of personal advisers and peer support, work experience and work trials, and Individual Placement and Support schemes (where rapid entry into a mainstream job is complemented by on-the-job training and ongoing support to sustain employment) for people with learning difficulties and severe and enduring mental health difficulties. Specialist or voluntary and community sector providers are often best placed to deliver such services. Demonstrating impact will also help to build a case for devolving further responsibilities for employment support, to include those with more modest barriers to work, who are at risk of not being well served by the Government’s current plans for reform.

Support people to progress in work

Training and skills will be a crucial tool for promoting inclusive growth and solving poverty. This is an area where the Mayor will have significant powers.

With over 70% of the working age population qualified to NVQ level 2 or above and over 40% of the population employed in higher level occupations, Greater Manchester performs relatively well compared to other city regions electing mayors. However, it still lags a little behind the English average (73% and 45% respectively). However, 180,000 working age people have no qualifications, and the proportion of people with low qualifications is high in some areas. In 2015, 37.3% of people in Oldham and 33.9% in Rochdale had qualifications below NVQ level 2, compared with 18.8% in Trafford.

Greater Manchester’s flexible labour market requires workers to be highly adaptable, meaning access to training and re-training throughout working life will only become more important. And training can have a demonstrable impact on earnings: moving from an NVQ level 2 to 3 qualification is associated with between a 2 and 15 percentage point increase in the chances of employment and between a 9 and 11 percentage point increase in earnings.

The challenge is to get the incentives in the system right so that the training and skills system both responds to the needs of employers and supports the drive to help people move into work and to move on up to a better job once they are in work.

To support progression in work JRF recommends:

Focus on access and quality in apprenticeships – good apprenticeships help people to get on, but too many remain poor quality with little labour market value. The focus needs to be on increasing the quality alongside increasing the quantity of apprenticeships. Starting with apprenticeships in priority growth sectors, the Mayor could initiate a process to assess their quality and work with learners, businesses and training providers to develop an Apprenticeship Charter setting out quality standards. They should also monitor access to good apprenticeships by people from ethnic minority backgrounds, disabled people and women to make sure opportunities are shared. Ultimately pushing for greater powers over apprenticeship funding including the apprenticeship levy would enable the Mayor to ensure apprenticeships are focused on delivering better employment and earning outcomes.

Reorient training and skills provision to solve poverty – the training and skills system could make a greater contribution to reducing poverty if the focus was on outcomes such as high employment, earnings and progression to further learning. Some funding to providers should be contingent on the outcomes they achieve, to incentivise a stronger connection to the needs of businesses and individuals.

Trial services to support people to progress in work – simply getting a job is not always sufficient to escape poverty, and four out of five low-paid workers fail to fully escape low pay over 10 years. Greater Manchester should make the ability to get on a key part of its offer, and trial different approaches to supporting progression in work. Trials should combine coaching and support from advisers able to foster links with employers, well-targeted training linked to realistic career progression opportunities and financial incentive payments.

The IGAU will be producing a more detailed briefing on education and lifelong learning later in the year.

Improve children’s prospects

Today’s children are the citizens, parents and workers of the future. Making sure all children get the best possible start in life and achieve well in their education is fundamental to inclusive growth and solving poverty. The early years form a foundation for future educational achievement, but children from low income backgrounds are already falling behind by age five, and the higher child poverty rate in Greater Manchester means more children are at risk. Only 52% of children eligible for free school meals achieve a good level of development aged five in Greater Manchester.

Families and communities can provide a vital defence against material and emotional hardship, often offering the first and most reliable sources of support, advice and information. Family stability enables children to flourish, while family breakdown increases the risk of poverty. The goal should be to help parents stay together where possible, and when they cannot the aim should be to help parents to separate and parent well.

The Mayor will be responsible for a Life Chances Investment Fund. This, along with the power of the Mayor to convene and to influence, can be used to support families and give children a good start.

JRF recommends:

Championing the creation of Family Hubs – revitalise the offer of Children’s Centres and family support services by bringing them together into family hubs. Parenting and relationship support should be a priority. This universal service can then be used as a platform to identify families where early intervention can help prevent problems deepening. Such a service will also help to identify families facing more complex challenges where more intense support is needed.

A whole family approach for families with complex needs – where families have complex needs – such as substance abuse, mental health conditions, homelessness, experience of violence and criminality – evidence indicates successful approaches that should drive programme design. These combine a worker dedicated to the family, practical ‘hands on’ help, a persistent, assertive and challenging approach, building a sense of common purpose and agreed actions.

Focus attention on quality in childcare – good quality childcare helps children from deprived backgrounds start school ready to learn. At age five, children who have had high-quality childcare for two to three years are nearly eight months ahead in their literacy development than children who have not been in pre-school. The Mayor should use their soft power to keep a focus on the quality of childcare; activities that would help include:

- An early excellence fund to support training of childcare providers so there is a graduate in each setting, starting with those that are delivering free childcare to two year-olds from deprived backgrounds.

- Connecting providers to early intervention services.

- Increasing the number of early years Special Educational Needs Coordinators to provide advice and support to childcare providers.

The IGAU will be producing a more detailed briefing on education and lifelong learning later in the year.

Using the soft power of the office of Mayor: leadership and governance

Inclusive growth is an agenda, not a new policy initiative – and it is an agenda which will require strong leadership from the Mayor. The Mayor can be the champion of inclusive growth: raising ambition, shaping strategy, inspiring action, marshalling resources, fostering collaboration and asking difficult questions. The Mayor can convene and galvanise activity, drawing in actors from across the public, private and voluntary and community sectors. This includes holding central government to account for actions that impact on poverty and prosperity in Greater Manchester, and continuing to fight for the devolution of powers and resources to enable the Mayor to solve poverty.

The ability to influence will be as important as how the Mayor uses their formal powers in areas such as employment support, skills and training, transport and housing.

JRF recommends the Mayor:

Define and measure success. A new vision for a more inclusive local economy needs to be underpinned by a new approach to measuring and monitoring performance. This means moving beyond simplistic economic measures of success to capture who actually benefits from growth. JRF, with Sheffield Hallam University, has begun to develop a tool for monitoring inclusive growth and the IGAU will produce a more detailed briefing on indicators and targets for inclusive growth later in the year. A new approach to how the costs and benefits of projects are appraised and how value for money is calculated would also enable major capital and revenue investment decisions to contribute to inclusive growth objectives.

Lead by doing – the Mayor must lead not only through words but through action. A powerful way to influence others is by demonstrating what can be done. The potential for collaboration across local anchor institutions to set the tone for the economy is huge. The Mayor can play a pivotal role in corralling anchor institutions to ensure their practice as employers and procurers of goods and services is geared towards creating a more inclusive local economy.

Make inclusive growth a shared agenda for the whole city region. Inclusive growth is not just the job of the Mayor, but the whole city region – its businesses, employers, institutions, service providers and communities. The Mayor should help champion a direct role for citizens here too. An inclusive growth strategy must draw on the ideas and direct experience of local people, communities and voluntary and community sector organisations. This should include people with experience of poverty, though projects such as the Salford Poverty Truth Commission.

The first 100 days

A Mayor committed to solving poverty and delivering more inclusive growth should make these goals the organising principles for the mayoral team. Their first actions should be to:

- Create a cabinet position with responsibility for Inclusive Growth, integrating social and economic policy.

- Set ambitious targets to focus action on the employment rate, and boosting educational attainment from the early years to adult skills.

- Convene stakeholders across business, economic development, employment and skills providers, education and early years providers, other public service providers and civil society to develop a city-region wide strategy for inclusive growth and solving poverty.