A Minimum Income Standard for the United Kingdom in 2024

The Minimum Income Standard is a vision of the living standards that we, as a society, agree everyone in the UK should meet.

This report from the Centre for Research in Social Policy (CRSP) at Loughborough University sets out what households need to reach it in 2024.

- Key points

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Rebasing MIS in 2024 – methodology

- 3. Rebasing MIS in 2024 – qualitative findings

- 4. MIS budgets in 2024

- 5. How MIS compares with incomes on benefits and the National Living Wage

- 6. Conclusion

- Notes

- Annex: MIS in brief

- References

- Acknowledgements

- About the authors

- How to cite this report

- Key points

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Rebasing MIS in 2024 – methodology

- 3. Rebasing MIS in 2024 – qualitative findings

- 4. MIS budgets in 2024

- 5. How MIS compares with incomes on benefits and the National Living Wage

- 6. Conclusion

- Notes

- Annex: MIS in brief

- References

- Acknowledgements

- About the authors

- How to cite this report

Key points

Despite the challenges of the past few years, including the cost of living crisis, this report shows that people still think that everyone should be able to do more than merely survive. Meeting basic needs alone is not enough for people to thrive. They need to be able to connect with others, have choices and opportunities and feel included in society. For many people in the United Kingdom (UK), there continues to be a gap between what they have and what they need for a decent standard of living.

Indeed, more people are falling well short of a Minimum Income Standard (MIS), including many who are working. Reporting findings from April 2024, this research provides a picture of what people agreed a minimum socially acceptable standard would enable people to have and do. Future updates will help to assess whether the new government’s objective to improve living standards has enabled more people to meet their needs.

Here are the key points from the report:

- MIS continues to provide a unique and distinctive way through which to observe and track the impact of social, economic, political and cultural change on our shared vision for higher living standards, so we can all live with dignity in the UK.

- In 2024, we have rebased (that is, developed from scratch) budgets for all households in the same year, for the first time since MIS was introduced in 2008.

- Working-age households (both with and without children) have identified a need for additional financial resources to meet health needs, reflecting the difficulty of accessing help via the National Health Service (NHS).

- A single person needs to earn £28,000 a year to reach a minimum acceptable standard of living in 2024. A couple with 2 children need to earn £69,400 a year between them.

- April 2024 saw an inflation-based increase in benefits of 6.7%. However, Council Tax, water and broadband prices all rose in April.

- The final cost of living payments, intended to help those households most likely to be affected by rising costs, were made in February 2024, with no announcements of further support being planned.

- Without these payments, working households may struggle to meet the challenges posed by inflation, even though that fell between May 2023 and April 2024 and is forecast to reach 2% in the second half of 2024.

- Despite this, a couple with 2 children, where one parent is working full-time on the National Living Wage, and the other is not working, reached only 66% of MIS in 2024, compared with 74% in 2023.

1. Introduction

Since 2008, Minimum Income Standard (MIS) research has provided a living standards benchmark. It sets out what the public agree is needed to live in dignity and the income required to meet this standard. As a data series it provides a basis for monitoring how many people are falling below, and how far below, this level (Padley et al., 2024).

This MIS report reflects public consensus on what is needed for a dignified socially acceptable standard of living in 2024, developed from group discussions held between May 2023 and March 2024. It is rooted in what people were experiencing at that time and what resources and priorities were considered important for households to be able to thrive, with all items priced in April 2024. Over much of the fieldwork period, food and fuel prices remained high, and the cost of living crisis continued to contribute to an ongoing sense of uncertainty.

Following the general election of 4 July 2024 there has been a new focus on improving living standards, with bills introduced in the King’s Speech relating to children’s wellbeing, renters’ rights, domestic fuel, public transport and mental health, among many others. This year’s MIS report provides a valuable point of comparison, not just with previous years but also as a pre-Labour government baseline. Over the following years, MIS research will help to assess what progress has been made, and continue to inform public and political discussions about what kind of society we want to live in, and how we might get there.

MIS establishes a threshold below which the public agree no one should fall if they are to meet their minimum needs and participate fully in society. This report draws on more than 130 hours of discussion with members of the public held throughout the UK from May 2023 to March 2024. These deliberative groups of parents, pensioners and people without dependent children came together to decide what is needed to meet a minimum socially acceptable standard. This standard includes material needs such as housing, clothing, food, furniture, toiletries and other household goods, and more intangible needs, such as communication, connection and social interaction.

Update schedule

Up to 2024, we updated MIS on a rolling programme, alternating between conducting new primary research in one year and uprating the budgets by inflation in the next. New participants were involved in the primary research every 2 years, keeping MIS relevant to today’s society.

Since 2012 we have been combining review (where we convene new groups to assess existing lists to find out what has changed since the last research) with rebasing (starting from scratch), alternating households with and without children in each process, with inflation uprating in between years (see Table 1 for details from 2020 to 2023).

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Households without children | Review | Inflation uprating | Rebase | Inflation uprating |

| Families with children | Rebase | Inflation uprating | Review | Inflation uprating |

From our previous MIS work, we could see that during prolonged periods of economic uncertainty and instability there was a risk that continuing to rebase the budgets at different times would make it increasingly difficult to get a clear picture of how living standards were changing for and across all demographic groups. For these reasons, the 2024 update became a full rebase across all households – the first time that all household budgets have been rebased within the same year since the first MIS report was published in 2008. This represents a new landmark in the MIS series, giving an opportunity to reflect more widely on what the public think is needed for a minimum socially acceptable standard of living in the contemporary UK.

The MIS updating cycle has therefore changed so that it continues to provide comprehensive new research across all household types every 2 years, but with a different structure to previously. In odd-numbered years, MIS budgets will continue to be uprated by inflation, applying changes in broad categories of the Consumer Prices Index (food, clothing and so on) to the MIS budget categories. Every 2 years (even-numbered years), as before, all budgets will be subject to new primary research, alternating between review and rebase (see Table 2). A MIS review asks groups to confirm or amend existing budget lists, but only changes items where there is a clear consensus and rationale for doing so, in other cases continuing to uprate with inflation. Rebasing of MIS budgets, on the other hand, is a much more exhaustive and in-depth exercise, repeating the original research and pricing items from scratch.

| 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Households without children | Rebase | Inflation uprating | Review | Inflation uprating | Rebase |

| Families with children | Rebase | Inflation uprating | Review | Inflation uprating | Rebase |

2. Rebasing MIS in 2024 – methodology

Rebasing centres around a succession of discussion groups with the general public, using the case studies and the definition of a minimum acceptable standard of living that groups established in 2006. As in all previous MIS research, each group is asked to consider what goods and services someone needs in order to have a minimum acceptable standard of living.

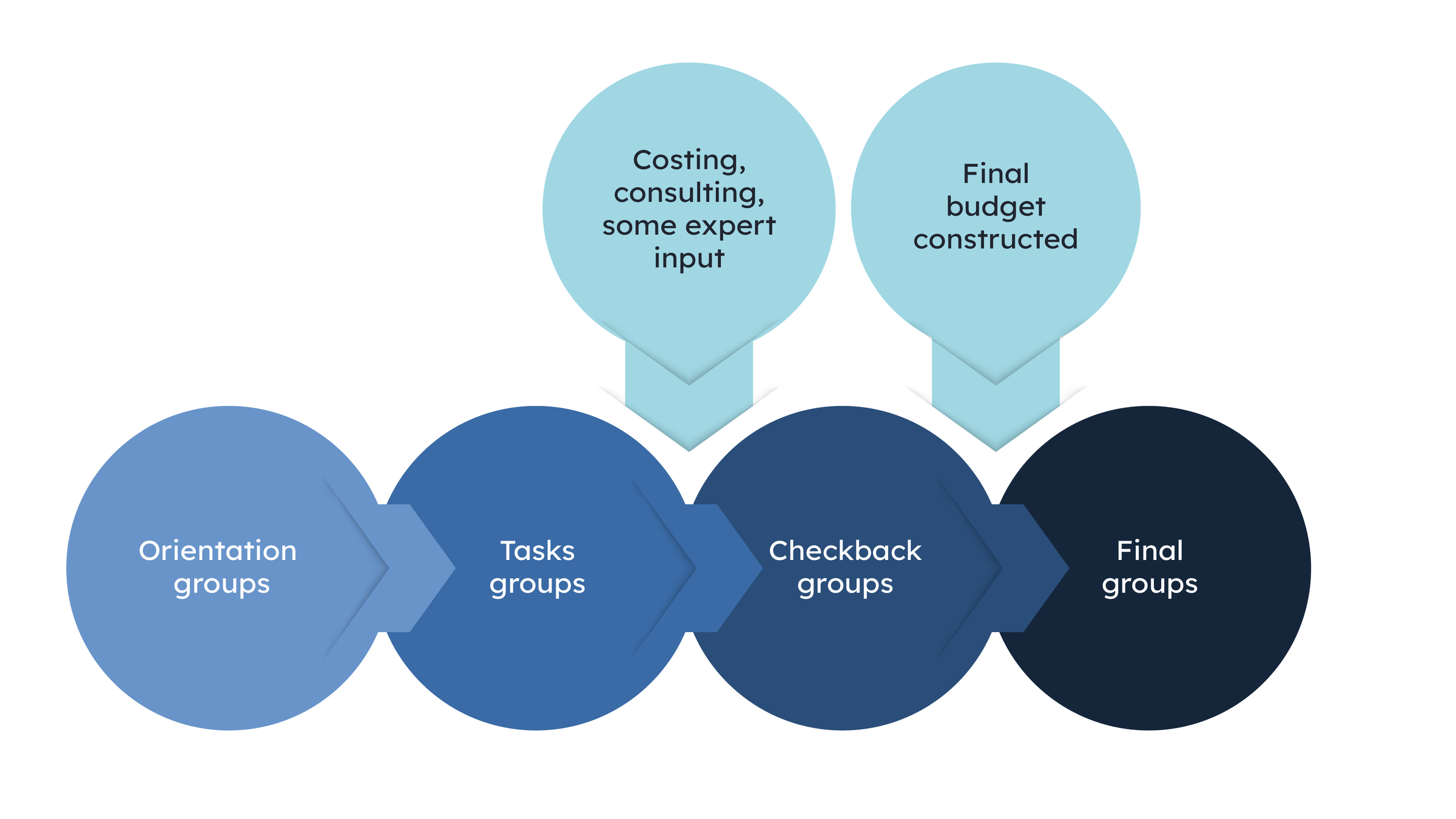

Groups are held in stages:

- orientation groups

- task groups

- checkback groups

- final groups.

Group members are drawn from the family types and individuals under discussion in each case. At each stage, a new set of participants are recruited for the groups. At various points before and after these ‘general public’ groups, ‘expert professionals’ are consulted to provide input to specific areas of the budgets (chiefly domestic energy and nutrition). Figure 1 sets out the stages in the MIS process.

3. Rebasing MIS in 2024 – qualitative findings

The rebase groups are of different durations depending on the function of the group. The first-stage groups (orientation groups) are 2 hours long and are used to check some key principles, particularly relating to housing, transport and, in the case of households with children, childcare. Decisions from these groups affect the assumptions used in groups regarding the size and tenure of housing for different household types, and inform subsequent conversations around transport and (where relevant) childcare.

The task groups each spend 6 hours discussing the needs of a case study individual (that is, a made-up example of someone from the same demographic group as the participants). In groups looking at the needs of children of particular ages, we talk to parents who have children of the relevant age (that is, infant/toddler, preschool, primary school or secondary school aged children).

All of the discussion groups conducted in MIS research have a deliberative as well as a discursive role. They are convened to negotiate consensus and make detailed decisions relating to the needs of individuals and households. This is achieved by identifying and checking which items to include across 4 waves of groups. In this process, each successive group either corroborates or amends the decisions of previous ones. Groups typically comprise 7 to 10 people from a mixture of socioeconomic backgrounds, but all participants within each group are from the category under discussion. This correspondence between groups and the cases they consider and discuss in demographic terms helps them take on the role of ‘experts by experience’ in the daily needs of those under discussion. For example, a group of parents of preschool children feel well equipped to reflect on what a child of this age group requires.

All groups are audio-recorded and transcribed. The transcripts are used in conjunction with flipcharts, which are annotated during the group discussions to compile the decisions made into lists of goods and services, the retailers these goods and services might be purchased from, the lifespan of all goods and services or how often these need to be replaced, and the quality and quantity of items. The transcripts are thematically analysed and used to illustrate the decision-making processes and discussion points that inform the MIS budget areas presented in each year’s report.

See Table 3a-3d for more detailed information about the composition, number and duration of the groups.

Despite the complexity of recruiting and conducting research in a large number of locations, we continue to hold groups in a greater number of towns and cities across England and in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. This has helped to demonstrate that people’s needs and how they meet them in urban UK do not vary significantly depending on where they live (we know rural communities have additional and different needs relating to how those needs are met), so that MIS continues to be a standard applicable to the whole of the UK.

Stages in the MIS rebase process

| 2 orientation groups |

|---|

| Single and partnered working-age adults without children |

| Mix of lone and partnered parents of children aged under 18 |

| 6 groups of single and partnered working-age adults without children and single and partnered pensioners | 7 groups of lone and partnered parents of children aged under 18 |

|---|---|

| Single working-age men without children | Lone parents |

| Single working-age women without children | Partnered mothers |

| Partnered working-age adults without children | Partnered fathers |

| Single female pensioner | Parents of 0-23 month-olds |

| Single male pensioner | Parents of 2–4-year-olds |

| Partnered pensioners | Parents of primary school children |

| Parents of secondary school children |

| 4 x 2 (8 total) groups of single and partnered working-age adults without children and single and partnered pensioners | 1 x 5 and 1 x 6 (11 total) groups of lone and partnered parents of children aged under 18 |

|---|---|

| Single working-age adults without children (mixed) | Lone parents |

| Partnered working-age adults without children | Partnered parents (mixed) |

| Single pensioners (mixed) | Parents of 0-23 month-olds (Phase 3a) Parents of 2-4 year olds (Phase 3a) Parents of 0-4 year olds (Phase 3b) |

| Partnered pensioners | Parents of primary school children |

| Parents of secondary school children |

| 2 groups, one of single and partnered working-age adults without children, and one of single and partnered pensioners | 2 groups of lone and partnered parents of children aged under 18 |

|---|---|

| Single and partnered working-age adults without children | Lone and partnered parents |

| Single and partnered pensioners | Mix of lone and partnered parents of children aged under 18 |

The social and economic context in which we live affects how much it costs to achieve a minimum acceptable standard of living. The cost of living crisis means that many UK households today face high and rising costs for goods and services, while incomes have not kept up. Continued cuts to public spending and services, welfare retrenchment and labour market challenges have affected household incomes and expenditure. The way that people obtain everyday goods and services has also changed: for example, there has been a notable rise in healthcare borrowing, with UK households using credit packages to self-fund operations and diagnoses, in an attempt to mitigate the challenges of accessing healthcare via an increasingly stretched National Health Service (NHS) (Gabert-Doyon and Quinio, 2024).

Amid these financial challenges are personal costs, with growing health inequalities affecting people across the life course in the UK (Marmot, 2024). However, although MIS does not exist independently of these realities, it is unique in its focus on asking people to think about what a decent living standard is, rather than what people below it might lack. In this way, it differs significantly from other poverty and deprivation-based research and gives us a vision of what people think living in the UK with dignity could and should be like.

This chapter draws on the qualitative data from the deliberative groups in 2024. Much of the ‘basket’ of household goods and services that comprise MIS budgets has stayed the same, which is what we have come to expect over time. A changing economic landscape does not immediately result in a radical rethink among the public about what constitutes a decent living standard.

Living through what seem like particularly precarious times also does not fundamentally change the food people cook and eat and the type of furniture they use in their homes. We continue to check this by carrying out new primary research that includes detailing clothing, toiletries, kitchen equipment and many other everyday household items, and we can see that these kinds of things tend to remain largely similar from one iteration of the MIS research to the next, even though, in some cases, prices may have increased substantially.

Effects can take time to play out, though, as we discovered following the global financial crash in 2008, where subtle changes over the following 9 years’ worth of research pointed at adjusted expectations, availability of services and social and cultural norms (Davis et al., 2018). In 2024 we can see how changes caused by external events and financial pressures affect what people consider to be necessary to reach a minimum socially acceptable standard of living.

Thee remainder of this chapter offers an overview of the contents of the MIS ‘baskets’ arranged by broad category, and summarises the decisions that the deliberative groups made. Decisions to include or exclude particular items are explained in the context of the discussions the groups had and the rationales they used, and how these resonate with evidence from other sources, for example of changes in services, norms and/or consumer behaviour.

The goods and services included in MIS 2024 household budgets are discussed in the following sections:

- housing

- domestic fuel

- food and drink

- clothing

- household goods

- household services

- health and personal care

- transport and travel

- social and cultural participation.

Housing

The first task for groups was to decide what kind of accommodation would be suitable as a minimum for different household types, in terms of tenure (rented or owned) and size (expressed as a flat or a house and the number of bedrooms that occupants need).

As they have done so since the MIS research was first published in 2008, groups unanimously agreed that, as a minimum, rental accommodation would meet households’ needs. Parents agreed that social housing would be acceptable to meet the needs of households with children. It was seen as offering greater stability and security than renting from a private landlord, and there were concerns about the quality of housing stock in the private sector. Major barriers to social housing included the application process itself, lengthy waiting lists, a shortage of suitable properties and reservations about the lack of choice in terms of location.

Research transcript - parents, Sheffield:

Researcher: So, the first question is erm what kind of accommodation would meet their needs as a minimum? In terms of what sector. So do they need to own their own home as a minimum or is that a ‘nice to have’? Is renting OK?

Woman 1: Renting is fine.

Woman 2: Yes.

Woman 3: Social housing.

Woman 1: Social housing… and then private renting is the ‘nice to have’.

Man 1: I must admit, I was listening to the radio the other day, I think social housing sounds better than private… just because of the fact that, well, I say fact, you hear all of these horror stories about mould growing in these private rentals and the council doing nothing.

Woman 2: And also as well, do you know after Covid you’re not very secure in a private rented house anymore. I know so many people now that have been kicked out, well, or just can’t afford to pay the rent anymore because it has gone from £500 to £900 [a month] – it is ridiculous.

[…]

Woman 1: There is long waiting lists [for social housing] and then I think when you eventually get on, you normally get put in an area that you don’t want to be in.

Woman 2: Where you don’t know anyone.

Woman 1: Yes where you don’t know anybody, you have moved away from your family if you have got any up here, and the kids might be at school but then they will have to move schools, that kind of thing, there is quite a lot of disruption.

Woman 3: I don’t think they make it easy. I have not had to do it recently, but I think you have to re-register like every…

Woman 2: Every 2 years I think.

Woman 3: Yes and they go...

Woman 4: No they don’t tell you, because I thought that I was on a list for about 15 years, but it turns out I wasn’t, they cancelled it ages ago, so yes, no they don’t tell you.

Woman 3: So if you have a big waiting time, you haven’t re-registered, you have lost all of your waiting time.

The challenges of accessing social housing have been acknowledged in all the previous waves of MIS research. Perceptions of the precarity and condition of the private rental sector added a new perspective to the discussion this year. They are reflected in analysis from the charity Shelter, showing that no-fault evictions reached an all-time high in 2023 (Shelter, 2024a) and that there was an overall loss of 11,700 social rent homes in 2022–23 (Shelter, 2024b). In addition, the English Housing Survey’s figures from 2021 show that 23% of private rentals did not meet the Decent Homes Standard, compared with 13% of owner-occupied and 10% of social housing (Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, 2022).

Some participants reflected on the difficulties that future generations are likely to face in terms of being able to maintain living standards over time, particularly regarding housing.

Research transcript - parents, Sheffield:

Man 1: I mean I have already told my kids, I think we have got quite a nice house, the kids like it and I have always said to them, I said: ‘You need to get used to the idea you’re not going be able to live in a house like this’ … You know, just about in terms of what is, you know, almost acceptable, I think living standards are going the other way now aren’t they? And I’m not trying to disappoint them, but I am just sort of trying to be pragmatic about what they should expect.

Man 2: We have had that, my mother-in-law, we have had to sell her house to pay for her care, so that for them, you know, actually maybe the kids could have any money from that, but that is gone.

Parents agreed that children should have safe outside space to play in, so they said that a house with a small garden would offer suitable accommodation, rather than a flat. They said that a 2-bedroom house would be adequate for lone or partnered parents with one child, and that families with 2, 3 or 4 children would be able to manage with 3 bedrooms, but that these needed to be of a ‘decent’ size. There were several accounts of older children being ‘squeezed’ into bedrooms that were too small because of the combination of ages and genders among siblings.

Research transcript - parents, Sheffield:

Man 1: No I think you definitely need outdoor… well personally I think you need outdoor space because like I say if we go back to Covid, we were really lucky in that our garden is not big but at least we had got an outdoor space that our kids could go out into. Now if we were in a flat, kids like back then would have been 10/11 or 11 and 12. Now having kids just cooped up in a flat, that would have been a nightmare and there will have been people… there will have been people in that situation. I would have hated to have been in that.

Woman 1: I have been in flats and high rises with mine, on the 6th floor with a lift that doesn’t work and a twin pram, and shopping, sometimes the main door downstairs doesn’t work, the communal area downstairs is not socially acceptable for children to play in because it is used by drug users and alcoholics. [On] the stairs there is a lot of young people on that are smoking and drinking because there is no youth clubs for them to go to, so it is not nice. My kids would often come to me and like I am scared, and I am like: ‘It is fine, it is fine, they are just doing their own thing’… You know, I was used to it because I grew up in that area erm, but I would definitely say… I am in a house now and I have got a garden, it is not massive, but it made the world of difference to everybody’s like mental health I think. Rather than being like cooped up in a flat.

Man 2: Granted there are a lot of parks and that, but I think if you have got that outdoors space immediately outside of your house then it makes it far better for parents. Like if we weren’t parents then I suppose if we were in a flat then we might have managed a little bit better but that is why we needed it, mainly for the kids.

Woman 2: Can you imagine them taking them to a park or thinking ‘Oh god I need to take my kids to a park’ to have that little outside space, every day that has to become part of your daily task along with everything else. Like it’s, you know, it becomes more of a chore than something that is enjoyable for you all to do. Well, from a parent’s perspective I think.

Working-age adults without children said that a one-bedroom flat would be adequate for either a single adult or a couple without children. Flats would be rented from a private landlord because this demographic group would be very unlikely to be eligible for social housing unless they had complex additional needs. In previous years, groups said that unfurnished private rented accommodation would include flooring, curtain poles or rails, a cooker, a fridge freezer and a washing machine as a standard package. In 2024 they said that only the flooring, cooker and curtain poles were likely to be included in lower-cost rental flats, so tenants would be expected to provide their own fridge freezer and washing machine. Private rents rose by 8.9% in the 12 months to April 2024 (Office for National Statistics, 2024b), so it is possible that lower-rent properties now offer fewer amenities as standard than before.

Research transcript - single working-age women without children, Newcastle:

Woman 1: It is very unlikely, very rare, to find furnished places now. Or they put the rent up quite a bit just to cover the cost of if the fridge or anything broke, so 9 times out of 10 I would say people don’t have furnished places already.

Woman 2: So like they don’t have an oven and stuff.

Researcher: So you’re talking about the white goods as well, so the fridge freezer and the…

Woman 2: Yes.

Woman 1: So like when I moved in, I didn’t have anything, I had to get it all.

Woman 3: The cooker might be there because it is integrated – they don’t take them out.

Woman 4: I rent, and I had all of that, it was unfurnished, but the kitchen was covered so I guess it just… it does depend.

Woman 3: Depends on the landlord I think doesn’t it?

Woman 4: It is 50/50 it just depends on who she [the case study under discussion] rented off because obviously some have, some haven’t so…

Woman 2: I think given the prices of things going up at the minute I would calculate that she would need to buy them herself.

Woman 3: I have moved 3 times and every time I have had to get my own white goods. The only thing that has been included I would say is an oven every time but that is because they are either built in or it is just a really old oven.

Researcher: OK so would it be reasonable for us to kind of build in that [the] cooker or oven would be there, but she would have to get the rest of the white goods?

Woman 3: Yes.

The groups of retired people also talked about the precarity of private renting and the difficulty of moving from a private tenancy to social housing, again because of a lack of availability of appropriately sized accommodation. They agreed that a one-bedroom flat would meet the minimum needs of a single pensioner and that a 2-bedroom flat would be needed by a couple, despite the fact that if the case study pensioners were to become in need of social housing now (rather than in the past) they would be likely to be allocated only one-bedroom accommodation, which groups considered to be less than adequate.

Research transcript - partnered pensioners, Manchester:

Man 1: We live in a rented property and 18 months ago, we had been renting a property for 12-and-a-half years and she wanted us out, she was going to sell it, blah, blah, blah, went down the route of trying to get erm… a council house or a council flat, 2 bedroom, no way on god’s green earth were we going to get a 2-bedroomed, even though every weekend we have grandchildren stay. There is no way they won’t give us a 2-bedroom flat or a 2-bedroom house. That is a fact.

Researcher: Is that because there aren’t very many of them or because they… would they give you a one-bedroom rather than a 2-bedroom?

Man 1: It is one bedroom and the one-bedroom flat that they were trying to give us, I wouldn’t have put a dog in it.

Researcher: The reason that 2 bedrooms is there is because when groups were kind of thinking about what erm John and Mavis [the retired couple case studies] needed, they said as you get older… that bedroom is there if one of you is, you know, coughing a lot in the night, the other one can go and sleep in a different room. Having that space when there is 2 of you in a flat, as a minimum, groups said that was a reasonable expectation. What we’re hearing increasingly is that even though that is a reasonable expectation, it doesn’t actually exist in lots of places. And it varies wildly across the country… So the fact that you can’t access 2-bedroom flats or that certain housing is incredibly difficult to get… people are on lists for years and years and years to access social housing. This part of this work kind of helps to inform thinking about that. Does that make sense?

Man 2: We’re saying what we should [be able to access] or require and you’re saying the Government can’t do that or won’t do that so what we would like to say is: ‘This is what we would like, but this is what we can’t get.’

Decorating, maintenance and insurance

All groups included a modest annual amount to cover minor repairs and provide a resource to maintain their rental property to a satisfactory standard, for example by repainting a room occasionally. Parents also included a small amount of equipment and an annual budget to be able to keep the garden tidy and repair or replace fencing occasionally, as this is tenants’ responsibility in social housing. All household budgets include the cost of contents insurance with cover for accidental damage, calculated using quotes from price comparison websites.

Table 4 summarises the housing specifications for each household type. All accommodation is assumed to have gas central heating.

| Household type | Accommodation |

|---|---|

| Single pensioner | 1-bed flat, social housing |

| Couple pensioner | 2-bed flat, social housing |

| Single working-age adult | 1-bed flat, private rented sector |

| Couple working-age adult | 1-bed flat, private rented sector |

| Lone/couple parent plus one child | 2-bed house, social housing |

| Lone/couple parent plus 2 children | 3-bed house, social housing |

| Lone/couple parent plus 3 children | 3-bed house, social housing |

| Couple parent plus 4 children | 3-bed house, social housing |

Domestic fuel

Despite quarterly energy price caps being introduced to mitigate the effects of the dramatic increase in wholesale energy prices since mid-2021, survey data shows that fewer people are using central heating as a main method of heating their home over time. In winter 2021, 78% of UK homes were using gas central heating, with only 3% relying on portable electric heaters. However, gas and electricity prices continued to rise in 2022 and 2023 and the latest data shows a drop to 58% of homes using gas in 2022 and 2023 and a rise to 14% of homes using portable electric heaters as their main heating source by winter 2023 (Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, 2024a). This seems in line with widespread consumer advice to ‘heat the human, not the home’ as a way of keeping domestic fuel bills down (Monro, 2024).

The Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (2024b) estimates that there are 3.17 million households in fuel poverty in England. However, MIS is based on setting a publicly agreed standard of what people should be able to do and how everyone should be able to live, and this includes being able to heat one’s home adequately. Participants were very aware of the rise in gas and electricity costs over time, and discussed the pros and cons of changing behaviours in order to economise on this expense. This included parents debating the inclusion or exclusion of tumble dryers, when the alternative was to rely on the central heating and radiators to air-dry laundry. Working-age adults talked about using air fryers as a more economical way to cook, and pensioners discussed whether or not to include an electric blanket because it was seen as ‘cheaper than putting the heating on’. However, groups agreed that people should be able to afford to use their heating to keep warm, and based on this premise, said that additional items such as heaters and electric blankets would not be required.

The homes in the MIS budget calculations are assumed to have gas central heating as this remains the prevalent means of heating homes in the urban UK. MIS domestic fuel budgets are calculated by a home energy expert, based on indicative housing plans and with the heating set at a level that would maintain the fabric of the property as well as the health of the occupants. Leaving some rooms unheated during cold weather can lead to problems with damp and mould (Centre for Sustainable Energy, 2022), which in turn can have a negative effect on people’s mental and physical health (Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities et al., 2023). The fuel element of the budget therefore reflects the cost of sustaining a level of consumption based on meeting needs, rather than on price. Chapter 6 shows what proportion of household budgets comprises domestic energy costs and how that has changed since 2023.

Food and drink

To develop the food budgets for different households, groups are asked to decide what meals, snacks and drinks households would consume at home, and then these specifications are used by a nutritionist to compile weekly menus and required ingredients. At this stage, the nutritionist also suggests foods to add in or change so that the food budget reflects a diet which is in line with healthy eating guidelines. The nutritionist’s suggestions are taken to further stages of groups to check that they are reasonable.

A typical day’s food includes:

- 3 meals a day (breakfast, a light lunch and a substantial dinner)

- one or two snacks (in the morning and/or afternoon)

- drinks such as water, cordial, fruit juice, tea and coffee

- a modest amount of alcohol for adults.

The list above applies to food eaten regularly at home. Eating out, takeaways and food for festive celebrations are covered in the section on ‘social and cultural participation’ below. Within the weekly menus, groups specified a mix of meals made from scratch, some using ready-made sauces and a few pre-prepared items for convenience. For households with more than one member, the nutritionist creates a combined menu based largely on her original ones and allowing some variation, especially in relation to breakfast and weekday lunches where children, parents and working-age adults are all more likely to be out of the home and eating separately from other household members.

We price the resulting food baskets, compiled from all of the week’s ingredients and food and non-alcoholic drink items for:

- working-age adults (singles and couples)

- pensioners (singles and couples)

- partnered parents plus toddler

- partnered parents plus preschool and primary school aged children

- partnered parents plus preschool, primary school and secondary school aged children

- partnered parents plus toddler, preschool, primary school and secondary school aged children

- lone parent plus toddler

- lone parent plus preschool and primary school aged children

- lone parent plus preschool, primary school and secondary school aged children.

In 2022, we revised the method used to construct the food basket for the households without children, to take into account that the UK population as a whole has increased in weight since the first iteration of MIS research published in 2008. Our analysis compared the average weight and height of both men and women using more up-to-date values, and assumed moderate activity and exercise levels. This is more reflective of current societal norms and requirements.

Groups discuss whether the food should be priced all at one shop or at a range of different retailers. Some budget retailers (particularly Aldi and Lidl) are widely perceived as being cheaper than the main supermarket chains (Asda, Sainsbury and Tesco), although the latter all price-match with competitors, including the budget retailers. However, groups agree that Aldi and Lidl’s product ranges are not as extensive as those of the major supermarkets, which can mean going to other shops for particular items and ingredients, which has a time cost. Cheaper supermarkets can often be harder to access in some urban locations, as they are often on the outskirts of a town and may be difficult to reach by public transport.

So far, groups have agreed that we should continue to price the whole list in Tesco so that people can buy it all under one roof if they choose to. Consensus is that we should use prices mostly from the supermarket’s own or generic brand, but not the ‘basic’ or ‘no frills’ range. This and the inclusion of a few branded items (usually because of special offers at the time of pricing, or because the pack size means less wastage in terms of the quantity required) mean that there is flexibility in the budget to upgrade some things and economise on others. People would have the option of making their budget go further by buying more from the budget stores and only a few things from Tesco, and/or downgrading the quality of some items in order to upgrade others (usually better-quality meat is mentioned in this context) using the money saved. We include discounted Clubcard prices where appropriate (Tesco Clubcard is free to join and offers price reductions on a range of items each week) to reflect realistic shopping behaviours.

Clothing

The types of clothing and footwear that groups listed were similar to those in previous MIS reports. They identified the need for a range of shoes and clothing for everyday wear, special occasions and sports activities, as well as school uniform for school aged children (see below). As in previous years, groups specified that the majority of clothing and footwear for all households could come from relatively cheap high-street retailers, with some exceptions. For example, they included a pair of Clark’s shoes for each child to provide good foot support as they grow, and similarly each adult had a pair of good-quality ankle or walking boots. The frequency of replacement reflected item quality. For example, groups said that all adults’ t-shirts could come from the supermarket, but would be replaced every one to 2 years. Meanwhile, adults’ thick winter coats, which tended to be specified as better quality, tended to have a replacement rate of every 3 or 5 years. Children’s clothing mostly needed to be replaced yearly, to take into account the rate at which they grow.

For children, groups included everyday and special-occasion clothing, summer and winter wear as well as fancy-dress costumes for very young children. In addition, groups included school uniform for primary and secondary school aged children. Groups in MIS research have always included a mix of branded uniform items from school stockists and unbranded items from the supermarket, with secondary school children typically needing more branded items than primary school children. Statutory changes in 2021 called for schools to reduce the number of unnecessary branded items required in their uniform policies, to decrease costs for families (Department for Education, 2021). While the guidance is legally binding for all state schools, what counts as a reasonable or necessary quantity of branded items is open to interpretation, and guidance has been followed with varying success (Thomas, 2023; Walker, 2023).

For primary school aged children, although groups said that the number of branded items varied from school to school, they agreed that the number required had reduced overall. For example, in 2020, groups said that primary school children needed 3 branded school jumpers from a uniform stockist, whereas in 2024, groups said that only one would be needed from the stockist, with the remaining 2 plain and priced at the supermarket. Similarly, groups in 2020 included 2 of 5 polo shirts from the school stockist, while the 2024 groups said that all polo shirts could be plain. Groups agreed that a branded school jumper was still needed as schools may still stipulate that children wear such an item to take part in activities such as school trips or photographs.

Meanwhile, the number of branded items that secondary schools expect their pupils to wear remains higher than at primary school. In comparison to 2020, groups in 2024 included the same branded uniform items, including jumpers, blazers and school ties, and added school-branded physical education (PE) items. Groups also talked about the limited support with uniform costs, noting that while secondary school students typically need to wear many more branded items, there were fewer schemes available, such as second-hand uniform swaps, in comparison with those in primary schools.

Research transcript - parents of secondary school children, Leicester:

Researcher: Is there anything else on there that you think needs to come from the school stockist?

Woman 1: All the PE kit does at our school.

Man 1: Yes.

Woman 2: Yes, they have got to have the logo on.

Woman 1: They don’t help you, do they?

Woman 2: I think in primary school, the PE, the jumpers, the t-shirts, you give back to the school and then you have… a day of second-hand uniforms, but in senior school that doesn’t happen.

While secondary school uniforms have historically cost more than primary school uniforms, group discussions suggested a widening gap between the 2 school stages. Families with children attending primary school in 2024 can keep costs lower than in 2020, purchasing most uniform items from supermarkets, while the proportion of branded uniform items for secondary school children has remained high.

Household goods

Items in this category include:

- furniture

- flooring (for those in social housing)

- soft furnishings

- appliances

- small electrical items

- cookware, kitchenware, crockery and cutlery

- cleaning and laundry supplies

- children-specific items (for example, stair gates, highchairs and baby monitors).

Many of the items in the list of household goods have remained the same over time, with groups in 2024 suggesting similar types of items, retailers and rationales for their inclusion to those suggested in previous MIS research. Some of the household goods in MIS serve a practical purpose, such as providing storage or the means to prepare and serve food. Some specifications for household goods were about achieving physical wellbeing and comfort. For example, groups said that people need a good-quality mattress to ensure a good night’s sleep. Similarly, blankets were included in the living area and bedrooms for cosiness. In other cases, household goods were specified partly for social participation. The types of seating in the dining and living areas, and the quantities of crockery, cutlery and glasses, for example, were intended to enable households to have enough for themselves and some guests, while a budget for enabling a household to put their personal stamp on their home acknowledged the importance of making a space feel homely.

Housing tenure also influenced household goods. For pensioner households and households with children, groups specified that tenants in social housing would need to provide flooring themselves, while working-age adults without children would not need to factor this in as it would be supplied in the private rental sector by landlords. A change in this year of MIS research was that groups said that fewer white goods were provided in the private rental sector, indicating that working-age households without children would need to buy their own fridge freezer and washing machine. Groups said that cookers were more likely to be provided in private rental properties because they were more likely to be a kitchen fixture. All groups agreed that a dishwasher was not an essential item, so did not include it.

Groups considered the energy efficiency of some household items, particularly kitchen appliances, in different ways. Groups of pension-age households specified that the energy efficiency of the cooker, fridge freezer and washing machine should not be below a B energy rating. Groups of working-age households with and without children did not specify a high energy rating for those appliances.

Groups specified that all households should have airers for drying laundry. Parent groups discussed the needs of different household sizes and how much washing could be dried on radiators.

Research transcript - parents, Derby:

Woman 1: It is a time… for me it is a time thing as well, I mean I have got 3 kids, but it is also… I would love to have the time to erm you know wait for stuff to dry and all the rest of it, I just need to get those jobs done, kind of thing, so it gets out of the washing machine into the dryer and move things along like the factory that is the household kind of thing around the house.

Woman 2: Yes I have got a spare room that was an office, now is a laundry room, it is that that is where everything goes because otherwise it would be in the living room, it would be in the kitchen, it would be in the bedrooms, it is just not big… we don’t have a big-enough space for that.

Woman 3: I do wonder as well, if we’re talking about this, maybe this sort of household, you know, especially if you’re limited on space, drying stuff on dryers, I do think the health thing – because it says they are in a reasonably good state of health, you know, and I do think all of that indoor drying… We see it with tenants, I mean the moisture it creates erm and that is, you know, health-wise, in the long term I don’t think that is good for… especially if there is children, so I think the dryer has multiple benefits.

Eventually, the consensus was that households with 3 or more children would need a tumble dryer, which is the same as groups have decided since 2008. In 2024, for the first time, groups also discussed whether it was better to include a more expensive but energy-efficient heat-pump dryer or a cheaper condenser dryer with higher running costs. They concluded that it would be preferable to include the heat-pump dryer to maximise energy efficiency.

Meanwhile, working-age households without children and pension-age households included a small air fryer as this was considered an energy-efficient way to cook meals. The parents’ groups also discussed air fryers but concluded that they might not be adequate for larger households.

As in previous years of MIS research, groups said that most household goods could come from relatively inexpensive retailers, such as supermarkets, Argos, B&M and The Range. Pensioners sometimes specified higher-quality goods, but with longer lifetimes than those that other groups specified. They said that older people need sturdy furniture items that can be delivered already assembled. All groups said that items such as beds and sofas should come from retailers where consumers can try them in-store before they buy them. Therefore, these items were costed at retailers such as DFS, Dreams and IKEA. Parents have typically been the only groups in MIS research to include items from IKEA, as the only household type in MIS with a car. However, with the reduction in delivery costs charged by this retailer, now also factored into some households’ budgets for deliveries other groups said this would be a reasonable option.

Household services

Items in this category include:

- phones

- broadband

- postage and deliveries

- babysitting

- childcare.

Groups agreed that each adult and secondary school child needed an inexpensive mobile phone, in keeping with the consensus from previous years. However, this year there was more detailed discussion of the capabilities of a ‘basic’ smartphone to meet their minimum requirements. Groups talked about needing phones for email, online banking, shopping, paying bills, ordering repeat prescriptions, finding information, engaging with official agencies, applying for jobs, taking photos, connecting with friends and family and accessing entertainment. While still a long way from the most expensive models, it was clear that the very cheapest smartphone handsets would not suffice for this level of functionality. Participants noted that some mobile apps were now far more demanding of both storage capacity and processing speeds, and gave examples of where the cheapest smartphones had not been adequate.

Research transcript - lone parents, Edinburgh:

Woman: It doesn’t work, so my dad had that phone and ended up having to keep on installing an app… uninstalling something he wasn’t using to be able to use one that he was and switch the apps… And then he gave that to my daughter when she was 11, so she was only really using Duolingo and like a couple of games and very quickly didn’t have enough storage on it to be able to use like 2 or 3 apps.

Research transcript - partnered fathers, Birmingham:

Man: So I would say you have got to go over an entry [level phone], because most of the entry-level Androids nowadays can’t run half the apps.

Researcher: Right.

Man: I know that because mine broke and I had to go and buy one to temporarily make calls and I couldn’t install my email, I couldn’t install various stuff because it didn’t have enough memory.

The mobile phone that groups included was priced at Tesco Mobile for all groups, through 2-year contracts that include unlimited calls and texts as well as the phone handset itself. Groups discussing the needs of secondary school children, pensioners and working-age adults without children opted for a Motorola smartphone that was one up from the cheapest monthly prices that Tesco Mobile offered. Parent groups described particularly heavy usage requirements, because of also needing specific apps to liaise with their children’s schools about homework, school dinners, clubs, activities, meetings and other arrangements; consequently, the parents settled on a slightly higher-spec phone (also Motorola), which was the cheapest from Tesco Mobile with 128 gigabytes (GB) of storage and 4GB of random-access memory (RAM). Parents included a sturdy phone case and a screen protector for secondary school children’s phones to help protect them from accidental damage.

All groups specified a need for broadband internet at home and agreed that the majority of internet data consumption would use Wi-Fi connections, to minimise additional costs. Pensioner groups said that the Tesco Mobile phone contract’s default 500 megabytes (MB) of data a month provided an adequate level as a minimum for pensioners. For parents and secondary school children the minimum was 3GB of data a month. Parents agreed that learning to manage a limited amount of data was an important skill for children to develop. Working-age adults without children agreed that a 6GB data package would be suitable to ensure that people could use their phones as required when out and about.

Landline phones were not considered necessary by the parents or working-age adults without children, although pension-age groups continued to include a landline service and pair of landline phone handsets as a back-up option in case their mobile phone was lost, broken or out of battery, or to provide handsets with larger buttons. Participants were aware that traditional landline technology will soon be fully replaced by internet-based digital voice systems, but this had not been rolled out universally at the time the fieldwork was conducted.

Budgets for postage and deliveries were included for all household types, with differing emphases on online shopping (where free delivery may not always be available and return costs are sometimes incurred) and sending cards and presents.

Babysitting

Parent groups allocated budgets for babysitting, so that they could spend some time together or take part in activities outside the home without their children. The expected frequency of using a babysitter varied widely between participants, but partnered parents agreed on a minimum of £20 every 2 months. This set-up assumed an informal arrangement such as buying a takeaway pizza for the babysitter, with a reciprocal deal through which one of the parents would in turn babysit for their sitter’s children on another occasion. The groups said that the partnered parents could alternatively choose to spend this money on a more expensive babysitting service that they would use less often, or put it towards a special ‘date night’ meal at home while the children were in bed.

As in previous years, babysitting was a particularly significant need for lone parents, who noted that reciprocity can be more difficult for a single parent with sole responsibility for their own children, and that they would not have the option of going out alone while a partner looked after the children. To accommodate people without a suitable network of informal support in place, the lone parents included an amount for a member of staff from a nursery or agency to babysit for 2 or 3 hours once a fortnight.

Childcare

Parent groups also discussed childcare, acknowledging that help from relatives or friends was not available to everyone, and agreeing that nurseries were the necessary minimum to budget for to allow parents of toddlers and preschool children to work – while still providing the choice of a childminder (usually at a cheaper rate) if they preferred. This has been the consensus in MIS budgets for families with young children since 2016. After the disruption caused by the pandemic, participants said that nurseries would be a more reliable source of care, rather than potentially depending on a single childminder and their child(ren) remaining in good health.

Research transcript - parents, Sheffield:

Man 1: Our kid’s in a nursery, which was unfortunately… sort of forced to do that, but I know childminders, they struggled a bit more because… they are providing childcare, and they are poorly, or their kids are poorly, there is no childcare – and then you’re stuck, aren’t you then? So that was sort of one of the reasons why we didn’t go down that route, but I suppose we were fortunate, we had that choice that we weren’t bound so much by going for the cheapest option…

Researcher: So there are different options, it doesn’t mean everyone has got choices because of income. But again, thinking about where we set the standard rather than what people can afford, should we set the standard at the childminder level… or should we set it at the nursery level?

Woman 1: Nursery.

Woman 2: Nursery level, yes.

Researcher: Right, so why is that?

Man 1: I think like we were just saying just now, where the fact obviously, childminder, only takes them to go down with Covid, that is them out of action for 5 days you know or whatever it is… whereas in a nursery, there is always that back-up if someone is sick, they have usually got some sort of…

Researcher: So you have got a bit more reliability, yes?

Man 1: It doesn’t have to be a week of Covid, it can just be one day of D and V [diarrhoea and vomiting] and that can just throw your week out.

Full-time nursery provision 5 days a week was considered essential because of the need to allow for full-time work. Assuming a 9am to 5pm working day, this meant childcare between 8am and 6pm to build in time for travelling to work and possibly dropping off other children at a school elsewhere. Groups said childcare would be needed for 50 weeks of the year, with the remaining 2 weeks being accounted for by bank holidays and closure over the Christmas period. Groups in England said that the existing scheme providing 15 hours of free childcare a week (for 38 weeks of the year) for 3- to 4-year-olds was widely available, but there was more uncertainty about the availability of 30 hours of free provision for these children (when eligible), as well as the expanded versions of the ‘free hours’ childcare subsidy scheme that are scheduled to start in September 2024 and September 2025.

For primary school children, the childcare budgets include breakfast clubs and after-school clubs during school terms, again to allow for parents to work full-time. Outside of term-time, the groups expected the parents to use their annual leave to look after their children as much as they could. Assuming 4 weeks’ leave a year per parent, this left a remaining 9 out of 13 non-term weeks when a single parent would have to use holiday clubs for primary school children, and an equivalent 7 out of 13 non-term weeks of primary school holiday clubs for partnered parents if they took one week of leave at the same time as each other for a family holiday.

Groups did not think that potential flexibility for working from home post-Covid was widespread or significant enough to have an impact on these childcare requirements. Groups also acknowledged that for some workers it can be difficult for parents to take time off work during school holidays, depending on their job and the leave requests of colleagues. There was no budget for childcare for secondary school children, but groups agreed that they would need some extra money to entertain themselves during school holidays (this is included in their leisure budget).

Health and personal care

Items in this category include:

- toiletries (soap, toothpaste, shampoo and so on)

- hairdressing costs

- home healthcare (for example, paracetamol, ibuprofen and hay fever tablets)

- prescription costs

- dentistry

- opticians

- other health costs.

Groups listed the types of toiletries and personal items usually included in MIS, such as shampoo, shower gel and sun cream. A notable change this time was that participants added personal items for working-age men without children that have previously only been included for working-age women, such as a monthly cosmetics budget, hair bobbles, hair clips and makeup remover.

Research transcript - single working-age adults without children, Cardiff:

Man: I think everything should be included [for men] because there are some guys who [wear] nail polish, some guys who have long hair will use dry shampoo, they will use hair bobbles, use hairbrushes and use hair clips.

Woman: I feel like it is hard to genderise toiletries.

Groups also aimed to be more inclusive with the budgets for hairdressing and haircare costs, to acknowledge a diversity of hair needs. Groups said that people with different hair types and textures, for example hair that is very curly, wavy or coily, may need to visit hair salons more frequently, they often have difficulty finding suitably qualified stylists and they pay more for hairdressing services and hair care products.

Research transcript - parents, Manchester:

Woman: It… adds up… It is not the same price for me to just… I can’t go to any hairdresser and say: ‘Oh can you do my hair?’ It is like 3 times as much for us… As a black woman, I never sat down with my mum or whatever so I don’t know how to look after my hair, so I have to rely on somebody else to try and help me look after it… not everyone has them skills, so they do have to go to a salon to maintain it… I can’t just scrape it up… I have to have some sort of product.

To reflect a diversity of haircare needs, groups decided on a budget per person that would mean that working-age adults and school-age children could visit a hairdresser monthly, and could cover a broader range of styles, such as braiding of people’s natural hair. A budget for preschool children also included a hairdressing visit, but less frequently, while groups said that toddlers did not need to visit the hairdressers. Groups included amounts to allow for the use of additional haircare products. Pensioners included enough in the budget to cover regular trims at a salon offering concessions and a home box dye for pension-age women. Primary school aged children had head-lice treatments and a nit comb added.

All groups said that accessing healthcare appointments was challenging. For example, they described the difficulty of getting an appointment with NHS dentists, an issue that has developed over almost 2 decades but grown exponentially since the Covid-19 pandemic (Green et al., 2022; Omer, 2023). Despite this, participants included the cost of accessing an NHS dentist so that adults could have regular check-ups, as well as an NHS band 2 treatment every year (covering a filling or extraction), in keeping with previous years of MIS research (dentistry is free for children). Groups added an additional healthcare budget of £200 a year per parent or working-age adult so that they could pay for health-related services (for example, physiotherapy or counselling) if necessary until reaching the top of an NHS waiting list. They acknowledged that it is becoming more difficult to obtain these services via the NHS, and even where it is possible, waiting lists are long.

Research transcript - partnered mothers, Sheffield:

Woman 1: It happens in life, your back goes or your leg goes, or…

Woman 2: That is it. It is for things that the NHS don’t cover, which is a lot now.

Woman 1: Chiropractor doesn’t come under that…

Woman 2: Everybody should be able to budget for that.

Research transcript - lone parents, Norwich:

Woman 1: So I pay for a sports massage for my back, which is triggered from my physio, so the physio was £65, and the sports massage is £36, so that is twice a year if you just have the sports massage, whereas the physio it would just be one trip for the year. But that normally triggers follow-up work is all I am saying, so potentially yes.

Researcher: But is that a need? Because you will have some people who have never been anywhere near a practitioner for any of this stuff, some people who go regularly, some people who have been at some point and accessed it and found it useful but don’t need to go anymore but might again in the future, and so on and so forth. Everybody is different. Does this seem like a reasonable thing to include or is this a ‘nice to have’?

Man 1: A nice to have.

Woman 2: I think the physical is the nice to have, I think the mental [health] is an absolute must have … As in therapy or…

Woman 1: But my physical health impacts my mental health.

Man 1: She [the case study being discussed] is in a reasonably good state of health.

Woman 3: She can still get a bad back.

Woman 1: Jane might be fine; if you look at average numbers, of people in this country or at least families of 2 or 3 people, one of those in that household is going to need the support that is not available.

Woman 2: Let’s say a bare minimum, let’s take counselling for example, that is bare minimum you’re looking at £20 to £25 a session so let’s say once a month because that is all you can afford, it is not a cheap thing to have but… people should be able to have it.

Woman 3: But that is what we’re saying, if we call it say £100, hypothetically speaking, we haven’t analysed that, we are allowing it, we just need to tell them how much we want to allow for this other category. Because Jane may need it for her head, but John [the other case study being discussed] might need it for his back.

Woman 2: OK, then I would say £250 a year.

Woman 4: Are those things that you can access via your GP? For instance…

Woman 2: They are, yes.

Man 1: Yes. Yes I know it is not there…

Woman 4: But you could. Go on a waiting list or something.

Woman 3: And [risk] making it worse as you go along.

Woman 4: And you can say the same about a dentist or an optician, or do you know what I mean? If we look at it like that…

Researcher: So this is a sort of routine maintenance for Jane that isn’t covered by these other things. OK? And so what has changed? Why … why now, why in 2023, almost 24 is this something that is coming in for the first time? Because we have not seen this before, why is that?

Woman 3: Waiting lists.

Man 2: I am trying not to be biased because I am in that field, but you have hit the nail on the head in that it is about the waiting lists. I think they should have something complementary or maybe to fill that void because I think you can get it on a health service for free so… you should be expected to wait to a degree, if you can’t wait you should pay for it.

Woman 2: You have got that ability.

Man 1: But a years’ worth is expensive as it is a lot of money, so it is going to cost about that so… is it more about somewhere in the middle? Some top-up complementary stuff, which is kind of wellbeing…

Woman 4: Because there are other…

Man 1: Can still be expensive but it is probably cheaper then…

Woman 5: Because you could download an app for example, I know… you know there is mindfulness and things like that that is potentially £20 a month, which covers that, so there are other avenues…

Researcher: How you use that resource is entirely up to you and not everybody needs it, what we can’t do is meet everybody’s needs. This is a benchmark we don’t want anyone to fall below but we’re not saying it can meet everyone’s needs, and it might be that some years, again, she needs a lot of help or a lot of visits and some years she doesn’t need any and that will come and go.

Woman 2: Or she might have 3 a month and not for 6 months.

Woman 1: A lot more than…

Woman 3: Maybe £150.

Woman 1: So £150 to £200 a year.

Researcher: So, just to be clear, this is about access and waiting lists and recognition that not everybody can… I was going to say can afford to wait but there are some problems that are too urgent for them to wait.

Woman 2: That is where it is tricky though because an urgent mental health crisis gives you the crisis team… they will go to you ‘OK these are the people that can help you’ and they will give you that care, until they deem you as not a risk, so therefore you are potentially getting that service at your worst… they have then gone ‘OK we have done your risk, we have done this, bugger off now and deal with it yourself’ and then it is not a good state, so it is having that money in the bank to deal with that at the end of it to cover that shortfall.

Man 2: I can see where the £200 is coming from. Because even if you just wanted a massage for a sore shoulder, you’re looking at £60, you’re not looking at… so £100 over a year is nothing so I think £200 as a lump sum, might sound a lot but it is around about the right figure. If you want to use that for whatever you want to for mental health, for a sore leg, for a sore back, that will most probably get you the treatment you need to deal with it.

Woman 2: But that is less than £20 a month really.

Woman 3: Which is not a lot.

Man 2: I think one more thing then is there are waiting lists and I think it is harder to be resilient because of lots of other factors like climate, cost of living crisis. All the things that add to a wellbeing need.

These are just some examples of treatments that an individual may now need to self-fund due to the declining number of NHS-covered services in the UK (Exworthy et al., 2023). Meanwhile other services that are covered by the NHS have significant, and growing, waiting lists, as already alluded to. Waiting lists for NHS physiotherapy, for example, have increased by 27% since January 2023, comprising a total of 323,965 people (Tapper, 2024). Evidence of the rising prevalence of medical self-funding can be found in the burgeoning availability of payment plans and loans for treatments (Gabert-Doyon and Quinio, 2024). Drawing on their personal experiences, groups considered the inclusion of the healthcare budget for some self-funded services vital for wellbeing.

Research transcript - working-age adults without children, Norwich:

Man: Whether it is mental or physical, you need to be able to have the choice to not go with the NHS and see yourself on a waiting list for years and years. You want to just be able to get the help that you need as soon as possible. So, you need the little budget to put towards that.

[…]

Woman 1: Physical, mental [poor health], it can potentially, for example, stop you from working … So if you need to get back to work and you need some sessions on your back to get you there, then you have got to do that if it is necessary.

Woman 2: I think the key thing is [participation] in society … that sort of thing prevents you doing your clubs or socialising, having that human connection, kind of mental side … Actually, I think it is a need to participate in society.

[…]

Man: The waiting lists are getting much longer as well, so we need a budget that can last you until you can reach the top of the waiting list.

As in previous years, pensioners included a budget for podiatry so that older people could access help with taking care of their feet. Groups also included the cost of prescriptions for working-age adults (these are free for pensioners and children) and over-the-counter medicines such as paracetamol, plasters, antihistamines, thermometers and cold remedies.

Eye tests at a high-street optician chain every 2 years were included for working-age adults (these are free for children and pensioners) along with a budget for glasses so that working-age adults and pensioners could have some choice of frames and lenses (for example, varifocals). Groups said that the choice of glasses available through the NHS was adequate to meet the needs of children.

Transport and travel

Transport budgets for households with children include one second-hand car per household, to allow families to meet their needs for travel to work, school, childcare, appointments, activities and socialising. For urban areas outside of London, this has been the case since 2012, as groups agree that public transport is not sufficiently flexible, affordable or reliable.

Groups included a monthly pass for public transport for each working-age adult without children and one pass between each partnered parent couple, for travelling to work without a car (which the other partnered parent would use). Car ownership was seen as a ‘nice to have’ for households without children, although in the UK a large majority of journeys to work are made by car apart from in London (Department for Transport, 2022). Groups said that people needed sufficient resource to travel as far as the next major town or city, to access a range of work opportunities. This has been the consensus in MIS groups since 2018, reflecting perceived needs for flexibility about where people are prepared to work, which are also evidenced by the commuting patterns of a sizeable proportion of the working population. For example, data from the 2021 census shows that even in pandemic-affected March 2021, almost 5 million people, more than a third of those who regularly travelled to a fixed place of work, travelled a distance of at least 10km, while 1.1 million people travelled 30km or more (Office for National Statistics, 2023).

All groups included budgets for some taxi journeys. Groups of working-age adults and parents discussed using taxis for emergencies, late-night travel and in cases of public transport strikes. The parents’ taxi budgets were lower due to having a car, although the family would still need some additional resource for travelling when their car was being serviced or if it broke down. For pension-age adults, taxi budgets were in addition to free bus (and sometimes tram) travel, but could also be needed for public transport fares during peak times not covered by their bus pass, such as for early morning appointments.

Groups discussing the needs of children allocated money for secondary school children to take the bus to school. One bicycle was included for adult use in each parent household. Parents of secondary school children said that if the child had a bike it would be a present (so would come from the gift budget), but they included associated cycling costs such as a helmet, lights, lock and maintenance for each bike in the household.

The transport budgets also include a budget for visiting friends or family further afield and for the one holiday a year agreed for each household type. These journeys are all included in the car mileage for households with children. Pensioners and working-age adults without children have a budget for rail or coach travel. These groups budgeted considerably more for rail travel than had been the case in 2022, partly due to expectations of being able to visit friends or family more often – but also against a backdrop of significant train fare increases: 5.7% in Great Britain in March 2023 (Office of Rail and Road, 2023), a further 4.9% in England and Wales in March 2024 (Topham, 2024) and 8.7% in Scotland from 1 April 2024 (Transport Scotland, 2023).

Social and cultural participation

The social and cultural participation category is about meeting people’s need to socialise, interact and connect with others, pursue hobbies and interests, maintain wellbeing – mentally, emotionally and physically – and take part in cultural practices and traditions (for example, attending a secondary school prom or exchanging gifts at Christmas). This section is divided into the following subcategories:

- technology for home entertainment and connection

- gifts, celebrations, toys, books, pocket money and charitable donations

- other education and stationery costs

- leisure and recreation

- eating out and takeaways

- holidays and days out.

As in other budget areas, these social and cultural participation needs encompass both specific goods (such as a television) and services (like a holiday package) that can be priced. Other items are allocated a budget that represents an amount that will enable people to exercise choice, for example in how they socialise or spend their leisure time.

Technology for home entertainment and connection

This subsection relates to technology-related needs beyond phone and internet provision, which features among the budgets for household services.

All household types included a smart television (TV). Technological developments mean that a non-smart TV is now far more difficult to find, and 4 years ago in 2020 the smart TV replaced the digital TV with built-in Freeview that had occupied the equivalent role in MIS budgets since 2008. Parents and working-age adults both agreed that a 32-inch screen size would be an acceptable minimum. This remains cheaper than larger models, although there are fewer of them available as screen sizes continue to increase. Pensioner groups specified a 42- or 43-inch screen, as they had done in the 2022 MIS budgets, to make the picture (and subtitles if needed) easier to see. All groups included a TV licence, so that people could watch live TV and BBC iPlayer.

There was much discussion about whether to continue to include an additional TV subscription service, such as Netflix, Disney+ or Amazon Prime, which had been another addition in 2020 (at that time replacing a DVD player). The pensioner households and all families with children opted to keep one entry-level TV subscription in their budgets. However, working-age adults without children decided that this subscription was no longer so necessary now that the constraints of Covid have completely lifted. Working-age participants did note, however, that Netflix had become embedded in modern life:

Research transcript - single working-age men without children, Leicester:

Man: ‘Netflix and chill’ I think got added to the dictionary, didn’t it? Which literally means this… is woven into the cultural fabric, and I think that to participate in society he [the case study under discussion] needs a choice to access that.

Yet the participants also acknowledged that these kinds of streaming services now occupied a less central role in their lives than had been the case when “trapped in” at home during Covid lockdowns. While being clear that MIS is about what people need as a minimum, not what people can afford on a very low income, they said that Netflix was relatively low in their priorities compared with other needs.

Research transcript - working-age adults without children, Sheffield:

Man: I think Netflix for me would be, you know, if I was in that situation where I think – I know it is not relevant to this – but if I think ‘Right, I need to cut costs’, that would be one of the first things I would get rid of.

The compromise reached by working-age adults without children was that the adults could choose to use some of their other budgets for leisure activities or putting a personal stamp on their home to pay for a subscription service, if it was important to them.

It was noted that parents and pensioners were perhaps more likely to still spend more of their evenings at home and thus to rely more on home entertainments such as Netflix, a point that pensioner groups in particular emphasised.

Research transcript - pensioners, Leicester:

Woman: And also Covid has made you like… I mean, I find that I don’t want to socialise as much as I used to before, you seem to have kind of been in your own home for 3 years without kind of having that…

Man: Shut down a bit.

Woman: Yes, shut down, and often me and my husband will choose a movie, and it is just nice to watch a movie together.

Research transcript - pensioners, Birmingham: