Using the Social Housing Green Paper to boost the supply of low-cost rented homes

The Secretary of State promised a wide-ranging review of social housing. This briefing argues the Green Paper must address the 30,000-home annual shortfall to reduce housing costs for low-income families.

Summary

- A step change in delivery of new affordable housing is needed in England. Since 2011, supply has fallen over 180,000 homes short of what is needed. Boosting supply is key to fixing our broken housing market.

- Real income growth among the bottom fifth of the population in recent years is mostly wiped out once housing costs are considered, with consequences for the living standards of those on low incomes.

- Pressures are most acute in London and the South East. Housing Benefit provides some relief, but is expensive for government and no longer insulates households from the broken housing market.

- Improving housing for those on low incomes presents a political opportunity – action is supported by voters across the income distribution.

- More low-cost rented housing lowers housing costs for families and boosts quality and stability by enabling them to move out of the private rented sector.

- Increased supply of low-cost rented housing will also contribute to the Government’s commitment to build one million homes by 2020.

This briefing is intended for use in England. Housing is a devolved matter and separate policy exists in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The step change in delivery needed

Current delivery of affordable housing is falling around 30,000 homes per year short of independently-assessed needs. To fix our broken housing market, there is an urgent need to make a step-change in the delivery of affordable homes.

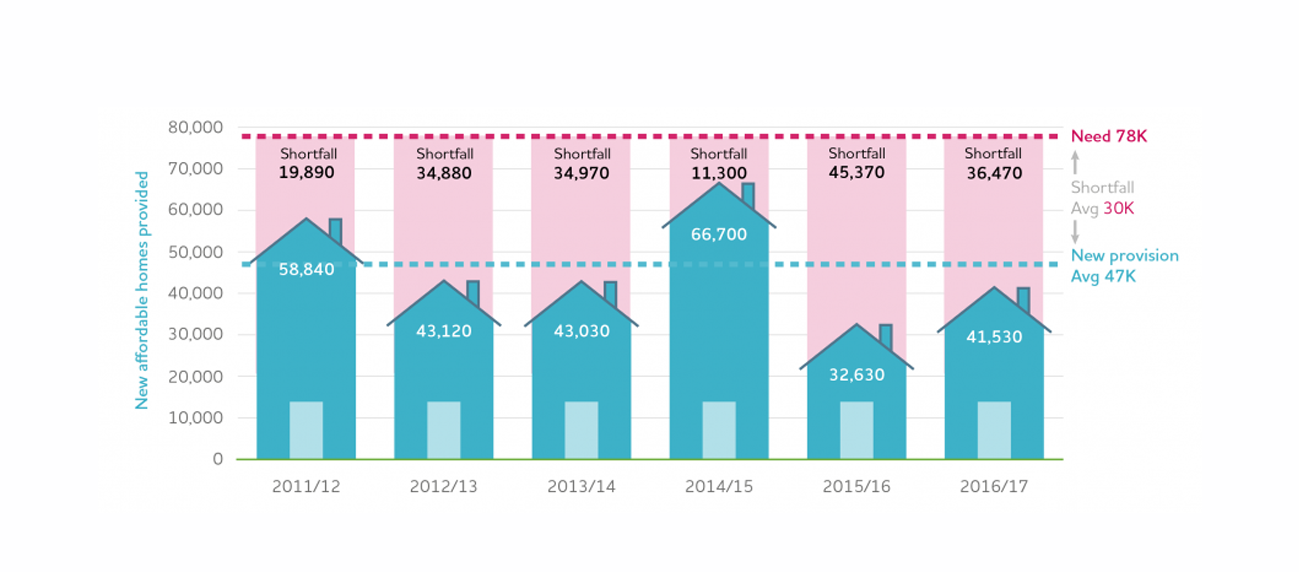

Independent analysis shows that an average of 78,000 additional affordable homes (a mix of low-cost rent and shared ownership) are required in England each year between 2011 and 2031. This level of supply is required to meet newly-arising need and demand.

Delivery has been falling short. On average 47,520 additional affordable homes have been provided in England each year since 2011, leading to a cumulative shortfall of 182,880 homes over the last six years. A step change is needed to boost supply of affordable homes by at least 30,000 more a year. Failure to respond will increase pressure on the housing benefit bill, and result in more people struggling to make ends meet because of their housing costs.

1. The need to accelerate progress

The Government has made some steps in the right direction. For example, the announcement of an additional £2 billion of investment in 2017 focused on areas with the greatest need is a welcome step. However, it is only expected to deliver around 5,000 additional social rented homes each year — just 1/6 of the 30,000 further affordable homes we need each year.

The decision to focus the investment on the areas of greatest need is, however, sensible. Accelerating progress to 30,000 homes per year is key to fixing our broken housing market and improving the living standards of those on low incomes. Failing to do so will see the cumulative shortfall of affordable homes reach 335,000 homes by the end of the current parliament.

The right mix of affordable homes

The independently-assessed need of 78,000 homes per year is for affordable homes of all types — for low-cost rent, and for low-cost homeownership.

Many people aspire to home ownership, and it is understandable that the Government wants to provide pathways for people on low to middling incomes in high-cost areas to achieve that through shared ownership. But this option is still out of reach for many families because of their circumstances. At the point of entering social housing, just 3% of new social tenants could afford even low-cost home ownership options like shared ownership or starter homes instead. These families need low-cost rented housing — that is homes let at social rents, or similar levels, which are affordable to local workers on low earnings.

We do not consider the ‘Affordable Rent’ model, where rents can reach up to 80% of local market rents, to be low-cost rented housing. This model replicates the dysfunction of the local housing market — which is especially problematic in areas of high housing costs, and places significant additional demands on the Housing Benefit bill. It should be noted that the figures for current delivery presented above do include a significant proportion of such ‘Affordable Rent’ homes.

2. The impact of housing costs on low-income families

Boosting the living standards of low-income families requires a dual focus on boosting incomes and reducing the cost of essentials. Actions such as the introduction of the National Living Wage represent some progress on the income front. To reduce low-income households’ largest single cost, housing, the forthcoming Social Housing Green Paper must set out a plan for a step-change in supply of low-cost rented homes.

The impact of housing costs

As the Prime Minister noted in her foreword to last year’s Housing White Paper, high housing costs hurt ordinary working people the most.

JRF analysis shows that real income growth amongst the bottom fifth of households between 2007/08 and 2015/16 is mostly wiped out once housing costs are taken into account.

Pressure from housing costs is increasing: the proportion of people in the poorest fifth of the working-age population who spend more than a third of their income (including Housing Benefit) on housing costs has risen from 39% in 1994/95 to 47% in 2015/16.

In part, this is because in recent years, more low-income families have found themselves living in the private rented sector, where costs are higher. This has a knock-on impact on the Housing Benefit bill.

Acute pressures in London and the South-East

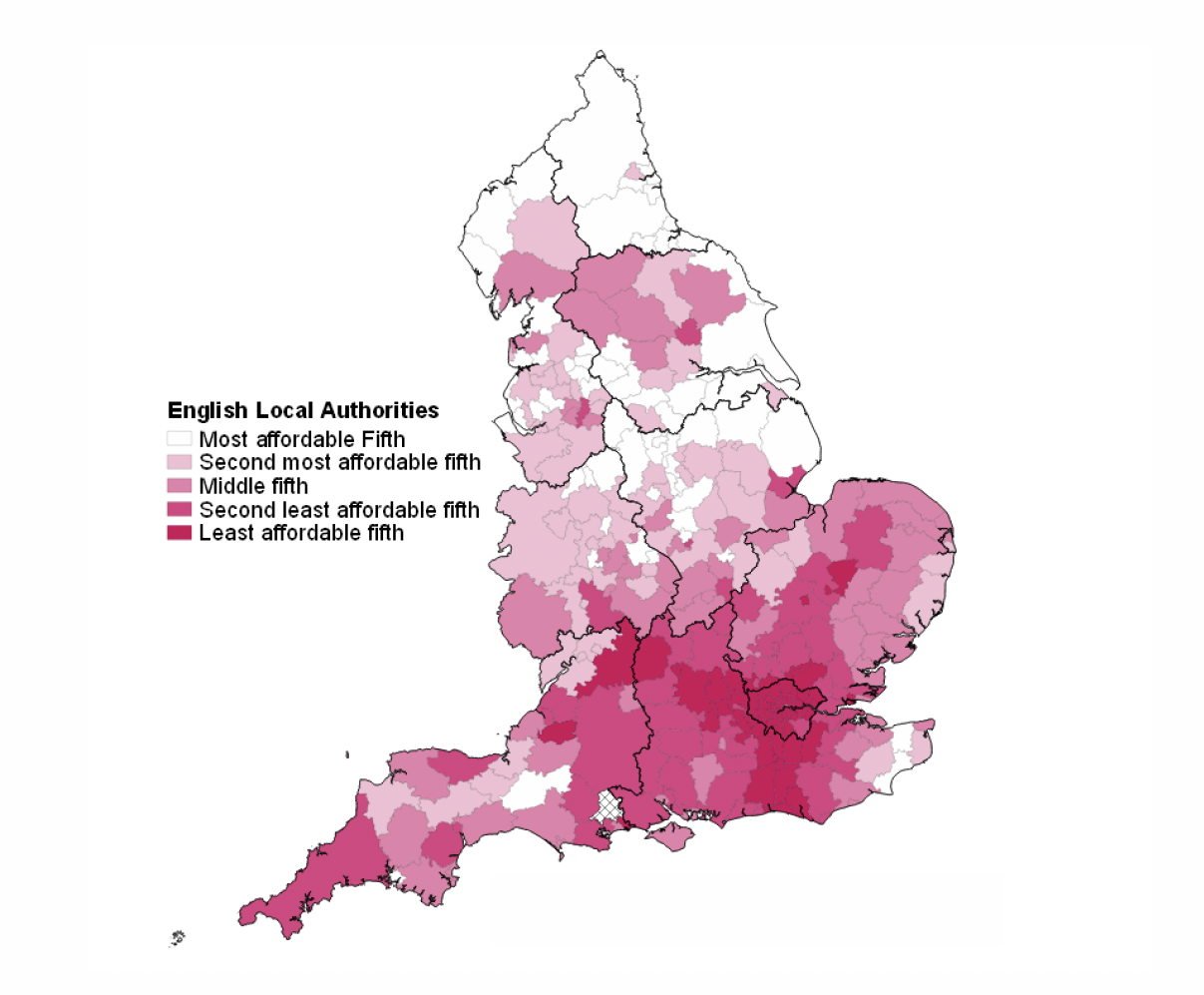

Analysis by JRF of lower quartile earnings and lower quartile private rents across England shows that pressure is particularly acute in London and the South-East, including in districts home to several high profile and marginal constituencies. Monthly rent-to-earnings ratios run at over 40% in much of the south.

These are often the economically vibrant areas where opportunities to enter work — and to progress — are more likely to arise. But buoyant labour markets also fuel higher rents and house prices. To break this cycle, the provision of low-cost rented housing is necessary. Revenue subsidies like Housing Benefit simply respond to these pressures, and are expensive. Capital investment in new homes would insulate low-income families from these pressures for the long term.

The role of Housing Benefit

Housing Benefit plays a vital role in helping low-income families pay the rent, especially in high-cost areas. But this is a costly way to address the problem — in 2016/17 £23.4 billion was spent on Housing Benefit in Great Britain.

It is also increasingly failing to insulate the living standards of low-income private renters from the impact of the broken housing market. Some 90% of low-income private renters face a gap between their income from Housing Benefit, and their rent. They have to make up this difference from their non-Housing Benefit income. On average, 35% of non-housing benefit income is being used in this way by the poorest private renters, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS). The proportion experiencing a shortfall is expected to increase by 2025.

Voters are looking to government for solutions

Addressing the housing crisis facing low-income voters represents a political opportunity. Housing is one of the top concerns of people on low incomes, ranking as a higher priority for this group than work.

The vast majority of the population see providing decent housing for those who cannot afford it as a key responsibility of government. Across all income groups, this responsibility is seen as the third most important priority for government, behind providing healthcare for the sick, and a decent standard of living for the elderly.

The impact of housing on poverty

The cost of housing also drives up poverty. Poverty rates for working-age adults in the UK are 6 percentage points lower before accounting for housing costs. Within England, the impact of housing costs varies by region, and is most acute in London, where poverty rates more than double after accounting for housing costs.

Poverty in the private rented sector has nearly doubled in a decade, and now stands at 4.7 million people, of which 3 million are in working families (2015/16).

With housing costs placing growing pressure on the living standards of low-income families, the current path is not sustainable. It risks tipping those ‘just about managing’ into poverty. There are therefore two options open to government to address the impact of high housing costs on low- income families:

- reverse course on reforms to Housing Benefit, providing immediate relief to families, but with consequent long-term impacts for the Housing Benefit bill

- expand the supply of low-cost rented housing, growing supply of a tenure which insulates low-income families from the dysfunctions in the housing market and can reduce demand for housing benefit over time.

JRF recommends that the Government prioritises an expansion of the supply of low-cost rented housing. The next section of this briefing sets out why this is the right solution.

3. Why low-cost rented housing is the right solution

Low-cost rented housing lowers ongoing housing costs for families and government, achieves higher standards and offers more stability for families. It is popular with tenants. Crucially, it adds additional supply of housing, contributing to the Government’s ambition to get more homes built quickly.

The pressures on families

With earnings not keeping up with prices, most working-age benefits frozen, and the price of other essentials such as food and energy rising, people face impossible choices:

I just couldn't make it work. I had to choose, what do I pay this month, do I pay the rent? Do I pay the electricity? Do I buy some food? And it just snowballed.

Participant, JRF/University of Cambridge study: Poverty, Evictions and Forced Moves

Furthermore, boosting the supply of low-cost rented housing would contribute to the Government’s wider ambitions to fix our broken housing market. The Government is committed to deliver one million homes between 2015 and 2020, plus half a million more by 2022.

Meeting the assessed need for affordable housing would contribute almost one third of the 250,000 homes per year required beyond 2020. These houses must be affordable to low-income families, including those in low-paid work. The current model of Affordable Rent housing, at up to 80% of market value, fails to insulate people from the broken housing market and is not affordable in high cost parts of the country. JRF estimates the implementation of Affordable Rents will see 1.3 million more people in poverty in 2040[1] and place huge additional pressures on the Housing Benefit bill.

Boosting the supply of low-cost rented housing would offer an alternative to people currently trapped in the private rented sector — unable to afford home ownership and unable to access what low-cost rented housing exists:

It's all the fees and deposits and everything else you've got to put down on houses. It's these private landlords. I'd love to move into a council house but the list system is ridiculous at the moment... When we were at her mum's we bid every week for I think it was a year and we got nowhere.

Participant in JRF/University of York Housing and Life Experiences study

It may also reduce pressures on the wider housing market, particularly in the private rented sector.

Higher standards, more stability

Currently the most common form of low-cost rented housing is social housing. It provides lower housing costs, higher standards of decency and more stability for families. Four out of five current social renters say they are satisfied with their tenure status. Just one in ten are dissatisfied, compared to more than one in five private renters.

An under-appreciated success in recent years has been the improvement in housing quality within the social rented sector. Properties are now more likely to reach the ‘Decent Homes Standard’ in the social sector than owner-occupied or privately rented homes — whilst almost one in three low-income private renters living in poverty live in a non-decent home.

Social rented housing can offer secure tenancies, providing a stable platform for work, learning and life. This is particularly important for children, with evidence showing that frequent moves can result in behavioural problems and lower educational attainment among children.

Lower housing costs — for families and for government

The social rented sector lowers housing costs for families. 54% of low-income working-age households in the social rented sector spend more than one-third of their net income on housing costs, compared to 79% in the private rented sector.

Increasing the supply of low-cost rented housing will reduce the Housing Benefit bill. Analysis for JRF in 2015 showed that investing in 80,000 affordable homes per annum could reduce the Housing Benefit bill by £5.6 billion per annum by 2040, compared to a no-change scenario. Similar appraisals by Capital Economics and Savills use different assumptions but show similar potential for savings.

4. What the Social Housing green paper needs to do

The forthcoming Social Housing Green Paper must include measures to reduce the cost of housing for low-income families by increasing the supply of low-cost rented housing. It must also answer important questions about the location of supply, levels of rents, and management.

In his speech announcing the Social Housing Green Paper, the Secretary of State promised a ‘wide-ranging, top-to-bottom review of the issues facing the sector’. We have set out above why the Green Paper must set out a plan to bridge the 30,000 homes per year gap between current supply and objectively-assessed need. In addition, there are a number of questions the Green Paper should address regarding the location and management of these homes:

- Research for JRF suggests the principle housing factor affecting work incentives is the underlying level of rent. How will the Green Paper ensure affordability for those on low incomes and ease transitions into work?

- Our analysis above shows the acute pressures housing costs are exerting in London and the South East. How will the Green Paper target additional supply where it is most needed?

- There is good evidence of the negative impacts that mono-tenure neighbourhoods can have. How will the Green Paper ensure communities are mixed and well-connected to employment opportunities?

What could be done on supply?

In pursuit of lower-cost housing many organisations have devised partnership models aimed at harnessing the resources of the private sector, local and central government and housing associations. JRF has proposed a model to increase supply while ensuring rents are set at a level low-income working families can afford. The point is that we suffer not from a shortage of strong ideas but of resolve. The Green Paper must draw on this insight — along with that of current and prospective tenants — and include boosting the supply of low-cost rented homes as a priority.

A future JRF briefing will set out our own recommended solutions in more detail.

How to cite this briefing

If you are using this document in your own writing, our preferred citation is:

Robson, B. (2018) Using the Social Housing Green Paper to boost the supply of low-cost rented homes. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

This briefing is part of the housing topic.

Find out more about our work in this area.