Economic security as Labour's electoral foundation

Addressing voters’ economic insecurity will help Labour gain and retain support across the political spectrum, whereas prioritising a particular stance on immigration risks alienating voters on the other side of the issue.

- Executive summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. The JRF-Nuffield Economic Security Panel study

- 3. Economic insecurity: Stability and change

- 4. Economic insecurity is rooted in economic experience

- 5. Political context: Labour’s broad splintering, continued split on the right

- 6. 4 reasons economic security is foundational for Labour losses 2024–2025

- 7. Immigration is also important

- 8. Conclusions and political implications

- Appendix

- Notes

- References

- About the authors

- How to cite this report

- Executive summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. The JRF-Nuffield Economic Security Panel study

- 3. Economic insecurity: Stability and change

- 4. Economic insecurity is rooted in economic experience

- 5. Political context: Labour’s broad splintering, continued split on the right

- 6. 4 reasons economic security is foundational for Labour losses 2024–2025

- 7. Immigration is also important

- 8. Conclusions and political implications

- Appendix

- Notes

- References

- About the authors

- How to cite this report

Executive summary

Labour’s dramatic loss of support between 2024 and 2025 is especially pronounced among both left- and right-leaning voters who feel economically insecure. This insecurity also leads to reduced confidence in Labour’s ability to manage the national economy and heightens the importance of this lack of confidence for their decision to switch away from Labour.

While economic insecurity helps explain why Labour is losing voters to Reform UK, the Liberal Democrats and the Greens, increasing concerns about immigration only help explain Labour’s losses to Reform UK. Economic insecurity is therefore a more significant source of Labour’s current electoral challenges than immigration.

The Labour Government, and all political parties, must recognise the importance of the economy and ordinary voters’ feelings of financial or ‘economic’ insecurity. Economic insecurity is not simply about a person’s income or their social class; it is about the lived reality of financial anxiety. These feelings are central to well-being and are especially pronounced in mid-life (Nuffield Politics Research Centre, 2025), with economic insecurity experienced by around 34% of the adult British population in 2025.1 They are also vital for electoral support in their breadth of impact, and the way they are shaping Labour’s electoral losses since 2024.

The fortunes of Britain’s political parties rely, to a substantial degree, on whether people feel economically secure. Immigration, too, remains a lightning rod, threatening to redraw the political map for Labour and the Conservatives.

This report confronts the hard questions: how should Labour weigh the electoral risks of economic insecurity, especially given the dangers facing them on immigration? How should other parties respond in this volatile landscape? We do so by examining how changes in individuals’ economic insecurity and attitudes towards immigration influenced their tendency to stick with Labour or defect to other parties, or become undecided, between 2024 and 2025.

These changes are known as ‘within-person effects’, as they concern the impact of individuals changing their attitudes and vote intentions, rather than observed differences between people at a given point in time. The latter have often been observed in opinion polls, but we know very little about how individuals’ changing beliefs influence their votes.

Our findings are stark. Economic insecurity is draining Labour’s support across the spectrum, to both left and right, and to ‘undecided’. The effects of economic insecurity are particularly important due to their breadth. Our within-person analysis indicates that moving from economic security to insecurity is associated with, at minimum, a 5.45 percentage point increase in the probability of defecting to Reform; a 3.42 percentage point increase in the probability of defection to the Lib Dems; and a 4.15 point increase in the probability of switching to ‘undecided’, currently the largest group of Labour’s vote losses. In contrast, the within-person effects of immigration attitudes are limited to the smaller proportion of Reform switching.

Moving from supporting further immigration to opposing further immigration is associated with, at minimum, a 4.08 percentage point increase in the probability of defecting to Reform, but it has no impact on the likelihood of defecting to other parties or to ‘undecided’. Overall, due to its impact on defections to a bigger range of parties, becoming economically insecure increases the chance of defection 3 times more than becoming anti-immigration.

The ways in which economic insecurity is affecting Labour’s support are both direct, pushing voters away, and indirect, by shaping whether people trust Labour on the national economy, magnifying doubts about Labour’s economic management for voters on the left and right, and compounding concerns about Labour’s handling of immigration.

To be clear, economic insecurity does not increase voters’ concerns about Labour’s handling of immigration, or people’s underlying attitudes about immigration. But it does make concerns about immigration more relevant to decisions about which party to defect to: of those who are concerned about too much immigration, the economically insecure are more likely to switch to Reform UK.

Generally, however, concerns about immigration are more important for voters who have defected to Reform UK from the Conservatives after their 2024 defeat. These immigration-related Conservative losses matter. Should Reform UK become the electorally dominant party of the right, it will be able to win key constituencies and dramatically improve its ratio of seats to votes, in the process stripping Labour of much of its advantage in this respect in the 2024 election.

Our findings are based on analysis of 3 large surveys of panel data, the ‘JRF-Nuffield Economic Insecurity Panel Study’, which were collected in March 2024, October 2024 and April 2025. Each survey wave contains around 8,000 respondents, with around 4,500 individuals participating in all 3 waves. We also use data from the British Election Study. Unlike simple opinion polls, our data tracks the same people over time, so we can be more confident about what has changed since 2024.

This lets us estimate how important economic insecurity and immigration attitudes are for different types of voters, using actual changes in people’s experiences and their voting intention rather than just what people say is important.

Reasons feelings of economic security are foundational for Labour

We identified 4 ways economic insecurity is undermining Labour’s 2024 support:

- People who feel financially insecure are leaving Labour in greater numbers than those who do not feel insecure. These anxieties are rooted in economic experience, in savings, home-ownership, job tenure, outgoings, debts and risks, perceived ability to rely on the welfare state, and household income (Nuffield Politics Research Centre, 2025).

- Feelings of financial insecurity make people rate Labour’s handling of the economy more negatively. This matters because ratings of Labour’s economic management are also important for how people vote. Improving financial security would help Labour’s reputation for managing the economy and boost its electoral prospects.

- Financial insecurity makes people care even more about how Labour manages the economy. Insecure Labour voters are more likely than others to ‘punish’ the Government by switching parties if they think Labour is doing a bad job in its handling of the national economy, and they do so irrespective of which party they switch to. This means that improving financial security could reduce Labour’s net vote losses on its handling of the national economy too.

- Among some voters, namely, the 2024 Labour supporters now planning to vote Reform UK, or Liberal Democrat, economic insecurity provides a grievance that makes people more likely to move to parties that better reflect their views on immigration. Improving financial security would therefore also reduce Labour’s losses associated with immigration, on both the left and right.

To provide insight into their relative importance, we compare the relevance of feelings of economic insecurity to attitudes about immigration. We conclude:

- Economic insecurity is a broader explanation for Labour’s losses than are immigration-related grievances. While the latter are important for providing the party affiliation for some people to defect to, increasing economic insecurity also drives this defection, for both more pro-immigration voters moving to the left and immigration sceptics moving to Reform UK.

- Experiences of economic insecurity are quite different from a person’s underlying attitude towards immigration.

- Increases in economic insecurity influence vote intention in a broad way, with people defecting from Labour both to the right (Reform UK) and the left (the Liberal Democrats and Greens). In contrast, changes in views on immigration will ‘net out’ for Labour. For example, an increasingly hard line on immigration could reduce the flow of votes to Reform UK, but may well increase losses on the left.

- Immigration attitudes are important as drivers of continued Conservative losses to Reform UK, which has been gaining voters on the right, and from non-voters since 2024. There are no effects of economic insecurity on Conservative losses since the party left office.

Implications

It is very difficult to weigh electoral calculations in a volatile and fragmented context. It is also difficult to simply ‘make’ people feel economically secure. However, our analysis suggests that a policy approach and political strategy of prioritising an ‘economic feel-good factor’ for both the national economy and for individuals and households would have multiple electoral benefits to Labour, and would lead to vote gains across the political spectrum. It would, of course, also have multiple benefits to the population.

If Labour sought to prioritise vote losses on the immigration issue, however, our analysis suggests that this decision would likely lead to vote losses as well as gains. These losses would be significantly mitigated if people also felt more economically secure.

1. Introduction

UK politics has become increasingly complex, both for voters to make sense of, and for political parties trying to govern and compete electorally. This complexity arises because support for mainstream political parties is fragmenting (Miori and Green, 2025), and because the traditional dominant competition on ‘left–right’ issues has been accompanied by issues such as immigration, and related attitudes that cut across the traditional left–right axis (Sobolewska and Ford, 2020).

Many aspects of the last UK general election were historically unprecedented (Miori and Green, 2025), and political and electoral volatility is continuing apace. There has been an unusually large drop in support for the Labour Government over its first year, and an exceptional rise in support for Reform UK in opinion polls. This was all expressed in the recent local elections (Green and Miori, 2025), where other minor parties also made notable gains.

Two political issues stand out in opinion polls as being the most important to people in 2025: the economy and, increasingly, immigration (YouGov, 2025a). However, simply talking about or trying to address these 2 issues may involve trade-offs in terms of how the public responds. They each involve difficult political calculations.

For example, if Labour shifts to a more hostile position on immigration, it may lose its support on the left that delivered Labour its majority in 2024 (Griffiths, Perrett et al., 2025). If other political parties focus primarily on immigration, they may lose out on support among people who are more concerned about the economy. These issues need to be understood in tandem, not separately.

The relationship between economic insecurity and immigration-related grievances is complex. While cross-national research demonstrates that working-class voters are more likely to oppose immigration than middle-class professionals (Lindh and McCall, 2020), the extent to which labour market competition or other negative economic experiences — as opposed to social status threats or cultural preferences for greater homogeneity and order — drive anti-immigration sentiment is heavily disputed (Hainmueller and Hopkins, 2014; Pardos-Prado and Xena, 2018).

We do not aim here to adjudicate between competing claims on the causes of anti-immigration sentiment. Rather, British politics needs to be seen as a combination of both economic and cultural concerns. Since the 2016 European Union Referendum, voters have become increasingly ‘sorted’ into 2 competing ‘party blocs’ as they have chosen parties based on their attitudes to sociocultural issues, as well as other factors (Griffiths, Perrett et al., 2025). There is a more ‘liberal’ side (encompassing Labour, the Liberal Democrats, nationalist parties and the Greens), and a more ‘conservative’ one (encompassing the Conservatives and Reform UK).

However, while immigration attitudes can help explain the existence of these 2 blocs, we argue that economic insecurity is a key factor in explaining their fragmentation and, in particular, Labour’s vote losses to other socially liberal parties like the Greens and the Liberal Democrats since 2024.

Economic insecurity can cause this fragmentation not only directly (that is, people leaving Labour because they feel insecure) but also indirectly, by interacting with the immigration issue itself. This indirect effect is accentuating both the 2-bloc nature of contemporary British politics, as well as the fragmentation within those blocs. Additionally, while switching between parties on either side of the bloc divide is currently rare, our analysis shows that economic insecurity plays an important role when it does occur.

This means, for instance, that Labour is suffering particularly high rates of defection among economically insecure voters who are both particularly pro-immigration (mainly to the Liberal Democrats and ‘undecided’) as well as those who are particularly opposed (to Reform UK). In this respect, continued insecurity under a Labour administration is serving as something of a ‘final straw’, convincing voters unsatisfied with Labour to defect to parties which better align with their values on issues like immigration.

To add to this understanding of the interplay between economics and immigration attitudes, we need to correctly understand how ‘the economy’ matters to people, and how it might be expressed and weighted. Clearly, ‘the economy’ is what happens at a national level as well as what happens to people in their daily lives. How the national economy is doing is a signal of governing competence, as well as something that can materially affect people, and so a growing economy is extremely important for governing parties. It tends to give them greater electoral support and makes their spending decisions easier.

Deteriorations or improvements in the national economy are broad signals in elections that cut across ideology, and so they tend to be important across the board for different types of voters, rather than involving trade-offs between ideological groups. Immigration, on the other hand, typically has asymmetric effects (Kustov, 2022), with those most concerned about immigration being more responsive on the political right.

The broader concept of ‘economic security’ helps us understand people’s economic experiences in several important ways:

Economic security captures people’s broad financial circumstances, including not only income but also savings, debts, job tenure, homeownership, outgoings (such as having dependants) and whether people think they could rely on benefits if needed. This evidence is presented within this report.

Economic security therefore gives us a much broader insight into the full range of experiences that make someone secure to make choices that may benefit them and their family, and helps us understand, in particular, the range of experiences that happen over the life cycle (Nuffield Politics Research Centre, 2025), meaning, for example, that retirees typically have smaller incomes but higher levels of economic security in today’s UK economy.

Economic insecurity is a broad experience across the population and exists even for proportions of people or households on middle or high incomes (Nuffield Politics Research Centre, 2025), but for whom outgoings, mortgage debt and a lack of financial ‘buffers’ such as savings mean that people feel a greater sense of anxiety. For example, in our latest survey, examined throughout this report, we find that 34% of the British population report feeling economically insecure.

This means that while the experience of poverty is acute and debilitating for opportunities, health and wider well-being (JRF, 2025), we need to understand that economic insecurity can also have debilitating effects, and improving economic security would have widespread benefits to the population and the national economy.

- Feelings of economic insecurity represent worries and emotions about financial circumstances, and analysing these worries gives us powerful insight into the potential drivers of other attitudes and political choices that would not be possible, for example, just by knowing someone’s objective economic circumstances. Objective circumstances tell only part of the story. Often people wish for different economic circumstances or hold uncertainties about the future, so knowing how people feel about their economic position is extremely informative.

Our previous work has shown the electoral importance in Great Britain of feelings of economic security. In a report published in 2022, we demonstrated (Green and de Geus, 2022) the economic associations with feelings of economic security, and how the major parties — Labour and the Conservatives — were broadly still the parties of the insecure (Labour) and the secure (Conservatives). Our more recent work (Nuffield Politics Research Centre, 2025), together with the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF), has shown how economic insecurity peaks for adults in ‘mid-life’, those between the ages of 35 and 59.

Understanding the distribution of economic insecurity by age has important policy implications, but age has become a critical fault line in political behaviour too, and so understanding the distribution of economic insecurity over the life-course is extremely important for politics. Adults in mid-life are both the most economically insecure and, as of October 2024, were the most ‘volatile’ in their vote choices, meaning they are critical ‘swing-voters’ in British politics.

This current report delves more deeply into the political implications of economic insecurity and immigration attitudes to offer a broader understanding of how feelings of economic insecurity are shaping voter volatility since the UK 2024 General Election.

2. The JRF-Nuffield Economic Security Panel study

The Nuffield Politics Research Centre (NPRC; based at Nuffield College, University of Oxford) and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) have designed several large, nationally representative surveys, each of around 8,000 people, as part of an internet survey ‘panel’ in which as many of the same people as possible are interviewed in subsequent survey ‘waves’. This design allows us to examine the implications of entering and exiting different types of economic pain or gain and provide insights into the drivers and consequences of economic insecurity through analysis of the temporal ordering of experience and outcome.

Our existing surveys took place in March 2024 (Wave 1), October 2024 (Wave 2), and April 2025 (Wave 3).2 While most of the 8,120 respondents who were contacted in March 2024 remained in the sample at subsequent waves — ‘retention’ was around 75% for Wave 1 to Wave 2, 71% for Wave 2 to Wave 3, and 57% remained in the panel for all 3 waves — each sample was ‘topped up’ with new respondents to ensure more than 8,000 total responses in each instance.

The implementation of these surveys was conducted by the leading UK online survey company, YouGov, which also provided weights sufficient to ensure that our sample pool is representative of the broader British population in terms of age, education, party support, and other important predictors of economic experience and political attitudes (YouGov, 2025).

Throughout this report, we occasionally supplement this analysis using the authoritative British Election Study Internet Panel (2025), which is also fielded online with YouGov, ensuring a demographically and politically representative sample, though with a larger sample size.

3. Economic insecurity: Stability and change

Our 3 waves of data, which cover a period of 13 months from March 2024 to April 2025, allow us to analyse stability and change in economic insecurity. We measure economic insecurity by asking respondents, ‘How worried are you about you and your family’s economic security?’, where responses were measured on a scale between 0 (‘not at all worried’) and 10 (‘very worried’).

Using this measure in the 3 waves, we first explore changes in this measure at the aggregate or national level. To do so, we calculate the average (mean) score on the economic insecurity scale across all survey members at each wave, excluding those who answer ‘don’t know’. This reveals that, at the aggregate level, insecurity has remained stable over our survey. At Wave 1 (March 2024), the mean score for economic insecurity was 5.36 (on the 0–10 scale); at Wave 2 (October 2024), the mean score was 5.41; and at Wave 3 (April 2025), the mean score was 5.38.

While our data suggests that economic insecurity at the national level has remained stable, individuals may have still experienced considerable change in their own economic insecurity. As our survey is a ‘panel’, we can measure change in economic insecurity by the same individuals across all 3 waves. This allows us to capture the evolution of our survey members’ economic experiences and determine, for example, the number of people who become insecure, or the number who move into a more secure financial situation.

To visualise individual-level change in economic insecurity over time, we first convert our 0–10 economic insecurity scale into 3 groups or categories: respondents who provide a score of 7–10 are classified as ‘insecure’; those who provide a score from 0–3 are classified as ‘secure’; and those who provide a score from 4–6 are grouped into a middle ‘neither’ category.

We then calculate the number of people who switch between categories and present these in tables called transition matrices. In Tables 1 and 2, we present 2 of these transition matrices: one to represent changes in economic insecurity from Wave 1 to Wave 2, and one to represent changes from Wave 2 to Wave 3.

Each transition matrix is simply a 3-by-3 table, with each cell reporting the number of people who have changed (or transitioned) from one category of insecurity to another from one wave to the next, or the number who have remained stable in the same category over the 2 waves. Each cell provides these numbers as a proportion of the total number of people who provide a response to the economic insecurity scale in both waves (in percentages), along with the underlying number of people who make each transition.3

| Wave 2: Secure | Wave 2: Neither | Wave 2: Insecure | Total (N) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1: Secure | 19.25% (1089) | 7.67% (434) | 2.51% (142) | 1,665 |

| Wave 1: Neither | 6.26% (354) | 20.49% (1159) | 8.26% (467) | 1,980 |

| Wave 1: Insecure | 1.77% (100) | 9.1% (515) | 24.68% (1396) | 2,011 |

| Total (N) | 1,543 | 2,108 | 2,005 | 5,656 |

| Wave 3: Secure | Wave 3: Neither | Wave 3: Insecure | Total (N) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 2: Secure | 18.99% (1065) | 6.94% (389) | 1.46% (82) | 1,536 |

| Wave 2: Neither | 6.15% (345) | 22.99% (1289) | 7.81% (438) | 2,072 |

| Wave 2: Insecure | 2.3% (129) | 9.01% (505) | 24.34% (1365) | 1,999 |

| Total (N) | 1,539 | 2,183 | 1,885 | 5,607 |

As Tables 1 and 2 display similar patterns, we discuss them together.

The most frequent pattern among our respondents is stability, with nearly two-thirds remaining stable in the same category of economic (in)security from one wave to the next — 64.43% from Wave 1 to Wave 2, and 66.33% from Wave 2 to Wave 3. These totals are calculated by summing the percentages in the diagonal cells running from top left to bottom right.

Transitions into adjacent categories happen more frequently than a ‘jump’ across 2 categories (such as from being economically insecure at one wave to economically secure at the next). We also see that the proportion of respondents who transition into economic insecurity is similar to that which moves into economic insecurity: 10.76% transition into economic insecurity and 8.03% transition into economic security from Waves 1 to 2; from Wave 2 to Wave 3, the corresponding percentages are 9.27% and 8.45%.

These transition matrices show that, in our survey, there are large numbers of people who experience stable feelings of economic (in)security from one wave to the next, along with 35% who experience change, although this is primarily a move between either secure and neither, or insecure and neither.

Throughout this report, we make use of these multiple waves of data by using 2 kinds of analysis to understand the role of economic insecurity in shaping voting decisions. First, there are the changes in an individual’s responses to questions on their economic insecurity, or any other matter, across the waves of the panel survey. This is referred to as a ‘within-person effect’.

These within-person changes isolate the impact of a change in a person’s responses over time, because they control for all stable characteristics of that person (like their background, values, personality, or other typically stable political preferences like partisanship). They therefore help to establish whether a change in, say, economic insecurity actually causes a change in voting behaviour. By tracking the same individuals over time, we can therefore see if becoming more insecure leads to a change in voting behaviour. This is the big advantage of panel studies over one-shot surveys.

The second type of analysis compares the political choices of people who are economically secure with those who are economically insecure, a ‘between-person’ analysis. Between-person effects help us understand differences between groups. For example, we can say that, on average, economically insecure people are more likely to defect from Labour than economically secure people. In combination these 2 approaches allow us to understand the consequences of stable differences in economic insecurity and of changes in people’s experiences.

4. Economic insecurity is rooted in economic experience

Using the first 2 waves of our panel study, we previously demonstrated (Nuffield Politics Research Centre, 2025) that feelings of financial insecurity were predicted by a range of real world ‘objective’ economic experiences. These included respondents’ levels of household income, savings, and access to secure employment, but also their outgoings in terms of debts, childcare duties, and housing.

Using the most recent wave of our panel, from April 2025, we provide a partial replication of these earlier findings. Using the 3-category measure of economic insecurity described above, we predict the probability of being insecure using a range of variables based on our findings in the previous report.

Specifically, we predict insecurity using respondents’ gross household income, their total household cash savings, their employment status and the perceived security of their employment contract (amongst full-time employees), their homeownership status, their childcare responsibilities, their holding of ‘bad’ debts, their disability status, and their belief in the extent to which they could rely on the UK benefit system to support them if they really needed.

Gross household income and savings are both equivalised for the number and adult/child status of members of the household, and they are expressed in standard deviation increments. ‘Employment contract’ distinguishes those who are in full-time employment, part-time employment, retired or not in work for any other reason (for example, unemployed, too sick to work, caring for others and so on).

We then further subdivide full-time employees into 2 groups depending on their level of agreement with the statement ‘I am very worried about keeping my job’. Those who agreed or strongly agreed with the statement are classed as being in ‘insecure full-time employment’, with those disagreeing or stating that they ‘neither agreed nor disagreed’ classified as in ‘secure’ employment.

For homeownership, we distinguish non-homeowners from those who own outright and those who are currently paying their mortgage. Childcare responsibilities simply distinguish those who currently have financial responsibilities for a child aged under 18 and those who do not.

‘Bad debts’ are those that are not backed by collateral, subject to earnings-related repayment thresholds or given informally from a friend or relative. They hence include credit card borrowing, short-term or ‘payday’ loans, overdraft borrowing or any other type of unsecured loan such as hire purchase or ‘buy now, pay later’ schemes (but not tuition fees or mortgage debt). We distinguish between those who have such debts and those who do not.

Finally, a perceived ability to fall back on the social safety net in hard times was gauged by asking respondents whether they agreed or disagreed that ‘I can rely on the benefit system to provide for me in the future, if I need it’. Responses ranged on a 5-point scale from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’, but here we also express the coefficient in terms of standard deviation increases in agreement.

We also include in our models 4 ‘control’ variables. These are respondents’ age, gender, education (no GCSEs, only GCSEs, only A-Levels or vocational, undergraduate degree or higher), and party identification (Labour, Conservative, Other Party, None, Don't know). However, we do not visualise the association between these ‘control’ variables and economic insecurity in the subsequent figure, as we are interested here in the relationship between economic circumstances and economic insecurity.

Logically, we should expect insecurity to fall with the accumulation of various ‘assets’ (such as having a higher income, greater savings, a secure job and owning property), and rise with the accumulation of various ‘liabilities’ or burdens that necessitate greater financial outgoings (such as having childcare responsibilities, indebtedness or a disability). Those who feel that they could rely on the benefit system to support them if they needed it should also be less insecure, given their relative faith in the existing social safety net.

But how do these expectations fare in practice? Figure 1 presents the results of a statistical analysis that examines the strength of relationships between our samples’ sociodemographic characteristics and financial experiences and their likelihood (displayed in percentage point terms) of being economically insecure.

How does one interpret Figure 1? The main thing to note is that the plot contains blue circles, known as ‘coefficients’, representing our best estimate of how strongly associated a given factor (or ‘variable’) is with a lower (if before the vertical line) or higher (if after) likelihood of being economically insecure in April 2025. The whiskers associated with each coefficient are ‘confidence intervals’ and can be interpreted as the range of values that we think are reasonably possible for that coefficient, given the data.

Importantly, this statistical analysis — formally known as a linear regression — is a ‘multivariate’ analysis. This means that each coefficient represents the relationship between a given variable and the probability of someone being economically insecure, after we have taken into account (‘controlled for’) that person’s values on any other variable in the model. For instance, the coefficient for ‘household savings’ tells us how much less likely someone is to be insecure if they have greater household savings than someone who has fewer, even if we were comparing people of the same gender, or identical age, educational attainment, household income (and so on for all other listed variables). That is, we are ‘isolating’ the effect of each variable from all the others.

The one final thing to remember is that, while some coefficients can be interpreted straightforwardly (for example, ‘income’ tells you how much each greater income increment reduces the probability of insecurity), some, namely housing and employment status, tell you how much a certain condition matters in relation to some other 'reference category’. For instance, for the variable ‘housing tenure’, the coefficients for ‘own property outright’ and ‘own with a mortgage’ tell you how much less likely respondents who own property outright or with a mortgage, respectively, are to be insecure than a ‘non-owner’ (again, after controlling for all other variables in the model).

Similarly, the coefficients for the other categories of the variable ‘employment status’ tell you how much less likely respondents in those categories (for example, the retired or those with secure full-time employment) are to be insecure than the reference group of those with insecure full-time employment (again, net of all other variables in the model).

Substantively, having a higher income, greater savings, a secure full-time job or being retired, and owning property (particularly outright) are all associated with lower probabilities of being subjectively economically insecure. As is a person’s belief that they can rely on the UK benefits system if needed. In contrast, having childcare responsibilities and unsecured debts, as well as having a disability, not owning property and being in insecure work or lacking employment at all, are all associated with a greater likelihood of insecurity.

So economic insecurity can stem from multiple different sources, and it is a broader concept than simply income and employment (and so on) alone. But how might it help us explain contemporary British politics?

5. Political context: Labour’s broad splintering, continued split on the right

There are 2 key features of voter volatility in the past year, which build on the already highly unstable electoral dynamics preceding and evidenced in the 2024 General Election (Griffiths, Perrett et al., 2025). The first is the broad splintering of Labour’s support between 2024 and 2025. Crucially, Labour’s support in 2024 (34%) was exceptionally low for a majority-winning party by historic standards. This meant that a further loss of support would be extremely serious for Labour, and this has indeed come to pass very quickly relative to other recent incoming governments (Griffiths, Fieldhouse et al., 2025).

The second feature is the further, additional and cumulative split on the right, which already played a crucial role in the Conservative Government’s defeat in 2024, and which has continued since. This cumulative split is seriously damaging for the Conservatives in votes and seats, but it is also very harmful for Labour in seats, as we discuss later.

Both features can start to be seen in the vote flow diagram in Figure 2, which shows the origins and destinations of voters and non-voters between the December 2019 and July 2024 General Elections and May 2025, using Waves 19, 29 and 30 of the British Election Study Internet Panel. The percentages depicted are lower than parties’ official 2019 and 2024 vote shares because we include non-voters in the denominator. This is important, especially because turnout was so low in 2024 in particular (59.7%) (UK Parliament, 2024).

The available votes for the parties following such a low turnout election inevitably includes higher numbers of 2024-era abstainers, and we do see portions of this group now expressing a vote intention. Similarly, when we report current (as of May 2025) vote shares, we also include the figures for those intending to abstain (though this will likely be an underestimate of the ultimate figure) as well as those who are currently uncertain about their vote choice. Together, this explains why the party vote shares displayed will be different (lower) than in most polls. Finally, our data is from Britain only and hence does not include the vote share going to parties in Northern Ireland.

From the graph, one can make out the patterns of volatility and fragmentation that have characterised the British party system in recent years. That is, there are substantial vote flows into and out of the parties during the 2019–2025 era (indicative of people switching their party preference regularly), and both the ‘left-’ and ‘right-wing’ party ‘blocs’ have become more evenly balanced between multiple parties as support for the Conservatives and (eventually) Labour has declined.

The Conservatives had a historic challenge in 2024 with a dramatic fall in their vote share, from 43.6% in 2019 to 23.7% in 2024, their worst ever performance. This equates to a change from 33% in 2019 to 19% in 2024 when expressed as a proportion of the whole electorate. Extending our analysis to May 2025, we see that the Conservatives have lost around two-thirds of the vote coalition that they gathered to win the 2019 General Election, with most of these voters going to Reform UK, either in 2024 or the year following.

This inflow, along with gains among previous non-voters, has helped propel Reform into first place, with support rising from around 2% of the electorate to 23% between 2019 and 2025. This is made easier for Reform because the 2 largest parties’ support has been ebbing away, making ‘first place’ a lower bar.

While the ‘right-wing’ bloc has split in 2 between 2019 and 2025, the ‘left-wing’ bloc has become even more fragmented. The 2024 Labour vote resulted from modest increases in support between 2019 and 2024 (from 25% to 27% as a proportion of the electorate), originating across the ideological spectrum.

British Election Study data showed that, among the relatively small number of voters switching to Labour between 2019 and 2024, 35.8% were from the Conservatives, 27.4% were from the Liberal Democrats, 5.9% were from the Greens, and 11.9% were from ‘others’ (with the remainder being previous non-voters). This was a very small total increase in vote share, but one which delivered Labour a very large majority because of its fortuitous geographic distribution (Miori and Green, 2025), which arose from the split of the Conservative vote on the right, tactical voting among progressive voters, and 2 unpopular incumbent governments: the devolved Scottish Nationalist Party Government in Scotland, and the Conservative Government in Westminster.

Though Labour made modest gains between 2019 and 2024, they have shed substantial numbers of supporters — almost two-fifths when expressed as a proportion of the electorate that previously supported them — during their first year in office.

Given the ‘bloc’-based nature of politics post-Brexit (Griffiths, Fieldhouse et al., 2025), these losses have mostly been to other socially liberal, centre-left parties (the Greens and the Liberal Democrats), but they have also lost some voters to Reform UK and, in particular, to ‘undecided’. Whether these undecided voters — equivalent to almost 1-in-5 potential voters as of May 2025 — ultimately return to their 2024-era parties, opt for a new political home, or abstain entirely will have a big influence on the outcome at the next election.

This cumulative ‘vote flow’ diagram is good for getting a sense of the degree of overall fragmentation and volatility in contemporary British politics, but to really get a sense of where both major parties are losing voters since 2024, we visualise the direction of losses to Labour and the Conservatives ‘losses’ expressed as a percentage of their previous vote share. These are shown in Figures 3 (for Labour) and 4 (for the Conservatives).

Starting with Labour, in Figure 3, we can see that the party has lost over half (51%) of its 2024-era supporters as of May 2025. With roughly even proportions going to the Greens (8.2%), Liberal Democrats (9.4%) and Reform (7.9%). Very few Labour voters have defected to the Conservatives (2.3%), as we might expect given that party’s continuingly weak showing in opinion polls.

Optimists within Labour might point to the fact that the single largest proportion of defectors have become ‘undecided’ (18.9%) rather than defecting to a specific rival party. As we will later show, combating economic insecurity may be key to winning back these (and other) defectors between now and the next election.

Figure 4 shows that, while Labour’s vote has fragmented in many directions – left, right and centre – the story for the Conservatives is very much one of ‘revolt on the right’. Like Labour, the Conservatives have lost over half (51.1%) of their 2024-era supporters, but these voters have mostly gone in one direction: to Reform UK.

Reform UK have picked up 3-in-10 2024-era Conservatives (29.8%), whereas only 1-in-25 have gone to either of the Greens, Labour or the Liberal Democrats. As with Labour defectors, a substantial number have also switched to being ‘undecided’ (15.8%), and it may be these supporters that could prove most liable to be won back in the coming years.

The context is important here. It is exceptional and unprecedented for a party that has lost an election after being in government to continue to lose even more support than it gains. These 2024–2025 patterns are continuations of patterns that took place between 2019 and 2024, when the Conservatives started to shed supporters to Reform UK.

As we demonstrated in our previous report (Nuffield Politics Research Centre, 2024), the Conservatives were heavily punished when they were in office, with the party’s losses (to both Reform UK and Labour) being highest among economically insecure ex-supporters.

Clearly, however, a large part of the overall story of the Conservatives between 2019 and 2025 is the rivalry with Reform UK and the split of the right-wing vote (which, as we shall show, also owes a lot to continued grievances over rates of immigration). If we zoomed out to look at the total story between 2019 and May 2025, our numbers would show that the Conservatives have lost fully 72% of those who supported Boris Johnson’s government at the 2019 election, with almost half of these previous supporters (44.8%, or 62% of all defectors) now opting for Reform UK.

As our earlier overall ‘vote flow’ diagram (Figure 2) showed, whatever few gains the Conservatives have made from other parties or non-voters is clearly not enough to compensate for this haemorrhaging of support on the right.

Another way to look at this continued split is to consider the composition of Reform’s vote over time (not displayed). In May 2025, 41.9% of Reform’s post-July 2024 gains — that is, excluding those already voting for the party at the last election — came from 2024 Conservative voters, 16% from Labour and 32.6% from non-voters.

If we zoomed out to take a longer perspective that would encompass the entirety of Reform’s growth since 2024 (as visualised in Figure 2), we would see that of Reform’s May 2025 supporters, well over half (58.9%) voted for Boris Johnson’s Conservatives in the December 2019 General Election. Almost another quarter were those who did not vote in that election (22.2%), and only around 1-in-10 (9.7%) were Labour supporters in 2019.One must go back multiple elections, to the Blair era, to see substantial numbers of current Reform’s supporters, via UKIP and the Brexit Party, originating from Labour defectors, because of the way the Labour and Conservative parties’ voters have changed over time (Griffiths, Green and Fieldhouse, 2024).

These patterns — of broad splintering of Labour’s support, and the continued ‘split on the right’ — are outcomes that have their foundation in the ‘Brexit realignment’ that has organised voters into 2 electoral blocs (Griffiths, Perrett et al., 2025): a Conservative-Reform supporting bloc that supports or supported ‘Leave’ in the Brexit referendum and is broadly right-of-centre and more socially conservative; and a Labour-Liberal Democrat-Green and nationalist supporting bloc that supports or supported ‘Remain’ in the Brexit referendum and which is broadly left-of-centre and more socially liberal.

Labour’s 2024 vote was predominantly comprised of the latter bloc, which explains the dominant direction of vote losses to the left, or to undecided, as opposed to Reform UK. The Conservatives’ 2019 and 2024 votes were predominantly comprised of the former bloc, which explains the dominant direction of vote losses to the right.

Indeed, the strong alignment of ‘Leave’ and socially conservative voters with the Conservatives following their stronger rightward shift post-Brexit, meant that their vote, if they lost support as they did during their period in office between 2019 and 2024, would most naturally split right with competition from another right party, which Nigel Farage supplied in Reform UK. This right-wing split and the rise of Reform are consequences of the Brexit realignment under May and Johnson, and the subsequent implosion of support for that government.

Sceptics might highlight that a large proportion of both Labour and the Conservatives’ July 2024-era supporters — 19% and 16%, respectively — are ‘defecting’ to ‘undecided’ rather than to any other named party. Although we can see evidence for ‘bloc’-based patterns of defection when looking at those naming a preferred other party, it would clearly complicate this picture if the large number of voters that Labour is losing to ‘uncertainty’ actually tended to prefer right-wing parties. Indeed, this might give some indication that these voters were on the way to Reform. Likewise, the argument about party blocs would also be weakened if many of the Conservatives’ losses to ‘uncertainty’ actually preferred more centrist or left-wing options to Reform.

One way to get a sense of where these currently undecided voters are likely to end up is to use their responses to various ‘propensity-to-vote' (PTV) questions embedded in the British Election Study. Respondents were asked, ‘How likely is it that you would ever vote for each of the following parties?’ They then rated each of the larger UK parties from 0 (‘Very unlikely’) to 10 (‘Very likely’). Don’t knows were excluded.

Figures 5 and 6 below visualise the average PTV score assigned to the Greens, Liberal Democrats, Labour, the Conservatives and Reform (aligned roughly left-right as far as sociocultural issues go), among currently undecided voters who supported Labour (Figure 5) or the Conservatives (Figure 6) at the last general election.

As can be seen, observing the self-declared, most-likely destination of the currently undecided — were they to support any party — shows that the patterns of bloc-based defections that we have identified remain corroborated. Ex-Labour supporters assign a far higher PTV score to parties on their left, in sociocultural terms, than parties on the right. Indeed, currently undecided, ex-Labour voters give a particularly low PTV score to Reform, suggesting it is highly unlikely that Nigel Farage can make many further gains from Labour's 2024-era coalition.The roughly 1-in-5 voters that Labour has lost to ‘uncertainty’ since July 2024 are not Reform UK voters in disguise.4

Conversely, of course, among undecided ex-Conservative voters, Reform is clearly more popular than Labour, the Liberal Democrats and (in particular) the Greens. The Conservatives have more to worry about to their right than to their left here, which was the lesson from the vote flow graphics above.

Finally, of course, it is notable that among both sets of ‘defectors’, the party of origin gains the highest ‘PTV’ score (that is, currently undecided ex-Labour or, in particular, ex-Conservative voters are more likely to say they will vote for that party than any other). This is a further reminder that not all of these defectors are lost forever, and both major parties could win back this support with the right offer.

To what extent might a harder position on immigration help win these voters back? This is important for our report, because we are focused on understanding the relative weighting of people’s economic insecurity and their immigration preferences on the current patterns of switching. If Labour’s smaller losses to Reform are characterised by anti-immigration attitudes, but their much greater losses to undecided, the Greens, and the Liberal Democrats are comprised of voters with more liberal attitudes, Labour’s difficulties with dealing with the immigration issue become more apparent.

In Figure 7, we present the distribution of attitudes to immigration among 2024 General Election Labour supporters according to their present (May 2025) vote intention. Immigration attitudes are measured using a question in the NPRC/JRF Economic Insecurity Study that asked respondents, ‘How much would you support or oppose a government making it easier for immigrants to come to Britain to work?’

We distinguish between those who would support (or strongly support) the proposal, those who would oppose (or strongly oppose) it, those who neither support nor oppose it, and those who say ‘don’t know’. We visualise the attitudes of ‘Labour loyalists’ who continue to support the party as of May 2025 and ‘Labour defectors’ who moved to supporting other parties, being undecided or intending to abstain.

Observing the attitudes of those moving from Labour to specific rival parties is difficult due to the relatively small subsamples available in our JRF/NPRC panel (from which the immigration measure is derived). This forces us to group parties together in broad groups. Accordingly, we then also present the distribution of attitudes among those defecting to ‘left-liberal’ parties (that is, the Greens, Liberal Democrats, SNP or Plaid Cymru), to ‘right-conservative’ parties (that is, the Conservatives or Reform UK) and to ‘Undecided’. As shown earlier, in Figure 3, these groups are comprised of roughly 19%, 10% and 19% of July 2024 GE Labour supporters who were re-interviewed in May 2025.

The results speak to the difficulty that Labour may have in seeking to mobilise current and past supporters on the basis of the immigration issue. While, overall, those voters whom Labour have lost since July 2024 tend to be somewhat more anti- than pro-immigration (by 39% to 26%), remaining Labour voters tend to be slightly pro-immigration on average (that is, they split 33% to 25% in the other direction).

Furthermore, there are large numbers among both groups (36% and 42%, respectively) who are either undecided or neutral on the issue. While it is not the case that current or previous Labour supporters are dramatically in favour of increased rates of immigration, nor are they easily pigeonholed as staunch opponents.

Things are more interesting still if we look at the attitudes among those defecting in different directions (left, right or undecided). While, as we might expect, those defecting to Reform UK or the Conservatives tend to overwhelmingly disagree with proposals to further liberalisations of the immigration system, opposing the statement by 73% to 9%, the more numerous Labour defectors to ‘left-liberal’ parties or to ‘undecided’ tend to be more liberal or at least moderate on the issue.

Defectors to ‘left-liberal’ parties (that is, Liberal Democrats, SNP, Plaid Cymru and the Greens) show more support than opposition (42% to 22%), and the undecided are also less uniformly hostile (22% support to 32% oppose). Furthermore, over one-third of ‘liberal-left’ defectors, and close to half of all currently ‘undecided’ defectors, are simply neutral or undecided on the immigration question. This clarifies the dilemma for Labour.

While it is conceivable that signalling strong opposition to immigration might help the party claw back some losses to the Conservatives or Reform UK, it is unlikely to be a panacea or even a particularly effective stopgap in regaining the heavier losses to left-liberal parties or the undecided, or even maintaining the supporters sticking with it for the time being.

This helps to understand where voters are going to and where they have come from, but it does not explain why. This is the question we turn to next.

6. 4 reasons economic security is foundational for Labour losses 2024–2025

We show in this section that Labour’s vote is splintering broadly because of feelings of financial or ‘economic insecurity’: an issue that cuts across the ideological spectrum and matters also for 2024 Labour voters who are currently undecided. Second, we show that a portion of Labour losses (predominantly to Reform) is related to a person’s immigration attitudes, but is amplified by economic insecurity.

In a later section, we explain that the reason the Conservatives’ vote is continuing to split right is because of the issue of immigration, with no portion explained by economic insecurity. This might be because the Conservatives already lost votes when they were the incumbent (Green and de Geus, 2022) due to feelings of economic insecurity, leaving their remaining supporters more secure. Continued Conservative losses on immigration do not result from changes in those attitudes or evaluations but represent a pattern of continued splintering among more anti-immigration 2024 Conservatives.

Opinion polls show that the proportion thinking Labour is ‘the best party on the economy’ has fallen from 29% immediately after the 2024 General Election, to 15% in May 2025, the dates coinciding with the data shown in the vote flow figures in this report (YouGov, 2025c). Labour’s ratings on immigration have also fallen as this issue has risen in public salience.

The proportions considering Labour to be ‘best’ at handling the issue have dropped from 26% to 11% over this same period (YouGov, 2025b), while the proportions saying immigration is the ‘most important issue’ have increased from 40% to 50% (and increased further by September 2025, to 58%) (YouGov, 2025a). These polling figures do not necessarily mean that any of these relationships are causal: handling evaluations could reflect a broader decline in perceived competence across the board, and lower popularity could be driving these assessments.

There are also, of course, other potential reasons for Labour and Conservative electoral difficulties, such as leadership and unity. However, we focus in this report on the economy and immigration because of their public and political salience, and attempt to provide robust estimates of the relative importance of economic experience and immigration attitudes, both overall and on different vote choices.

To do this, we break down the way in which economic insecurity is directly influencing people’s political choices, and the indirect influence of economic insecurity via its impact on government handling evaluations and their importance for voting decisions. These represent one ‘direct’ effect of economic insecurity on Labour’s vote losses, and 3 ‘indirect effects’, which we outline in turn below.

1. Broad ‘direct effect’ of economic insecurity on Labour defections

First, we identify a clear ‘direct’ effect of feeling economically insecure on defecting from a Labour vote. Importantly, this relationship is evident across political destinations for those 2024 Labour voters on both the political left and right.

To do this, we take data from Wave 3 of our panel study (April 2025) and examine the reported economic insecurity of 2024 Labour voters within this sample. For simplicity, we take those who provided a score of 7 and above on the 0–10 economic insecurity scale to represent the ‘insecure’, and those providing a score of 0–3 as representing the ‘secure’, and we compare these 2 groups graphically. Comparing the rates of defection between secure and insecure 2024 Labour voters provides an initial window into the ‘direct effect’ of insecurity on vote choice.

Figure 8 shows that both economically secure and insecure voters have defected in large numbers from Labour since 2024, with the largest proportions opting for ‘undecided’ and then for the Greens, the Liberal Democrats and Reform UK. Overall rates of defection are higher among the insecure than the secure (58.3% vs. 46.2%). These differences are statistically significant for defections to Reform UK, the Greens, the Liberal Democrats and ‘undecided’: in Appendix Figure 20, we display the predicted probabilities of defecting from Labour by economic insecurity using a Linear Probability Model (LPM) that shows these significant effects.

Importantly, these analyses also allow us to assess whether the relationship between economic insecurity and defection holds while controlling for other factors, such as respondent demographics (income, age, education and gender) and assessments of the national economy, which we measured via respondents’ evaluations of whether Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is getting higher or lower. The relationships we report for Labour defections to the Liberal Democrats, Greens, Reform UK and undecided are robust to these additional controls.5

How many ‘lost’ voters, between July 2024 and April 2025 (coinciding with Wave 3 of our survey), might Labour have been spared, had their economically insecure former supporters instead have behaved like their more economically secure counterparts?

Figure 9 visualises this counterfactual, drawing on both the raw differences between the rates of defection among both insecure and secure 2024-era Labour supporters as well as the relative sizes of these groups as a part of Labour’s overall vote share.

While losses to the Conservatives and to abstention may have been marginally higher if the ‘insecure’ group instead behaved exactly like the ‘secure’ segment of their electorate, Labour’s overall retention rate among its 2024 General Election supporters would have been about 4 percentage points higher thanks to the cumulative effect of stemming defections to the Liberal Democrats, Greens, Reform UK, other minor parties and ‘undecided’.

The 4 percentage points saved would be equivalent to saving roughly 8% of Labour’s total vote loss between July 2024 and April 2025 (51%). These numbers would increase to 4.9 percentage points and 9.6%, respectively, if Labour supporters who were ‘neither secure nor insecure’ or undecided on their economic insecurity also had the lower defection rate of the ‘secure’ group.

We can actually interrogate these counterfactual scenarios even more robustly. Our panel data allows us to examine within-person change, such as the positive change of a respondent moving from reporting being insecure in Wave 1, to either a positive ‘secure’ category, or a middle category of neither secure nor insecure in Wave 3. It also allows us to examine those people for whom there has been no improvement or a decline in reported economic security. The latter is particularly damaging for a recently elected government, especially if hopes had been raised that things were going to get better, and if those hopes were dashed within the first year of Labour’s tenure.

Accordingly, Figure 10 presents the rates of defection from Labour — both overall and to specific parties, undecided or abstention — by April 2025 among the party’s supporters at the July 2024 General Election who: (a) moved (from March 2024 to April 2025) from being economically insecure to no longer being insecure; (b) remained not economically insecure throughout both time periods; (c) were continuously insecure in both time periods; and (d) moved from being not economically insecure into insecurity. These trajectories represent the journeys taken by 14%, 52%, 25% and 8% of Labour’s total 2024-era coalition, respectively.

Due to the relatively small samples of respondents at play, we do not distinguish between being ‘economically secure’ and being ‘neither secure nor insecure’ among our group of ‘not economically insecure’. However, logically we should still expect to see that Labour suffers progressively greater rates of defection as we move from groups (a) to (d). This would be in general accordance with the logic of reward–punish models (Tilley, Neundorf and Hobolt, 2018) in the political science subfield of ‘economic voting’. That is, voters should be liable to reward parties who preside over improvements in their welfare and punish those who preside over deteriorations.

As such, we should expect Labour voters to generally have higher rates of loyalty to the party when they are not experiencing economic insecurity, but particularly when they have experienced a recent improvement that might be perceived as linked to the actions of government. Conversely, loyalty should be lowest when voters feel insecure and especially when their transition to this state came only after the party took office.

Happily, for expectations of a (reasonably) rational electorate, this is in fact what we see. Rates of defection (including to indecision) are lowest among the group of Labour supporters that moved out of insecurity during the party’s first year in office (45%). Although it is true that rates of abandonment are only marginally higher for those who remained non-economically insecure (46%), these rates of defection are substantially lower than among 2024 Labour voters who have remained continuously insecure during Labour’s government (59%) or who actually transitioned into insecurity under Labour’s tenure (64%).

While the aggregate amount of defection presented in this figure is largely due to substantial numbers of Labour voters moving to ‘undecided’ (as highlighted in the earlier vote flow diagrams), it is notable that Labour supporters who experienced an improvement in their security show the lowest likelihood of defection to Reform UK. They are around 2.5 times less likely to defect to Nigel Farage’s party than those who remained insecure during Labour’s first year in office.

To understand the cumulative effect that improving the security of the insecure supporters or preventing others from becoming insecure might have had for Labour’s vote share, we turn to Figure 11. This again presents a visualisation of the counterfactual: how would Labour’s vote share improve if insecurity among former supporters was ameliorated or prevented from occurring?

As with Figure 9, it is based both on comparing the rates of defection among 2 groups and also their relative size as a proportion of Labour’s July 2024-era total support. Specifically, we show how many fewer losses — as a percentage of Labour’s overall April 2024 vote — would have been prevented had (a) all consistently ‘insecure’ supporters behaved like formerly 'insecure’ supporters who moved out of insecurity, and (b) had all supporters who moved into insecurity behaved like those who remained continuously non-insecure.

In counterfactual scenario (a), Labour’s vote share among its previous (July 2024) supporters would be 3.3 percentage points higher; in scenario (b), the retention rate would be a further 1.5 percentage points higher. This ‘saving’ of almost-5 percentage points in Labour’s 2024-era vote share would be equivalent to preventing almost 10% of Labour’s defections between July 2024 and April 2025 — would result from stopping losses to the Liberal Democrats, Greens and Reform, in scenario (a), and mostly by preventing losses to ‘undecided’ in scenario (b).

Accordingly, based on Figure 11, a naïve estimate of one of the benefits to Labour, had they improved feelings of economic security, would be to have prevented up to 10% of their losses during their first year in office. Of course, the actual difference could be even larger if feelings of security were maximised to the fullest, beyond the constraints of our ‘insecure’ versus ‘not insecure’ simplifications, and if insecure supporters of other parties moved towards Labour to reward the party for alleviating their financial anxiety.

However, even this conservative estimate would have substantial implications for the result at the next general election, given the increasingly competitive nature of recent local and by-elections.

In sum, our data shows that economically insecure voters are more likely to have abandoned Labour since the 2024 election. This direct effect of economic insecurity on defections from Labour remains consistent in statistical models which consider demographics and broader economic evaluations, and it is consistent across the party choice spectrum in 2025.

Taken together, these comparisons of insecure versus secure voters (a ‘between-person’ analysis) indicate that the insecure are more likely to have defected from Labour since the last election, compared to the economically secure.

As our data is a panel, which obtains responses from the same individuals on repeated occasions, we are also able conduct a ‘within-person’ analysis of the direct effect of economic insecurity. In other words, we are able to test whether 2024 Labour voters become more likely to defect from Labour as they become more economically insecure.

To do so, we estimate the average increase in the likelihood of defecting from Labour to different parties (expressed as percentages) that occurs when a person becomes more economically insecure. We calculate these effects for defections from Labour to Reform, the Greens, Lib Dems and undecided, and plot them below in Figure 12.6

This demonstrates the possible consequences for Labour of failing to address the issue of people’s feelings of economic insecurity. Additionally, estimating the effect of changes in people’s economic insecurity on their vote switching provides greater confidence that economic insecurity has a causal effect on Labour defections by ruling out alternative explanations.

Results from these models show that as 2024 Labour voters become more economically insecure, they become more likely to defect from Labour to Reform, the Lib Dems and ‘undecided’. Specifically, an increase of just under 3 points on the 0–10 economic insecurity scale is associated with an increase of 3.6 percentage points in the likelihood of defecting to Reform, an increase of 2.3 percentage points in the likelihood of defecting to the Lib Dems and an increase of 2.7 percentage points in the likelihood of defecting to ‘undecided’.

Among 2024 Labour voters in our survey who participated in 2 or more waves, 25.6% experienced a change of 3 or more points on the economic insecurity 0–10 scale on at least one occasion. This shows that the changes in economic insecurity represented in Figure 12 are not rare instances but instead a frequent experience among Labour voters, with potentially far-reaching political consequences. Taken together, this evidence highlights the importance of addressing economic insecurity if Labour are to stem its tide of defections since the 2024 election.

2. ‘Indirect effect’ of economic insecurity on Labour’s handling of national economy

As explained in the introduction, the electoral importance of ‘the economy’ is not only via a person’s own economic circumstances and their worries or their lack of worries about those circumstances. It is also about the national economy as a signal of government competence and whether things are going in the right direction (Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier, 2019). That is helpful information because it gives voters greater, or lesser, confidence in the Government overall and provides a competence signal that transfers to other policy issues (Green and Jennings, 2017), while a growing economy makes fiscal and spending decisions easier.

The association between evaluations of a government’s handling of the national economy tends to be strongly related to vote choice. Indeed, for the defections that have taken place between 2024 and 2025 for Labour, we find in our statistical analysis that evaluations of Labour’s handling of the national economy have a substantial effect on defections to all destinations (see Table 6 in the Appendix), independent of economic insecurity. Put differently, perceptions of how Labour is handling the economy are very important for its electoral prospects, alongside people’s experiences and feelings of economic insecurity.

Critically, these experiences and evaluations of the national economy are interlinked. Among those respondents in our sample who are economically insecure, ratings of Labour’s handling of the national economy are significantly more negative. This can be seen in Figure 13, which shows the relationship between economic insecurity and evaluations of Labour’s handling of the economy. Specifically, we plot the percentage of insecure and secure respondents at each wave who evaluate Labour’s handling of the economy as ‘Very Bad’ (the most negative category) at Waves 2 and 3 of the JRF survey (October 2024 and April 2025).

This comparison shows that insecure respondents are more likely to evaluate Labour’s performance as negative. At Wave 2, 40.1% of insecure respondents evaluate Labour’s handling of the economy as ‘Very Bad’, while only 22.8% of the economically secure do so — a gap of 17.3 percentage points. At Wave 3, the gap between the insecure and secure is similarly sized, at 17.7 percentage points.

Next, in Figure 14, we again plot the percentage of respondents who evaluate Labour’s handling of the national economy as ‘Very Bad’, but this time break the sample down by whether respondents were Labour voters in 2024 or voted for other parties in 2024.

As the plot shows, 2024 Labour voters are less likely to evaluate Labour’s economic performance as negative, but the gap between the secure and insecure remains. Specifically, at Wave 2, 18.2% of insecure Labour voters evaluated the Government’s handling of the economy as ‘Very Bad’ — 12.4 percentage points more than economically secure Labour voters. At Wave 3, the equivalent figure was 22.8%, compared to only 10.3% of economically secure Labour voters, representing a 12.5 percentage point gap.

While these figures represent simple percentages, statistical analysis suggests to us that the association between economic insecurity and evaluations of Labour’s handling of the national economy is very likely causal, and that insecurity leads to more negative handling evaluations rather than the other way round. We derive this conclusion in 3 ways.

First, we note that the relationship between economic insecurity and evaluations of Labour’s handling of the national economy holds for people who voted Labour in 2024, and those who did not, and so is not reducible to partisan effects. Labour’s 2024 voters rate Labour less negatively overall, but the distinctions between the insecure and secure persist.

Second, we find evidence that economic insecurity is associated with economic handling evaluations at the within-person level, which provides stronger evidence that this relationship is causal (see Table 5 in the Appendix).

Third, we assess the direction of these assessments in a full panel model from an earlier period, and these confirm that economic insecurity leads to negative assessments of handling of the national economy more strongly than vice versa.

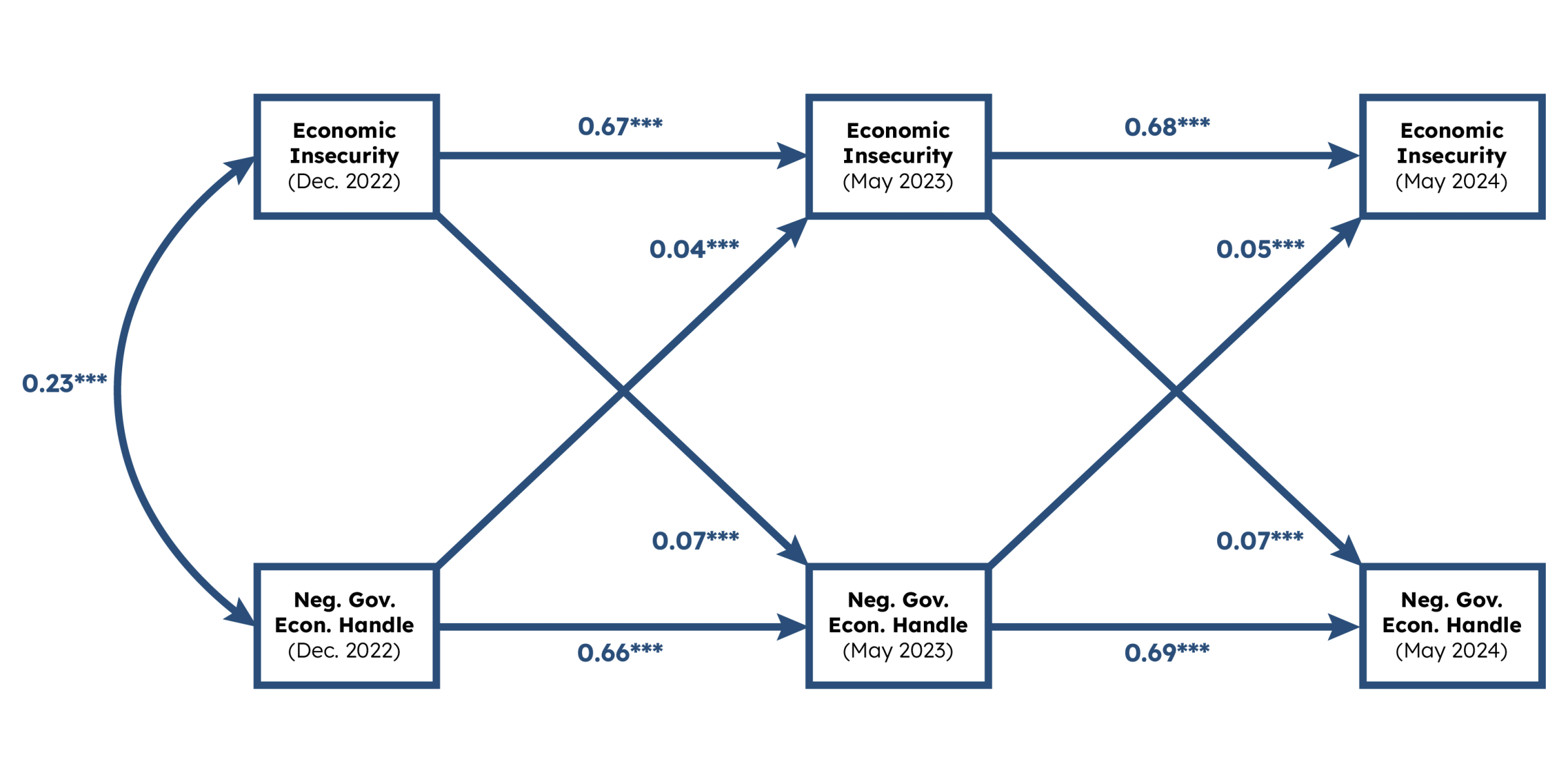

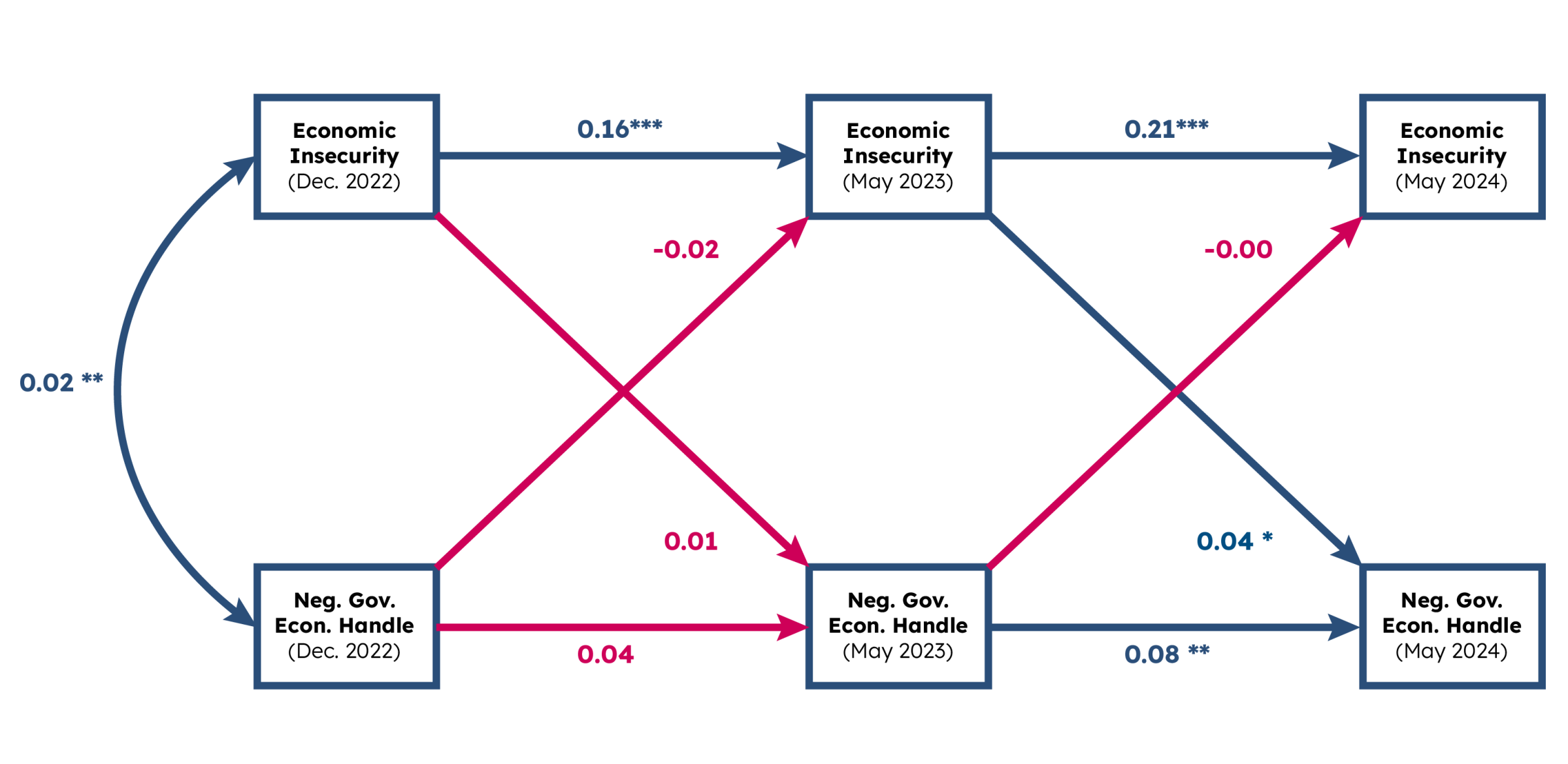

We can only run these analyses where both are measured over 3 or more waves of a survey, and this was only true for the British Election Study panel, in month-years December 2022, May 2023 and May 2024, and therefore the handling evaluations relate to the Conservative Government’s handling of the economy. We report the path diagrams in Appendix Figure 21, which shows the statistical relationships between a person’s economic insecurity and their evaluations of the Government’s handling of the economy at the subsequent wave, along with the reverse relationship (that is, the relationship between government handling evaluations and insecurity at the subsequent wave).

Comparing these ‘cross-lagged’ effects allows us to test whether it is economic insecurity that is driving changes in economic handling evaluations, or vice versa. Conducting this comparison, we do not find that assessments of the handling of the national economy lead to changes in feelings of economic insecurity, but we do find that experiences and feelings of economic insecurity have some subsequent effect on evaluations of handling of the national economy.

This provides evidence that economic insecurity is ‘causally prior’ to evaluations of government performance on the economy. In other words, when people become economically insecure, this insecurity subsequently prompts them to evaluate government economic performance as more negative — not the other way round.

3. Economic insecurity amplifies the impact of Labour's handling of the national economy on Labour defections

The measurement of economic insecurity gives us an insight into people’s worries. This is a particularly powerful concept because a person’s worries will make them attentive and responsive to other signals (Albertson and Gadarian, 2015), heightening their awareness and their need for other aspects of the economy, or immigration, to be handled better.

We anticipate that economic insecurity will amplify the relationship between evaluations of Labour’s handling of the economy and the tendency to defect from Labour. When people are worried about their household finances, we expect that they will pay greater care and attention to government handling of the national economy, because evidence shows that worry prompts people to seek out information (Bonifai, Malesky and Rudra, 2024; Valentino et al., 2008).

Second, feelings of economic insecurity likely raise the salience or importance of the economy to an individual, which means that the insecure will place greater emphasis on economic concerns when choosing who to vote for, as previous academic studies would suggest (Fournier et al., 2003; Green and Hobolt, 2008). These consequences of economic insecurity, we argue, will increase the likelihood that people who evaluate Labour’s handling of the national economy ‘punish’ the Government by defecting to other parties, an ‘indirect effect’.

Our analysis supports this argument. In statistical tests, we identify an indirect effect of economic insecurity on how important Labour’s handling of the national economy is to different individuals and their tendency to defect from Labour. Put differently, we find that economically insecure individuals are more likely to defect from Labour when they evaluate Labour’s economic handling as negative and, again, we find this effect is a broad one for defections to the left and right.

To test this ‘indirect effect’, we combine measures of economic insecurity and Labour’s handling of the national economy into a multiplicative ‘interaction’ term (that is, the individual-specific product of economic insecurity and economic handling scores),7 which allows us to assess whether people who are insecure are more likely to defect from Labour on the basis of their rating of Labour’s handling of the national economy than people who are economically secure.

Figure 15 displays ‘average marginal effects’ (AMEs), which are the average difference in the likelihood of defecting from Labour to different parties (expressed as percentages) between a person who evaluates Labour’s handling of the economy as negative, and one who evaluates it as more positive. Specifically, we calculate the difference in the likelihood of Labour defection associated with a difference of just under 1 point on the 5-point economic handling scale (for example, between a person who evaluates Labour’s economic handling as ‘Fairly Bad’ and one who evaluates it as ‘Very Bad’).8

Importantly, we calculate these effects for both economically secure and economically insecure voters, which allows us to compare the 2 groups. Each plot in Figure 15 is labelled with the difference between the ‘average marginal effects’ for economically secure and insecure individuals. If a difference is denoted with an asterisk, the difference is statistically meaningful, and the greater the number of asterisks, the stronger the difference.

This shows that, among 2024 Labour voters, those who evaluate the Labour Government’s handling of the national economy as negative are significantly more likely to defect to Reform UK, the Greens and the Liberal Democrats when they are economically insecure. The difference between the secure and insecure for Reform defections is 5.8 percentage points; for the Greens, it is 3.5 percentage points, and for the Lib Dems, it is 2.9.

These differences remain significant for Reform, Green and Lib Dem party defections with additional statistical controls added to the model, as we show in section A3 of the Appendix. Economic insecurity therefore has a significant and broad indirect effect on voting via its amplification of concerns about Labour’s handling of the economy, and it makes people hold more negative evaluations of Labour’s handling of the economy.

Additionally, for Reform, Greens and ‘undecided’, we find evidence of a within-person effect of negative evaluations of Labour’s handling of the economy on defections among the economically insecure, but not among the secure. In other words, as economically insecure individuals become more negative about Labour’s handling of the economy, they become more likely to defect. This provides more robust evidence for the indirect effect of insecurity on voting behaviour and further emphasises that Labour can provide a buffer against negative assessments of national economic performance if it takes further steps to address individual and household economic insecurity.

4. Economic insecurity amplifies the impact of Labour's handling of immigration on Labour defections