The economic circumstances of cohorts born between the 1940s and the 1970s

Profound economic and social changes mean that people born at different times face radically different economic environments

Due to sustained economic growth in the post-war period, many assume that successive generations will be better off than the last. But is this true?

This study:

- Uses household survey data collected over the last 50 years to look at the incomes, wealth and expected inheritances of those born between 1940 and 1980. It explores the likely economic position of the younger cohorts in later life, in absolute terms and relative to their predecessors.

- Looks at how equality has changed during the second half of the 20th century, and the impact both collectively and on individuals’ typical circumstances.

- Considers the impact of the rapid switch away from defined benefit (final salary) pension plans towards typically less generous defined contribution plans in the private sector, and changes in home ownership and inheritance patterns.

The full report is available at https://ifs.org.uk/sites/default/files/output_url_files/r89.pdf

Summary

Key points

- Working-age adults do not currently have higher incomes (after adjusting for inflation) than their predecessors born 10 years earlier had at the same age. For example, 40-year-olds now have no higher incomes than 40-year-olds a decade ago.

- Those born in the 1960s and 1970s did have higher incomes during early adulthood than their predecessors, but this additional income was spent: they have not saved any more past income than their predecessors had by the same stage in life.

- Under current policy plans (including the single-tier pension), state pension entitlements for these individuals will tend to replace a smaller proportion of previous earnings than is the case for those currently above, or around, the state pension age.

- The rapid switch away from defined benefit (final salary) pension plans towards typically less generous defined contribution plans in the private sector will have affected younger cohorts significantly more than older ones.

- Individuals born in the 1970s are taking longer than their predecessors to get on the housing ladder, and their homeownership rate has stalled over the last few years at around two-thirds – far below the four-fifths rate at which it peaked for those born in the 1940s and 1950s.

- If people’s expectations are correct, then receipt of inheritances will be far higher among those born in the 1960s and the 1970s than among those born earlier. Twenty eight per cent of those born in the early 1940s have received or expect to receive an inheritance, compared to 70 per cent of those born in the late 1970s; but expected inheritances are distributed unequally and are higher for those who are already wealthier.

BACKGROUND

Changes in the economy and society mean that individuals born at different times can face radically different economic environments. Due to sustained economic growth in the post-war period, we have become used to seeing successive birth cohorts better off than the last. A rapid rise in income inequality during the 1980s means that people old enough to have spent much of life in a pre-1980s environment would have started out as a far more equal group than subsequent cohorts. There have also been major changes in demographics, government policy and the way that we plan and save for retirement. This study compared and contrasted the economic circumstances of those born between the 1940s and the 1970s, currently aged between their mid-30s and mid-70s, using several decades of data on income, wealth and inheritances from large-scale household surveys.

Incomes and saving

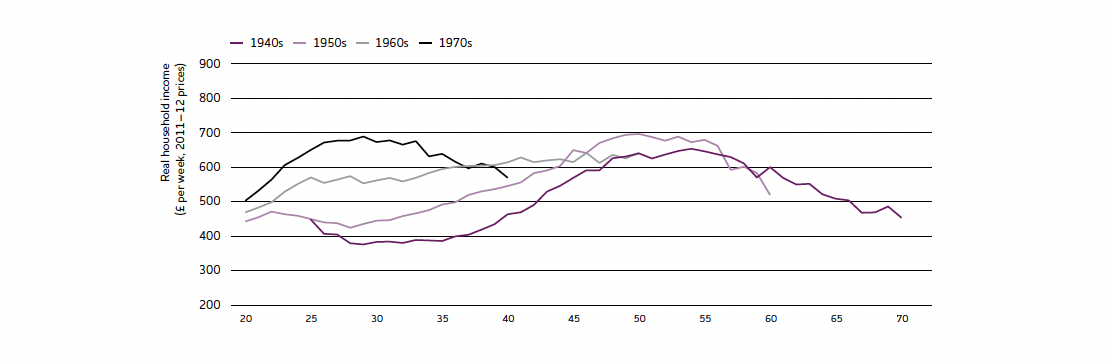

There has been a lack of household income growth for the working-age population over the past decade. As a result, the 1960s and 1970s cohorts have not been experiencing the rapid rise in income between the ages of 30 and 50 that their predecessors did; and younger cohorts do not have higher income than those born 10 years earlier had at the same age, as shown by Figure 1, below. This pattern holds across most of the income distribution.

Figure 1 – Equivalised household median income by age and birth cohort

Figure 1 also shows that for much of their earlier adulthood, the 1960s and 1970s cohorts did have higher take-home incomes than prior cohorts had at the same age. For example, at the age of 30, real median income was 20 per cent higher for the 1970s cohort than for the 1960s cohort, 52 per cent higher than for the 1950s cohort and 77 per cent higher than for the 1940s cohort. However, these income differences between birth cohorts at younger ages were (at least) matched by differences in spending. As a result, the 1960s and 1970s cohorts had higher living standards during early adulthood than their predecessors had, but they have not actively saved more take-home income than their predecessors had by the same stage in life.

The large rise in income inequality during the 1980s meant that, while incomes in early adulthood were higher for those born in the 1960s and 1970s than for their predecessors, they were also significantly more unequal.

Wealth and assets

The most important sources of wealth for individuals at or around retirement are state pensions, private pensions and property. The study therefore analysed how those born in the 1960s and 1970s compare to their predecessors with respect to these components of wealth.

Under current policy, state pension entitlements for individuals born in the 1960s and 1970s will tend to replace a smaller proportion of prior earnings than is the case for those currently above, or around, the state pension age. However, this difference across cohorts is smaller for low earners and for those who have spent time out of work caring for children. As a result, state pensions may have a more equalising effect on the retirement incomes of younger cohorts than for their predecessors.

Membership rates in private pension schemes have changed little overall for cohorts born between the 1950s and 1970s, masking a significant decline among men offset by a rise among women.

However, the nature of these schemes has changed dramatically, with a rapid switch away from occupational defined benefit pension plans towards less generous defined contribution plans in the private sector. This will have affected younger cohorts more than older ones.

Individuals born in the 1970s are taking longer than their predecessors to get on the housing ladder. Sixty six per cent of individuals born between 1970 and 1976 owned a home at age 35, compared to 71 per cent of those born in the 1950s and 1960s. In recent years, the homeownership rate among the 1970s cohort appears to have stopped rising altogether, remaining at around two-thirds – far below the 80 per cent rate at which it peaked for those born in the 1940s and 1950s. However, the proportion of individuals born in the 1970s who own homes outright (i.e. without mortgage debt) is as high as it was for previous cohorts at the same age, despite the decline in overall homeownership. This is tentative evidence that property wealth is less equally distributed among the 1960s and 1970s cohorts than it was among the 1940s and 1950s cohorts at the same age.

Inheritances

Taking account of inheritances is particularly important when comparing the economic circumstances of different cohorts, as most inheritances are transferred from one generation to the next.

If people’s expectations are correct, then the number in younger cohorts who will receive an inheritance is far larger than the number in older cohorts who have done (or will do) so. Twenty eight per cent of people born in the early 1940s and 70 per cent of those born in the late 1970s have received, or expect to receive, an inheritance.

Individuals are more likely to expect inheritances – and to expect large inheritances – if they already have relatively high net wealth. Of the 30–34 age group in 2006–08 (born between 1972 and 1978), 78 per cent of the wealthiest third and 45 per cent of the least wealthy third expected a future inheritance, while 35 per cent of the wealthiest third and 12 per cent of the least wealthy third expected a future inheritance worth at least £100,000. Expected future inheritances also tend to be concentrated within the same households – individuals expecting inheritances are far more likely to have partners who also expect them.

Conclusion

Inheritances look like the major potential reason why the later economic position of cohorts born in the 1960s and 1970s could yet turn out better than that of their predecessors, on average. In combination with the lack of positive signs with respect to other economic indicators, this suggests that the economic fate of the 1960s and 1970s cohorts may be relatively dependent on the fortunes of their parents. But the prevalence and value of expected future inheritances are distributed unequally, with households that are already relatively wealthy far more likely to benefit. The end result could be growing inequality within younger generations – rather than between older and younger ones.

About the project

The study used a number of different micro datasets based on large household surveys to explore the changing economic circumstances of different cohorts. The Family Expenditure Survey (FES) and its subsequent incarnations provided a consistent measure of household incomes and expenditures from 1974 to 2011. When looking at home ownership, which is also recorded in the FES, the study used the Family Resources Survey from 1994–95 onwards due to its larger sample size. The General Household Survey provided a measure of active membership in private pension schemes from 1972 onwards. The study used data from the first two waves of the Wealth and Assets Survey (collected between 2006 and 2010) to look at wealth holdings, expected future inheritances, and inheritances received for each birth cohort.

This report is part of the savings, debt and assets topic.

Find out more about our work in this area.