Public attitudes to economic inequality

A review of public attitudes to economic inequality, poverty and redistribution.

Economic inequality in the UK stands at historically high levels and there is emerging evidence that a high level of inequality may cause socio-economic problems. However, little is known about public attitudes on this issue. The study:

- starts by examining public attitudes to inequality and poverty;

- considers public attitudes to redistribution;

- highlights apparent contradictions in public attitudes;

- explores the more underlying values people draw on when forming their opinions on these issues

- reviews key findings, and discusses policy implications and research gaps.

Summary

Economic inequality – the unequal distribution of financial resources within the population – is now a marked feature of the socio-economic structure of the UK. However, relatively little is known about public attitudes on this issue. This study examines public attitudes to economic inequality, and related issues of poverty and redistribution.

Key points

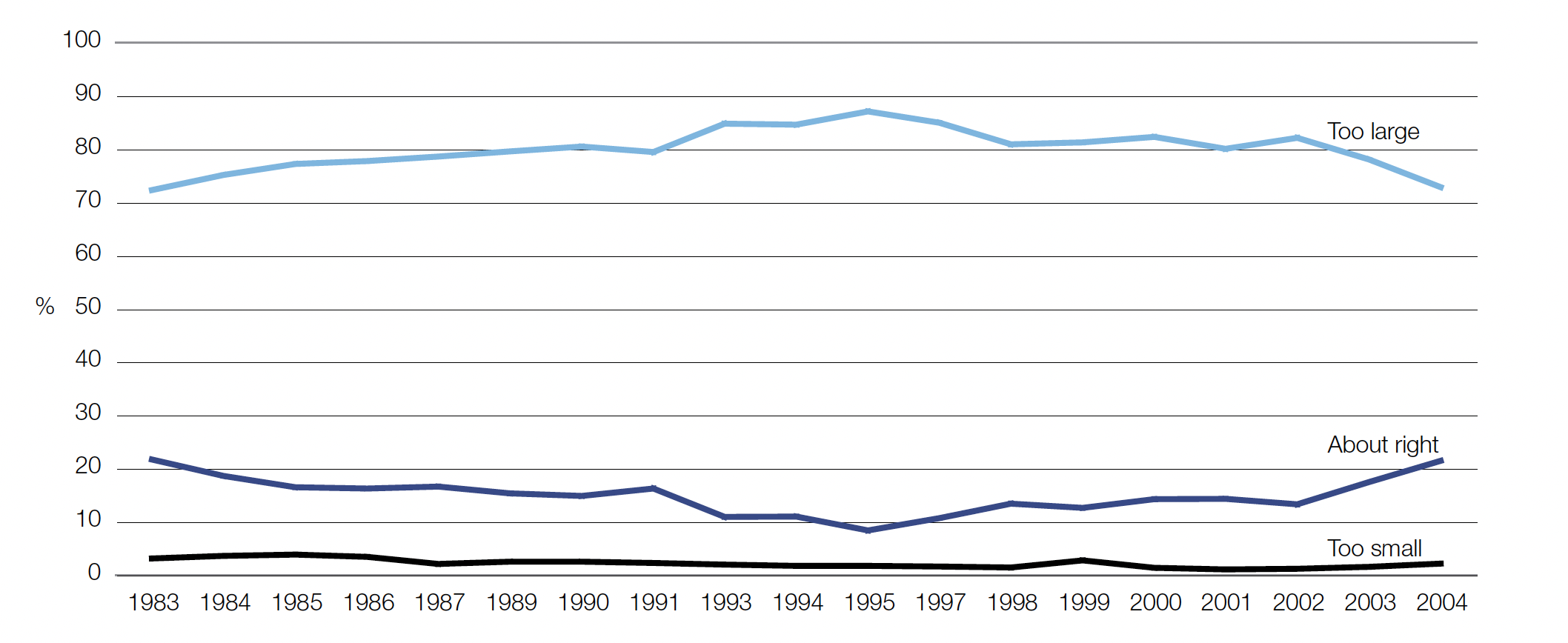

- Over the last 20 years, a large and enduring majority of people (73 per cent in 2004) have considered the gap between high and low incomes too large.

- People do not necessarily think that those on low incomes are underpaid, but that those on higher incomes are very overpaid.

- Public attitudes to redistribution are complex, ambiguous and apparently contradictory. Current evidence does not explain why a smaller proportion of people support redistribution than see the income gap as too large.

- People's beliefs about the roles of luck and effort in determining individual success can affect their attitudes to inequality, poverty and redistribution.

- In 2006, 55 per cent of people thought there was 'quite a lot' of poverty in Britain. Only 13 per cent thought it would fall in the next 10 years.

- The authors conclude that:

- economic inequality should be the focus of far greater policy attention;

- knowledge is limited on several relevant issues – future research needs to take a more sophisticated approach to talking about 'inequality' and 'redistribution', as these can take different forms.

- future research also needs to focus more on people's underlying values, and the discourses they draw on.

Background

Economic inequality has become a striking feature of the UK's socio-economic structure. Income inequality stands at historically high levels, and asset inequality has increased since the 1990s, with the top 1 per cent now owning nearly a quarter of all marketable assets.

Inequality and poverty are closely related, but inequality is also a distinct phenomenon. There is growing interest in economic inequality, and evidence that a high level of inequality may cause socio-economic problems.

The Labour government has displayed concern with some forms of inequality but its position regarding economic inequality is somewhat ambiguous. It has focused more on tackling equality of opportunity rather than equality of outcome.

This study has been carried out because relatively little is known about public attitudes to inequality and redistribution.

Public attitudes to economic inequality

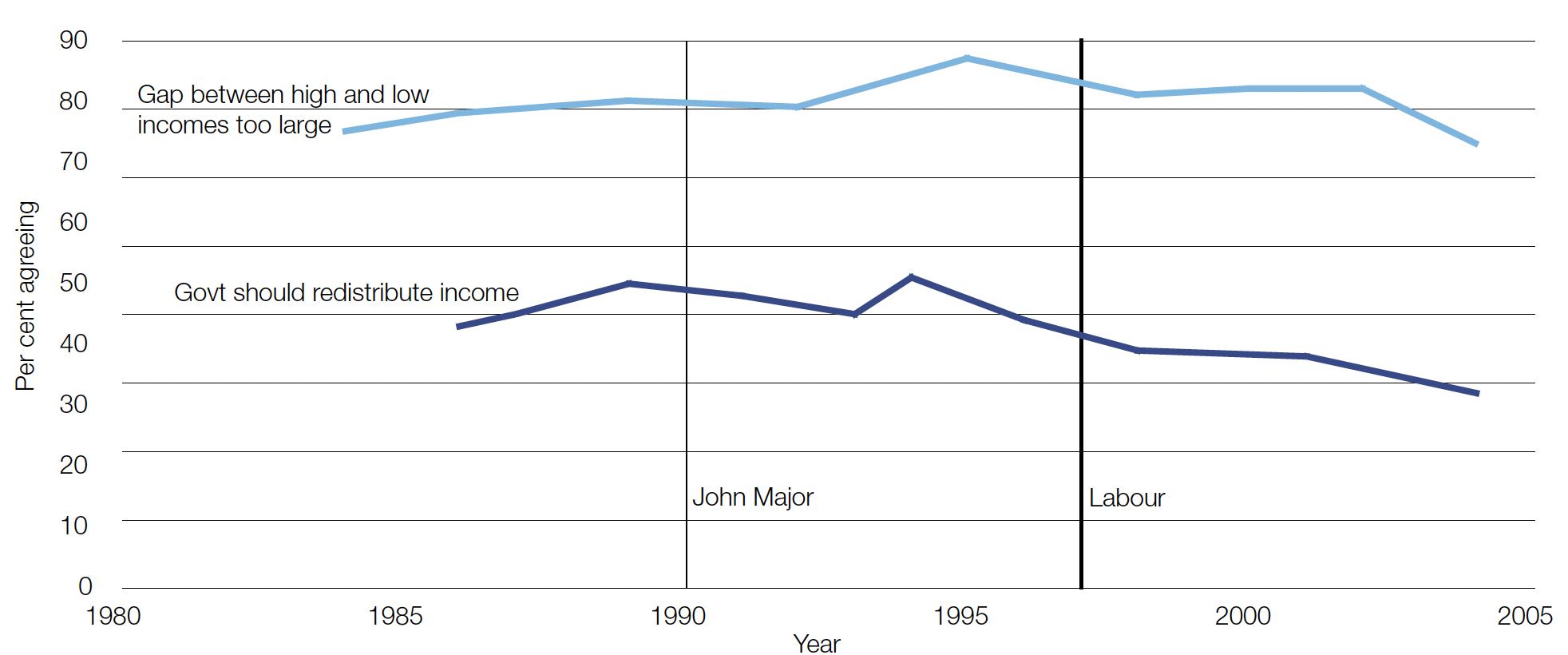

Over the last 20 years, a large and enduring majority of people have considered the gap between those with high and low incomes too large – a view held by 73 per cent of people in 2004.

In particular:

- Clear majorities in all groups think that the income gap is too great, but some socio-economic groups – principally those on higher incomes – are significantly less likely than others to believe this.

- There is widespread acceptance that some occupations should be paid more than others: but the gap between high and low-paid occupations is far greater than people think it should be; and the actual gap is far greater than people consider appropriate.

- People do not necessarily think that those on low incomes are underpaid, but that those on higher incomes are very overpaid.

- People's knowledge about inequality is limited.

- Public attitudes should not be seen as fixed but as more fluid with potential for change. However, the literature reviewed by the authors does not provide any clear explanation of why attitudes change over time.

- In 2006, a majority of people (55 per cent) thought there was quite a lot of poverty in Britain, only 19 per cent thought poverty had fallen over the last decade, and close to half (46 per cent) thought poverty would increase over the next ten years. Only 13 per cent thought it would fall.

- There is a shortage of knowledge regarding how people interpret and understand issues relating to inequality and poverty.

Figure 1: People's views of whether the income gap is too large/about right/too small (1983-2004)

Figure 2: Views about the income gap and support for redistribution

Public attitudes to redistribution

Public attitudes to redistribution are complex, ambiguous and apparently contradictory. The study found that:

- Far more people think the income gap is too large than explicitly support the principle of redistribution. This could be because people do not feel particularly strongly about inequality or because they favour other kinds of policies rather than direct redistribution, but current evidence is unable to explain this.

- A third of the public (32 per cent) in 2004 agreed that 'government should redistribute income from the better-off to those who are less well-off'. This is much lower than in 1996 (44 per cent) despite the fact that levels of actual income inequality have changed little over that time.

- There is evidence, however, of support for redistributive policies in practice:

- Sixty-two per cent of people in 2004 favoured a combination of tax and benefit approaches that are moderately or strongly redistributive.

- Thirty-eight per cent of people in 2004 said the government is doing too little or much too little to redistribute income from the better-off to those who are less well-off. Twenty-eight per cent said it was doing about the right amount and only 13 per cent said it was doing too much.

- People have limited knowledge of the tax system, and its redistributive impact.

- Large majorities support extra taxes to pay for health and education but there is also concern that taxes are both too high in general and too high for individual respondents in particular.

- There is a general view that the low-paid pay too much in tax and the highly-paid pay too little but there is no agreement about what constitutes low or high pay.

As with inequality and poverty, there is a lack of knowledge about how people interpret and understand issues relating to redistribution.

Explaining public attitudes to inequality and redistribution

The free personal care policy is perceived to have benefited many older people with care needs, but also to have either directly or indirectly disadvantaged certain groups of people, such as the under 65s. It is widely regarded as inequitable and discriminatory in limiting eligibility to those with care needs aged 65 and over. Budgetary constraints experienced by authorities are seen as limiting further community care service development for other client groups.

Recent evidence on public opinion (2005 Scottish Social Attitudes Survey) shows that 59 per cent of Scots believe that personal care should be paid for by government, and 68 per cent would pay an extra penny in the pound in income tax to finance spending on personal care.

The impact on local authorities

There is continuing variation at a significant level between local authorities, and developments are inconsistent across the country, with some authorities apparently increasing overspends and others controlling expenditure more successfully.

The particular situation in each local authority depends on a culmination of previous decisions on care policies. Before free personal care, authorities had a variety of different ways of charging for care. Under the free personal care policy, authorities faced new expenditure. The impact of this varied according to previous charging practices. For example, where authorities had not previously charged for personal care, the financial impact of the policy was not large. Elsewhere, many older people previously charged for care-related services are now entitled to free personal care. This affects the balance of funding local authorities receive.

Nearly all local authorities report that they are under-funded for the delivery of free personal care. They welcome the fact that evidence of numbers receiving personal care is now emerging. Prior to the introduction of free personal care, personal care was not distinguished in data collected by local authorities and the Scottish Executive, and therefore its costs could not be ascertained.

Nevertheless, variations in spending now provide evidence that some local authorities have had more success than others in controlling expenditure. Indicators also show that the highest spenders do not necessarily provide the best quality services. There is evidence that whole system reform at local authority level can contribute to success in this area.

There are large differences between local authorities in expenditure on delivering care at home.

Key conclusions and implications

In the light of the contradictions in public attitudes to inequality and redistribution, examining the more underlying values people draw on offers a potential way forward, and is a more powerful way of explaining attitudes than demographic and socio-economic variables, such as age and income. In more detail:

- Analyses that have focused on values have divided the population in different ways, for example: 'Samaritans' (30 per cent of the population – those most in favour of redistribution and a strong welfare state); 'Club members' (45 per cent of the population – they support a more conditional welfare state); 'Robinson Crusoe's' (25 per cent of the population – they prefer to emphasise self-reliance and are more resistant to redistribution).

- Beliefs about the respective roles of luck and effort in determining individual success affect attitudes to inequality, poverty and redistribution. For example, those who believe that hard work leads to success are less supportive of redistribution.

- There is, however, little direct empirical evidence about public attitudes regarding the causes and justice/injustice of inequality. But we do know that only 17 per cent of people believe that large differences in income are necessary for Britain's prosperity, whereas 58 per cent believe that inequality persists because it benefits the rich and powerful.

- Sociological theory has highlighted the importance of a number of debates in relation to attitudes to inequality and redistribution. These debates include: the role of self-interest versus altruism and public values; reference groups and relative deprivation; and empathy and socio-cultural distance.

Conclusion

Economic inequality should be the focus of far greater policy attention. There is growing interest in the potential effect of economic inequality on society, and emerging evidence that a high level of inequality may cause socio-economic problems.

There is considerable public concern regarding economic inequality, and certainly no evidence that people see the income gap in the UK positively. There is also public concern with the position of those on high earnings. But attitudes are highly complex and apparently contradictory.

What is clear is that the available knowledge on several relevant issues is very limited. Future research needs to take a more sophisticated approach to talking about 'inequality' and 'redistribution' as these vary in form, and attitudes may similarly vary depending on the particular kind of inequality or redistribution that people have in mind. Future research also needs to focus more on people's underlying values, and the discourses they draw on.

About the project

The project was undertaken by Michael Orton at the Institute for Employment Research, University of Warwick, and Karen Rowlingson, Institute of Applied Social Studies, University of Birmingham.

The study was based on an extensive literature search and consultations with over 20 experts in this field.

This report is part of the public attitudes topic.

Find out more about our work in this area.