Meeting the moment

A toolkit to help Scottish political parties shape their thinking and action to meet the 2030/31 child poverty reduction targets ahead of the 2026 Scottish Election.

- Executive summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. How is child poverty measured?

- 3. How we built this toolkit

- 4. Meeting the moment in the labour market

- 5. Meeting the moment with the social security system

- 6. Housing emergency

- 7. Combined modelling packages

- 8. Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Acknowledgements

- How to cite this report

- Executive summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. How is child poverty measured?

- 3. How we built this toolkit

- 4. Meeting the moment in the labour market

- 5. Meeting the moment with the social security system

- 6. Housing emergency

- 7. Combined modelling packages

- 8. Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Acknowledgements

- How to cite this report

Executive summary

This document is intended as a toolkit for all parties standing in next year’s Scottish Parliament elections to ensure their manifestos are up to the task of meeting the child poverty reduction targets. It is also an accountability tool for voters and journalists to use when parties outline their plans to reduce child poverty. We show a high bar of action needed, with all parties needing to rise to the challenge and meet the moment.

The toolkit provides a variety of policy tools and tests their impact. It builds from individually modelled scenarios and policy solutions (including over 20 different options), that increase incomes from work and social security, to 3 scenarios that look at the cost and poverty reduction impact of combined policy interventions. In providing these combined scenarios, we are not attempting to prescribe what each party should do, just the extent of action that will be needed. But we think the combined scenarios should provide both hope and determination to make the big changes in our society that are needed to meet these targets.

The challenge is tougher than it should be due to the interim child poverty reduction targets having been missed. They have, however, been missed in the context of child poverty in Scotland being broadly stable, although there is a growing divergence of poverty rates between Scotland and the rest of the UK, where they are predicted to rise (Milne et al., 2025). This underlines both that poverty is not inevitable and that decisions made in Holyrood make a difference.

Key findings

We have used the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) Tax-Benefit Model to produce these findings. They are based on the baseline assumption that, without further action, relative child poverty is 19% in 2030/31. It includes current policies and uprates benefits and tax thresholds by inflation where expected. It does not, unless specified, include the announced mitigation of the two-child limit in Scotland, which is due to be introduced in 2026.

- Combining efforts on work and social security interventions could reduce child poverty to 10% by the end of the next Parliament. This would cost an additional £920 million in targeted child benefits in Scotland, as well as significant additional costs associated with raising employment. It would also increase tax revenues by £410 million due to increased parental employment, as well as reducing Universal Credit expenditure by around £500 million.

- Moving parents into work and into more hours of work has a significant impact on reducing child poverty. It is expected to bring the child poverty rate down to 14% and lift 60,000 children out of poverty in 2030/31. However, this will require moving over 50,000 parents into work as well as increasing the hours of 20,000 parents.

- A Scottish Child Payment (SCP) of £40 has the best poverty reduction impact per pound for each depth of poverty. This would require an additional £190 million a year. However, on its own, it only brings the child poverty rate down to 18%.

- Increasing SCP take-up to 100% at the current rate could reduce child poverty by up to 10,000 children. This would increase current costs by £70 million a year by 2030/31.

- Boosting the SCP for households with a baby, a single parent or with a disability to include an additional SCP payment every week at the current rate would lift around 10,000 children out of poverty and cost £310 million in 2030/31. While this seems like a comparatively small fall in the poverty rate for the cost, many of these families are in deeper poverty, so while it would lift their incomes, it would not push them above the poverty line. We also see big falls in deep and very deep poverty in this scenario.

As we note, we have deliberately not prescribed an exact course of action in this work. Instead, we have shown the required scale of action needed and the areas of policy that will, in all likelihood, be the most important. This enables parties to mould their approach according to their values and priorities. However, the evidence is unequivocal: we need greater investment in social security, together with a paradigm shift in how we support people to reach their potential in the labour market.

The challenge to the next parliament is plain: lift around 100,000 children out of poverty. To do this, we must take the progress made so far and raise the bar. This will require a laser-focused prioritisation, but the alternative is the status quo. The current statutory child poverty delivery plans provide templates for how to tweak around the edges of the status quo, but the next government must go much further.

Furthermore, there is no free way to meet these targets. We have provided costings for the social security policies we have modelled and illustrative ones for the type of employment support needed. We are also, however, able to show the possible increase in tax revenue generated by the modelled labour market outcomes as well as the falls in other benefit spend (on Universal Credit in particular). While this will not offset the upfront costs to the Scottish Government, it does show that efforts to improve people’s access to work will have positive impacts on tax revenues (as well as reducing demand for means-tested benefits).

In any event, we argue that to realise this potential in the labour market, the social security system needs to be scored as a genuine investment, either to steady households as they prepare to enter the labour market or to get closer to some semblance of income adequacy that is absent from the existing settlement.

Every candidate, manifesto writer and party member should reflect on the words of former First Minister, Donald Dewar, in his speech at the opening of the Scottish Parliament, and take on his challenge:

We are fallible. We will make mistakes. But we will never lose sight of what brought us here, the striving to do right by the people of Scotland; to respect their priorities; to better their lot; and to contribute to the commonwealth.

I look forward to the days ahead when this Chamber will sound with debate, argument and passion. When men and women from all over Scotland will meet to work together for a future built from the first principles of social justice.

This is a huge opportunity for those asking the public to vote for them in 2026, a chance to do things differently, a chance to go to the public with an offer of generational significance – one that will change what it means to grow up in Scotland.

1. Introduction

There are 240,000 children in poverty in Scotland.

Every one of them is a reason for all political parties to deliver a better Scotland. The election in May 2026 is the time for our politicians to set out their story for Scotland’s future. That future has to be one in which the Scottish Parliament’s child poverty reduction targets are met. It would be one where every child has the nurturing, fun and loving childhood that they all deserve.

The Scottish Parliament has undoubtedly brought new political engagement and ideas to Scotland, but its next term will be a big test. With global instability and extremism on the rise at home and abroad, Holyrood has the chance to show how things can be different, and to show how people’s futures can be brighter due to bold and purposeful action by government and those we elect to represent us.

It is that future that politicians should always have in their minds. It relies upon us realising the potential of our next generations. Child poverty robs individual children, and us all, of that prosperity. Meeting the child poverty reduction targets would radically improve our society and economy and, most importantly, rid the anxiety and insecurity that so many children currently face in Scotland.

There is much hand-wringing (often from the politicians themselves) on the breakdown of trust between the state and citizens, but the truth is that too many people feel left behind and overlooked. Meeting these targets is an opportunity to rebuild that trust and to do so in a way that changes what it means to grow up in Scotland. This is a pivotal moment in Scotland.

2. How is child poverty measured?

The headline measure of child poverty in the Child Poverty (Scotland) Act 2017 is relative poverty after housing costs. This is the most common measure used when discussing poverty in Scotland as well as in the rest of the UK. This measure shows whether the incomes of poorer households are catching up with average incomes or are being left behind.

People are in relative poverty if they live in a household where the income is below 60% of the UK median income after their housing is paid for. The line is also different depending on the type of household people live in – put simply, the more people that live in a household, the more money they will need to maintain the same standard of living as a smaller household.

As a result, the poverty line is adjusted depending on household size and composition. This allows a more realistic assessment of a household’s income and enables comparisons of household incomes across different families.1

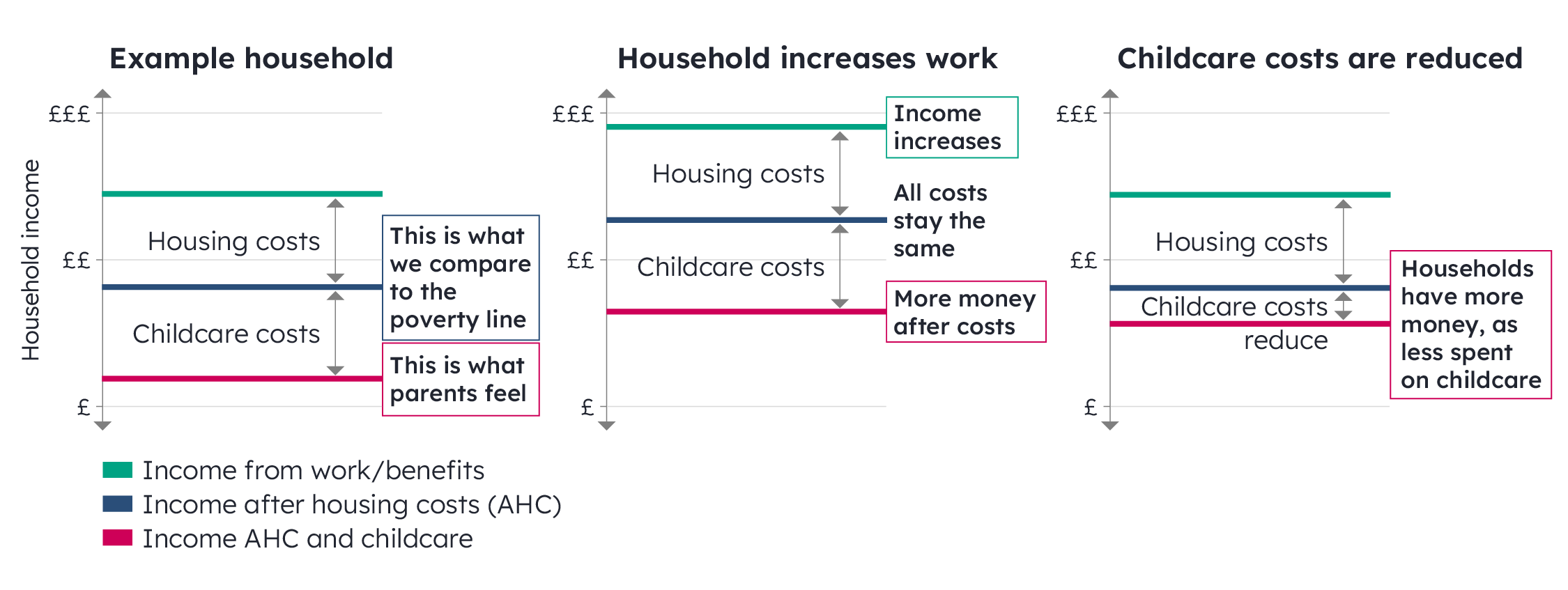

It is important to note that the only cost that is included in this measure of poverty is housing costs, so reducing other costs that a family might face will have no impact on their distance from the poverty line, although by reducing costs we would increase their remaining income available to spend on other items.

What does this look like for a family?

Here we show an example family that illustrates how income from work, benefits, housing costs and family composition all play a part in how close/far a family is from the poverty line.

Calum and Mia have a 10-month-old baby called Jess. They live in a private rented flat in Fife (2 beds). Calum is paid the real Living Wage (rLW) and works full-time, but Mia is currently not in work as she is caring for Jess full-time. They are entitled to £240 per week in benefits, including the SCP. Their income from work and benefits after they pay for their housing falls £10 short of the poverty line.

Calum is made redundant, and while he is looking for work the family fall much further into poverty. They are now £210 per week below the poverty line. Although their benefit entitlement, including support for housing, increases to £430 per week, it is nowhere near enough to replace their lost earnings from work.

Calum finds a new job, but it is in Glasgow, so the family decide to move there. Being back in work at the rLW lifts the family income back towards the poverty line, but it remains £30 below it. Rents are higher in Glasgow, pushing the family further from the poverty line. Yet they are still significantly better off than they were when neither Calum nor Mia was working.

The scenarios in this example illustrate how people’s incomes change in relation to the poverty line as a result of common life events: people lose jobs, people move house and babies are born. For too many, these everyday experiences come with too harsh a consequence.

There are, of course, many more aspects of people’s lives than income and housing costs which can make families feel strained or as if they are struggling to thrive. Indeed, there is much that is not included in this measure, such as energy, transport, childcare and food costs. And much work is rightly being done to reduce these costs.

While reducing these other costs might not impact poverty rates, they can make a significant difference to what families experience in the short term, giving them more money in their pockets. Though reducing these costs may have less impact on child poverty rates, it can have a knock-on positive impact on household income and, in turn, lift households out of relative poverty. Childcare is a good example of this.

Childcare as a poverty reduction tool

Childcare is an important policy area for poverty reduction for a number of reasons. However, we are focused on how childcare can reduce poverty and how it might impact low-income families’ ability to make ends meet. Figure 1 shows us how childcare costs and access to childcare can impact family incomes in relation to the poverty line.

To work out if a family falls above or below the poverty line, we use the family’s income (from work and/or benefits) after they have paid their housing costs (blue line).

If a family falls below the poverty line they can increase their blue and green lines by increasing their income or reducing their housing costs. Childcare can enable parents to move into more and better work and increase their income, moving the green and blue lines upwards.

We can increase a family’s remaining income, moving the pink line up, by reducing the cost of childcare – this will not show up in the poverty rate, but it will be felt by parents trying to make ends meet.

So we can measure success in childcare policy in 2 ways, as poverty reducing and as increasing the remaining income after a household has paid for childcare. Both of these benefit low-income households.

The experience of poverty

Vitally, there is also the experience of poverty that we hear about from the families in poverty with whom we work. The experience is not homogeneous, but it does have recurring traits such as stigma, fear, embarrassment and isolation that can all be dampened by good policy.

The 2 lenses of poverty, income and experience, must not be put in competition. Both need significant attention. But the idea that we have done enough for family incomes is palpably untrue. Similarly, to think that all that is needed is more money is also plainly untrue.

Instead, it is better to think about the relationship between the two being self-fulfilling. Then, the question becomes: how can policy prioritise to create the best outcomes for families? For example, we will show that a combination of work and social security is needed to lift families out of poverty. And, to give an individual the best possible chance at succeeding in the labour market, they should not go into work on the first day hungry, or worried if they can turn the heating on when they get home at night. This approach requires us to view social security as a preventative policy, giving people a platform from which to build.

Child poverty targets

The child poverty targets are a crucial framework for child poverty policy in Scotland. Even though progress has been slower than necessary, they have driven behaviour and have maintained a level of policy continuity since their creation. For example, it is doubtful the SCP would exist at current levels without these targets.

The targets explained:

The Child Poverty (Scotland) Act 2017 includes 4 targets for child poverty in Scotland in 2030 and interim targets for 2023. The targets require that, of all children living in Scotland:

- less than 18% are in relative poverty by 2023–24 and less than 10% by 2030–31

- less than 14% are in absolute poverty by 2023–24 and less than 5% by 2030–31

- less than 8% are in combined low income and material deprivation by 2023–24 and less than 5% by 2030–31

- less than 8% are in persistent poverty by 2023–24 and less than 5% by 2030–31.

The progress on the targets is widely available and details are published annually. The most recent statistics show that the Scottish Government has failed to meet the interim child poverty reduction targets. In Scotland, 1 in 4 children remain in poverty. To have met the interim target, a further 40,000 children would need to have been lifted out of poverty.2

To be clear, we are not setting the bar on the ambition; Parliament has already done that. We are setting the bar for the action needed to meet that ambition. There is no value at all in ambition without delivery.

3. How we built this toolkit

The analysis presented in this report uses the IPPR Tax-Benefit model to make changes to work and social security policies in Scotland. We have created a base scenario where we project current policy forward from now, with inflation assumed across elements such as earnings, benefits (including the SCP) and rents. This allows us to predict what we might expect the child poverty rate to be in 2030/31 if the Scottish Government were to take no further action. We have not included the mitigation of the two-child limit (unless otherwise stated) or changes at a UK level to Personal Independence Payment or disability elements of Universal Credit.

We can then make changes associated with different policies, like increasing the SCP, moving parents into work and increasing their pay or hours, but we keep everything else the same as the base scenario. This gives us an alternative child poverty rate that we can compare to the base scenario. Comparing each policy change to the base scenario lets us better understand the impact policies might have for families with children in Scotland.

We have also created 3 packages of policies that either meet, or get close to meeting, the child poverty targets. This is what those building manifestos for the next election will need to do if they want to meet these targets.

It is worth noting that modelling always has some level of variability. This is even more so in Scotland, where the data is more limited than is available at the UK level. Therefore, the values presented are indicative of how a policy may impact families in Scotland based on what we know at the moment. For example, they do not take into account how people’s behaviours may change in response to a policy (such as their incentives to take on more hours of work) or events such as those that contributed to the high levels of inflation seen in 2022.

4. Meeting the moment in the labour market

A job is often the thing that keeps people from poverty: if you are in work, you are far less likely to be in poverty. But work is no longer the protection from poverty it should be, and in-work poverty is rising. Of every 4 children in poverty, 3 live in a household where someone works (Scottish Government, 2025).

We know where in our economy in-work poverty is concentrated. Of all people in poverty where someone in their family works, nearly 3 in 4 (72%) have someone in their family working in one of just 5 industries (Birt et al., 2023).

We found that 1 in 10 workers in Scotland are trapped in persistent low pay, meaning that they have earned below the rLW for at least 4 of 5 years. Very few people in low pay are able to sustainably move out of low pay, with only 1 in 20 moving to pay above the rLW in the same 5-year period. A further 5% have moved in and out of low pay over the 5-year period.

We also know who is most likely to be in in-work poverty – of those in persistent low pay, 7 in 10 are women. And when you look across other characteristics like gender, ethnicity and disability, you start to see the broad systemic failure of the labour market. While this remains the case, we cannot shift the dial on poverty.

There are also too many people who could work but are currently locked out of the labour market by barriers that we as a society have built: the cost of childcare for parents that lock mostly women out of the labour market; the lack of social care, and its costs, to disabled people; poor and expensive public transport, particularly in rural areas; and, for some, outright discrimination.

If the current labour market is failing, what would a functioning one look like? Building this is a challenge that is made harder without direct powers over labour market policy. However, given the contents of the upcoming UK Employment Rights Bill, that will be less of an issue in the next Scottish Parliament.

The Bill looks like it will focus on many of the areas that the current Scottish Government have prioritised in their Fair Work agenda, including pay and security. While the Employment Rights Bill is a positive change, parts of the Scottish Government are so confident in the Bill that they are pulling back from their previous Fair Work commitments (Scottish Government, 2024). This is a mistake. Without action to improve labour market outcomes, it is inconceivable that we will see the required fall in child poverty. We have written extensively about the various policy options available to do this. Here we will highlight some key ones, but first, we will look at the impact that successful interventions could have, the scale that is needed and their potential fiscal benefit.

It is important to say here that parents are already working at very high levels, particularly in couple households (ONS, 2025). But there are still structural inequalities within the jobs market that prevent people from working as much, or earning as much, as they could or should.

Our modelling has focused on 3 general outcomes: moving into work, increasing hours and increasing pay. These modelled outcomes would all require careful policy support. They are intended to demonstrate the scale of change needed and the impact they could have.

What we modelled for work

- Increase parental work hours: In this scenario, we increase working hours for parents in poverty who are working part-time. We increase part-time hours to 30 hours per week for parents where the youngest child is aged 3–12 and to 35 hours a week if their youngest child is 13 or over. On average, this is an increase of 12 hours a week. This aligns with Universal Credit’s work requirement. We keep everything else about a parent’s job the same, so, for example, they get the same hourly pay and work in the same sector.

- Move parents that are not currently working into work and increase parental work hours: In this scenario, we increase part-time workers’ hours for working parents in poverty, like the scenario above, and move non-working parents into work if they are not carers (for children under 3 or adults) or in receipt of a disability benefit. For parents who move into work, the number of hours that they do is based on the age of their youngest child: 30 hours per week if the youngest child is aged 3–12 and 35 hours a week if their youngest child is 13 or over. Their hourly pay is the rLW and they move into a job in the private sector.

- Half disability employment gap: In line with the Scottish Government Disability Employment Gap targets, we modelled halving the gap in the employment rate for disabled and non-disabled adults. To model this, we moved around 120,000 disabled working-age adults into work. These new workers move into 16 hours of work paid at the rLW. The Scottish Government’s policy is, rightly, targeted at all disabled people – not just disabled people living in poverty or disabled people with children – so this is what we have modelled. As a result, and as we show, the impact on child poverty will be more modest than the scale of change required.

- Increase part-time (PT) pay for the lowest-paid workers: We know that low-paid part-time work is one of the drivers of poverty in Scotland. Low-paid part-time work is also often paid less than low-paid full-time work. Because of this, we wanted to look at the impact of increasing the hourly pay of low-income part-time workers to that of low-paid full-time workers.

- Increase pay to rLW for all workers: We raised workers currently paid below the rLW to the rLW, but kept them on the same hours as they already have.

- Increase pay above rLW to the single people rLW for all workers: To look at the impacts of a higher wage, we moved workers in Scotland to the single people rLW (£12.30 in 2023/24 compared to £12 for the rLW) but kept them on the same hours as they already have (Cominetti and Murphy, 2024). The single people rLW rate is the wage a single working-age adult would need to receive (when working full-time) to reach a decent standard of living. In comparison, the rLW is calculated as an average across single and couple working-age adults.

By far the most impactful scenario is where we increase parents' hours and move non-working parents into work at the rLW. This would reduce child poverty by 60,000 and result in a child poverty rate of 14%. It would require around 50,000 parents to move into work and around 20,000 to increase their working hours.

For context, the last Tackling Child Poverty Delivery Plan (Scottish Government, 2022a) aimed to provide support for 12,000 parents into work and to improve the quality of work for those already working. Funding for this policy was later cut and reallocated to increase public sector wages. The rationale given by the now First Minister was that the labour market was tight. While this may have been the case more broadly, it ignored the fact that different groups face different experiences of the labour market. The priority families, which the policy was originally aimed at, are a perfect example of this.

Disabled people

The findings from halving the disability employment gap show just how far disabled people are from a decent income – even when they are able to substantially increase their incomes through work. By halving the disability employment gap and moving disabled people into part-time work, we see a fall of 2% in the poverty rate for people who live in a working-age household where someone is disabled. We have shown the impact of achieving this goal by 2030/31; the Scottish Government target is to do this by 2038. This is a particularly pertinent issue for parties to face because of the coming cuts to sickness and disability benefits. The UK Government assert that support into work will make up for the cuts. This analysis shows how it rings hollow.

Other analysis has shown that the UK Government’s planned £1.8 billion extra investment in employment support over the next 4 years could help 45,000–95,000 more disabled people into work in the whole of the UK (Learning and Work Institute, 2025). However, this compares to an estimated 3.2 million people across the UK who will face benefit cuts. And pales in the face of the 120,000 disabled people in Scotland alone who would need to move into work to half the employability gap by 2038.

Hourly pay

We also wanted to look at the impact of hourly rates of pay, as they are a persistent part of the debate about poverty and child poverty. Both the Scottish and UK Governments can be accused of an oversimplified narrative around minimum wage policy.

Care needs to be taken in seeing the National Minimum Wage (NMW), and future increases to it, as a silver bullet. While matching the NMW to the rLW reduces child poverty a little, increasing parents’ hours and supporting people into work is significantly more impactful. As a result, it is not really legitimate for the Scottish Government to argue that devolving the powers to set the NMW would solve much of the problem, just as neither can the UK Government argue that increases to the NMW will significantly reduce poverty, never mind offset the ill-effects of already announced policy on disability benefits. It is not that it is not important, it is just not enough.

Scotland has some of the highest levels of rLW coverage in the UK, so this progress could be capitalised on. Hourly wages alone cannot solve child poverty, even if they are set at the rLW or slightly higher – this is primarily because the hours that people work or whether or not they work are more significant factors. The modelling here shows that moving all workers to the rLW would lift around 10,000 children out of poverty. While this is relatively modest, it is still equivalent in terms of the change in poverty rate to the ending of the two-child limit (and would clearly have the knock-on effect of lifting the wages of hundreds of thousands of people).

Helping parents to find work or increase hours

As we highlighted above, there are multiple structural barriers to why these parents are currently not in work or are working part-time. The next Scottish Government has several options to dismantle these to enable parents to get into work and move into better work. The correct combination at the right scale will have a positive impact on parents' labour market outcomes.

To ensure that the labour market can more fully support families out of poverty, parties will have to choose how to weight and sequence interventions. Prioritising those on the lowest incomes should be matched with a diagnosis of the biggest structural barriers. There are 2broad overlapping policy dimensions to get people into good jobs. Each of the following is a guide to what is needed, but significant thought will be needed to design and deliver them at the appropriate scale.

Access

The next step for early years childcare (ELC): A new early years childcare offer for 1- and 2-year-olds is needed. Low-income families should be prioritised for any expansion in the first instance. Upcoming work partly funded by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) will propose a capped income contribution model to ensure the next phase of ELC continues to see universal provision, but at free or very low cost for low-income families.

Redesign and enhance employment support offer: The ambitions outlined in Best Start Bright Futures, the most recent Tackling Child Poverty Delivery Plan (Scottish Government, 2022a), are inadequate in comparison to the scale of change needed. We have shown how many parents need to be reached, and there is much evidence on what works and what does not. One aspect is clear: services need to shift focus from trying to force individuals to fit the labour market to specific employers being more proactive in advocating and creating changes to how jobs are designed and supported.

It will be vital to understand how support for people in Scotland is delivered by the UK and Scottish Governments. Ensuring that they dovetail will be key to success.

Key industries: There is sometimes a bit of an overly simplistic assumption that in the future, everyone will work in a new emerging industry, but not everyone will become a heat-pump engineer or work in life sciences. While every effort should be made to ensure that access to these important industries is significantly widened to include those most likely to be in poverty, it is equally important to design a labour market for the economy we have, not just the one that we want. This means seriously evaluating the concentration of poverty in the 5 key priority industries, either to make every effort to make these jobs better (see below) or to support large numbers of people who are at risk of long-term low pay to higher-paid jobs and industries that match their competencies. For example, many of the skills needed to work in industries like hospitality and retail are highly transferable and desirable. They could be codified better, and government can work with industry to create pathways from these jobs to entirely new ones or to better jobs within those industries.

Quality

Operationalising Fair Work: For over a decade, the Fair Work agenda has outlined a vision for a Scottish economy where work is productive, fulfilling and fairly rewarded. It is time to move beyond discussions and reports to concrete action. The Government should establish dedicated teams, independent of government, to work directly with employers, helping them to implement Fair Work practices and to actively monitor and report on progress.

Broaden Fair Work First: Many of our scenarios include payment of the rLW. Fair Work First has shown a willingness to put conditionality on support for business. This can be extended to all types of government support that businesses in Scotland enjoy, for example, the Small Business Bonus Scheme.

Tackling workplace discrimination: Discrimination in the workplace, whether based on ethnicity, disability or gender, continues to be a significant barrier to employment for many. The Government should support the creation of an independent agency to address instances of workplace discrimination, providing a trusted route for employees to report issues and access support.

Prioritise progression: Progression should have equal status with participation when it comes to employment support strategy and services that are designed with people with lived experience of in-work poverty.

5. Meeting the moment with the social security system

It is helpful to remember the roots of our social security system:

... the aim of the Plan for Social Security is to make want under any circumstances unnecessary.

Sir William Beveridge, Social Insurance and Allied Services, 1942

Want is far too prevalent in Scotland, and while efforts to increase income from employment are the area that seems to have the most room for improvement, a strengthened social security system is needed.

But we need to move beyond a conversation about how inadequate the system is to making more proactive decisions about the objectives we want to achieve with our social security system. The child poverty reduction targets compel us to do so. To move beyond mitigating UK Government cuts to a system that provides the security its name demands. The forthcoming report on a Minimum Income Guarantee for Scotland provides a radical blueprint for that. Here, though, we concentrate on what is needed of the system to meet the targets.

Simply put, achieving the child poverty reduction targets will require additional spending on social security by the next Scottish Government. The logic for this is 3-fold. First, the well-documented general inadequacy of the social security system. Second, the targets demand very low levels of child poverty – some people will not be in work, either temporarily or permanently, and some people will not be able to work the hours necessary to achieve a decent income. Without improvements to the social security system, those unable to work will be left further behind, creating extreme hardship for that group. Last, as we show in the previous section, even with very large changes in labour market conditions, poverty rates would still be above the target levels – social security has to play its part.

It is perfectly reasonable for the current, and any future, Scottish Government to bemoan cuts to social security from the UK Government. Years of cuts, dressed up as ‘welfare reform’, have made the lives of people in Scotland and across the UK harder. On top of that, the forthcoming cuts to disability benefits will push many disabled people (a group already facing widespread hardship) into poverty. Ultimately, however, the Scottish Parliament did not set the targets subject to the actions of the UK Government – this might make the road harder, but the next Scottish Government still have to walk it.

Of course, part of that is the financial pressure that mitigating UK Government actions has on the Scottish Government budget. Between the mitigations of the social sector size criteria, often referred to as the ‘bedroom tax’, the benefit cap and the two-child limit, the Scottish Government is already committed to significant additional spending. Adding mitigation of the cuts to Personal Independence Payments is of another order of magnitude.

Yet, most importantly, additional social security spending is a choice to prevent people from falling into deep hardship and, more positively, to take significant steps towards meeting the child poverty reduction targets. It will require prioritising this kind of spending, or it will require additional revenue raising to pay for it; as we note, there is no free way to meet these targets.

Social security is a good preventative policy that provides a platform on which people can build their lives. It is also necessary to meet these targets, so we set out in this section a variety of options available to the next Scottish Government to build a route towards meeting the targets.

What we modelled

In this section, we used a variety of different approaches to show the potential of social security investments.

- No Scottish Child Payment (SCP): This shows what child poverty levels might be if the SCP did not exist (compared to its current level).

- Uplifting SCP to £40, £55, £75, £85 and £100 per child per week in 2026/27 and assuming yearly uprating to continue after, as promised by the Scottish Government.

- SCP priority family supplement: This is an additional SCP payment (at the given value of SCP for that year) for households with a baby, where someone is disabled and/or a single parent. If SCP is not increased above the rate of inflation, this would make the additional payment £30.30 per week per family in 2030/31.

- New disability payment for low-income families with children: Supplementary payment of lower rate of Adult Disability Payment for families where someone is disabled and in receipt of SCP.

- Improve SCP take-up to 100%: Increase take-up from 87% to 100% of all eligible families. This assumes that any family in receipt of a qualifying benefit is automatically given their SCP entitlement. However, it does not alter the take-up of qualifying benefits like Universal Credit.

- Mitigate the two-child limit: As the current Scottish Government has already committed to, this assumes that the Scottish Government would create a payment to compensate for the Universal Credit that is lost by the two-child limit and the benefit cap.

As we would expect, none of the interventions on their own would meet the child poverty reduction targets. Even a near quadrupling of SCP to £100 a week per child at an annual cost of £1.14 billion would see a child poverty rate 3 percentage points above the targets.

So, we know that it is a combination of social security and work that is needed, but we also know that for many families, the ability to increase their incomes from work is restricted by factors like caring responsibilities, lack of connectivity and employer attitudes and/or inflexibility. It is for this reason that we chose to look at supplemental payments for specific family types. For simplicity, we did this via the SCP for those in single-parent households, families with a baby and families with a disabled person. We also looked at the impact of a new separate payment that could be made to families in receipt of SCP where someone is disabled.

Targeting payments in these ways also targets the depth of poverty, as well as assisting other efforts to meet the targets. The supplements move more families closer to the poverty line than they do over it. This needs to be a key consideration of policy-makers when reducing poverty, as we have shown that while relative poverty has fallen, there remain 80,000 children living in very deep poverty. Children in poverty are now more likely to be in a family in very deep poverty than they were in the mid-90s. This is most likely due to current policies, like social security and employability, not making a sufficient impact in increasing their incomes to lift them over the poverty line. Meanwhile, high housing costs limit the impact of these policies, pulling household incomes down.

Reducing deep and very deep poverty not only tackles the most extreme forms of hardship but also increases the likelihood of other policy interventions succeeding. This is because the gap between incomes and the poverty line is currently so large. For example, the additional income needed to get out of poverty for the average person in very deep poverty translates to over £1,000 a month for a couple with 2 primary-aged children in very deep poverty. Bridging that gap, at the scale required, needs incomes from employment to work in concert with those from social security. For some families, social security will need to do all of the work (for example, for some carers and parents with babies).

A flat increase to SCP is clearly an available option that would undoubtedly reduce poverty. We do show that after a point, the impact on poverty diminishes, that is, the investment made compared to the impact on poverty starts to wane. As well as new and increased payments, for the targets to be reached, existing support must be maximised. We have shown that full take-up of SCP could lift up to 10,000 children out of poverty. Parties cannot ignore the need to create the environment and strategies to maximise take-up.

Finally, we have shown the impact of the mitigation of the two-child limit. This policy has already been committed to by the current Scottish Government, and we have shown it has the potential to lift 10,000 children out of poverty. This is a well-targeted approach and a response to the rapid, policy-driven growth in poverty for families with 3 or more children. The latest data shows that 41% of households with 3 or more children are in poverty; this compares to 28% a decade ago (Scottish Government, 2025).

6. Housing emergency

You cannot build a better future for yourself and your family without a warm, safe and secure home that meets your needs and that you can afford. Yet this remains out of reach for too many families in Scotland.

We will need to sweat every asset if we are to achieve the targets in the next Parliament so that parties cannot ignore the role good-quality, energy-efficient, secure and affordable housing plays in reducing child poverty. Keeping families out of expensive and inappropriate housing boosts their incomes after housing costs and enhances the impact that work and social security bring.

Yet today, Scotland has the highest recorded number of children stuck in temporary accommodation. This is heartbreaking and harmful. It is also a social policy failure at scale whose impact will reverberate for years without urgent action.

It will take significant and sustained public investment in new affordable and social supply, and support for housing costs, to address this. We would want to see bold demonstrations of political will to make good-quality housing a real, long-term priority by all parties to turn this around. The returns for families, local communities and the economy are significant, and such action will be supported by the public. Parties should focus their attention on prevention: this is a sound approach, and affordable housing is an excellent preventative policy.

Building the right kinds of houses in the right places will clearly improve the lives of families in Scotland. It will also play a part in reducing child poverty. An estimated 2 percentage points reduction could be achieved from relieving the burden of high housing costs on families, lifting 20,000 children out of poverty (Mitchell and Congreve, 2021).

That an increase in capital investment is needed to match the scale of the crisis is well understood, and the housing sector in Scotland has rightly called for the levels of investment required to reduce housing need to be clear, evidence-based, secure and long-term. It is the job of the Scottish Government, now and after the election, to answer this call and present a credible plan to tip the scales in favour of the urgent scaling up of social and affordable housing supply that is needed.

A credible target of building around 8,000 social and affordable rental homes a year would require well over £1 billion a year of public subsidy at current prices, assuming interest rates for borrowing remain steady or even come down a little. This cost will rise if there is to be an increase in the proportion of this housing that is for social rent. The Scottish Federation of Housing Associations, Shelter Scotland and Chartered Institute of Housing Scotland’s updated social and affordable housing supply analysis, due this summer, which will calculate the amount of need, as well as where and at what cost, will be instructive for those building manifestos.

It is well understood that the divergence in child poverty rates between Scotland and England and Wales relies on lower housing costs, including the higher proportion of social housing in Scotland. However, there should be no complacency about this. There must be a continuous drive to create a sustainable social housing market that matches the needs of our citizens.

Finally, politicians of all persuasions must unlock the considerable but unequal wealth locked in our housing and land markets and action reform of council tax. We may have lower bills in Scotland than elsewhere, but our modest and low-income families are still shouldering an unfair burden, and our local public services are starved of the resources they need to improve.

7. Combined modelling packages

The final part of this toolkit is where we have modelled packages of policies to show the extent of effort required to meet the targets: essentially, what an anti-poverty chapter of a manifesto could look like.

To achieve the large-scale change needed to meet the targets, multiple things will need to happen together, and quickly. It requires a significant change of pace from where we are now.

The changes to social security and the labour market that we have modelled separately become most impactful when they are layered on top of each other. However, they also become less straightforward to assess than the individual scenarios that we have modelled above.

For example, we know the cost of increasing the SCP in isolation and can attribute specific poverty reductions to that change, for example, an additional £190 million to increase the SCP to £40 in 2026/27. When, however, we include that uplift within a scenario that has also increased employment, we then see the demand for SCP fall because families’ incomes increase through work. At the same time, we know there is poverty reduction from both increased SCP and increased employment income; however, this is challenging to pick apart.

Costs versus returns

Obviously, the most important ‘return’ on the investment required to meet the targets is bettering the lives of 100,000 children in Scotland.

As we have noted elsewhere, however, the current state of public finances is such that it is crucial to consider how delivering a manifesto with such a radical change at its heart is paid for.

The scenarios modelled here will inevitably mean the Scottish Government having to spend additional funds on meeting the targets – there is no other credible way to do so. That means the next Scottish Government will have to find those funds, no doubt in competition with other demands and the additional strain caused by the UK Government’s cuts of disability benefits. As we have mentioned in the section on housing, council tax is long overdue significant reform and could be used to raise additional funds beyond those that are raised now. Non-domestic rates, usually called business rates, also provide a potential source of additional income. And, of course, the Scottish Government also has broad powers to raise additional funds via income tax.

Fundamentally, in making these choices, the next Scottish Government will have to decide whether they think it is acceptable to maintain around 1 in 4 children being in poverty. While a broader suite of tax powers would allow the SG to balance the types of income or wealth they raise revenue from, the political calculation is still broadly the same: can the parties defend, and deliver, the outcome (radically lower child poverty) against the income or wealth foregone by individuals?

As part of these considerations, in these modelled scenarios, we are able to show the expected positive impact on tax revenues as a result of the changes. Because of the complex funding mechanisms for the Scottish Government, it is not possible to extrapolate how much of these returns will accrue to the Scottish Government compared to how much will accrue to the UK Treasury. It is, however, instructive to see that poverty reduction efforts at scale can have significant positive impacts on tax returns due to increased labour market activity.

We are also able to show the direct costs of the social security measures we model, as well as any savings on social security spending. Due to the large increases in employment, and the accompanying rise in earnings from work, these all show a significant fall in Universal Credit expenditure. This is unsurprising as it reflects Universal Credit’s means-tested and demand-driven nature – it is a good outcome if people have achieved decent incomes through good jobs.

In some ways, the next Scottish Government could be a victim of its own success when it meets the child poverty reduction targets since, as we show here, much of the impact will come from labour market improvements. As such, not all of the knock-on benefits of such a radical change will accrue to them. Increased income taxes obviously would, but will be subject to the relative economic performance of the Scottish and UK economies, whereas increased tax taken from National Insurance contributions and savings via Universal Credit will accrue to the UK Government.

Related to that, we are not able to show the costs for the labour market changes. This is because there is a wide range of options available to parties on the labour market side. However, we can give an indication of the scale of costs associated with 2 of the most important policy areas, that is, how to deliver a world-class employment support service and a childcare offer that enables parents to move into better work at the hours they want.

Last year, JRF published a report that costed an example early years childcare offer (Evans and Cebula, 2024). It was based on a survey of parents, and taking an average of the funded hours that would suit them. The offer would be 20 hours a week for 1- and 2-year-olds and 35 hours a week for 3- and 4-year-olds. This would be a marked increase on the current offer and be available all year round, unlike the current term-time offer. The annual cost of this policy would be £3.2 billion, which is an increase of £2.2 billion from the current spend. We concluded that this cost of universal provision was too high given its relative impact on poverty levels and committed to looking at alternate models that would be targeted at low-income families and were more affordable given the current fiscal situation.

That work is due to be published later this summer and will propose an expansion of hours, but with an income-based contribution from parents. This would ensure the next phase of ELC continues to work toward universality of availability, but those who are able to will contribute to some of the expansion costs.

To move 50,000 parents into work will also take serious investment as well as a redesign of how the service is delivered. The cost of an employment support offer to match this ambition is difficult to cost accurately. To begin with, not all parents would require the same type of support. Indeed, many will not need any; rather, their labour market success will depend on the successful removal of barriers such as unaffordable childcare. Meanwhile, other parents may require more intensive support. Systems such as the Sure Start system in England provided this more rounded and tailored approach for parents and their children.

Also, while the Scottish Government has devolved powers in this area, there is still a significant role for the UK Government to play. Genuine collaboration between governments to support parents will reduce costs for both as well as improve experiences and outcomes for participants. The additional £1.8 billion that the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) has committed for employment support could, and arguably should, contribute to these outcomes too.

With all this considered, we would tentatively estimate an additional annual spend of £150 million for employment support in Scotland would be needed. This is based on the 2022 economic evaluation that produced the cost per person amount for successful participants in Fair Start Scotland, scaled up to meet the new demand that our modelling suggests is needed in today’s prices (Scottish Government, 2022b). This will of course vary based on the delivery model chosen, but we think it is a helpful marker for the scale of investment required.

What we modelled

We have looked at the separate scenarios with multiple social security and labour market changes. The packages below show the cost of the individual policies if implemented in isolation, not the cost within the given package. However, we do provide a total cost for targeted social security policies when combined.

Package 1 - Broad child poverty:

- move parents in poverty into work at 30 or 35 hours per week (depending on the age of their youngest child) at the rLW

- increase part-time parents in poverty to 30 or 35 hours per week (depending on the age of their youngest child) at a minimum hourly wage of the rLW

- increase SCP take-up to 100% (costs £60 million)

- increase SCP to £40 in 2026/27, making it £43.60 in 2030/31 (costs £190 million).

Child poverty rate achieved: 12%

Children lifted out of poverty: 70,000

Costs: This would cost an additional £250 million in targeted child benefits in Scotland (as well as other costs associated with increasing employment) – but would increase tax revenues by £410 million because of increased parental employment. Universal Credit expenditure could also fall by £500 million as demand for it falls due to higher incomes through work.

Package 2 - Priority group focus:

- move priority family parents (excluding disabled parents and parents of a baby) into work at rLW

- halve the disability employment gap

- supplement of £47 per week per family to families with a baby in receipt of SCP in 2026/27 (costs £60 million)3

- new disability payment for low-income families with children (in receipt of SCP) set at value of lower rate of Adult Disability Payment (£76 in 2026/27) (costs £360 million)

- supplement of additional SCP (of £40) for single parents in 2026/27 (costs £200 million).

Child poverty rate achieved: 13%

Children lifted out of poverty: 60,000

Costs: This would cost an additional £540 million in targeted child benefits in Scotland (as well as other costs associated with increasing employment), but would increase tax revenues by £360 million because of increased employment (both parents and disabled people). Universal Credit expenditure could also fall by £720 million as demand for it falls due to higher incomes through work. This is larger than in other scenarios, as the cohort of disabled people helped into work is not restricted to parents.

Package 3 - Combined:

- move parents in poverty into work at 30 or 35 hours per week (depending on the age of their youngest child) at the rLW

- increase part-time parents in poverty at 30 or 35 hours per week (depending on the age of their youngest child) at a minimum hourly wage of the rLW

- increase SCP take-up to 100% (costs £60 million)

- increase SCP to £40 in 2026/27, making it £43.60 in 2030/31 (costs £190 million)

- supplement of £47 per week to families with a baby in receipt of SCP in 2026/27 (costs £60 million)

- new disability payment for low-income families with children (in receipt of SCP) set at value of lower rate of Adult Disability Payment (£76 in 2026/27) (costs £360 million)

- supplement of additional SCP (of £40) for single parents in 2026/27 (costs £200 million).

Child poverty rate achieved: 10%

Children lifted out of poverty: 90,000

Costs: This would cost an additional £920 million in targeted child benefits in Scotland (as well as other costs associated with increasing employment); it would also increase tax revenues by £410 million because of increased parental employment. Universal Credit expenditure could also fall by £500 million as demand for it falls due to higher incomes through work.

The 3 packages presented here show the range of options available for policy-makers. They show that if parties choose to act, there is much that can be achieved. They also show that the parties cannot have their heads in the sand; if they want to meet these targets, they need to take action at scale. And even with the extent of changes we model here, these options do not necessarily meet the targets – although modelling a precise outcome is both very difficult and would not undermine the massive progress that these modelled changes would imply.

These options also show there are decisions to be made about how to meet the targets, whether that be by targeting activity at the groups most likely to be in poverty, or those more likely to be in deeper poverty.

It would be a legitimate policy objective to focus on those with the most difficult circumstances in the next parliament. That is, to genuinely make the priority families a priority. For example, that the child poverty rate for children in minority ethnic families is double that of all children is a stain on Scotland’s social justice efforts. Package 2 shows that through concerted efforts we can almost halve this child poverty rate and make large impacts on the other priority families (as seen in Table 1).

| Priority group | Poverty rate 2020–23 (%) | Poverty rate in 2030/31 (Base) (%) | Poverty rate after targeted scenario (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baby | 37 | 32 | 23 |

| Single | 31 | 32 | 13 |

| Large family | 38 | 25 | 20 |

| Minority ethnic | 53 | 39 | 26 |

| Household where someone is disabled | 27 | 22 | 13 |

This is an illustration of what this toolkit is intended for. Parties need to look within and decide how they approach the task of reducing the harms they are most concerned about. The poverty rates in this scenario are still clearly too high, but given where they are starting from, double-digit percentage point reductions for all these family types would be a huge achievement.

8. Conclusion

The final package demonstrates what a full-throttle approach to tackling child poverty would look like. It would see every fibre of every muscle strained in service of ensuring children in Scotland had the best chance of growing up and fulfilling their potential. It would require the next Scottish Parliament to come together as they did to unanimously pass the Child Poverty Act. This time, they would need to come together in delivery, not just in spirit.

And that will be the ultimate test of the next Scottish Government. Can it deliver in ways it has never done before? Can it deliver in the face of global tumult, the rise of extremism and a public’s trust in politics rapidly fraying?

The answer to this is it must, or we will see more children have their futures stolen. And the value placed in devolution and democracy will be eroded further.

There will rightly be some concern that change at this scale and pace may not be possible. It would be naïve to deny that the changes to the labour market demanded by these scenarios will be difficult to deliver in this time. To argue that they are impossible, however, is to deny the agency of everyone with the power to make a difference to do so.

In short, it is acceptable to fail, but it is unacceptable not to try.

The first marker that will be laid down in this bid for a lasting change in our society will be the parties’ manifestos. We hope that this toolkit provides some guidance on the options available and their potential impacts that will enable them to meet the moment.

Notes

- For further details on this equivalisation process, see the Scottish Government’s (2025) Poverty and Income Inequality report.

- 40,000 was calculated using the single-year averages published in Poverty and Income Inequality statistics (Scottish Government, 2025).

- We modelled an additional SCP of £47 for families with a baby under the age of one to mimic increasing Statutory Maternity Pay (SMP) to one year for low-income families. In this scenario, we took the amount of SMP that would be accrued over the remaining 13 weeks of the year and paid this weekly across the year. This is just illustrative, and for some families in the data, this weekly payment will be paid over and above SMP, while for others, they will not be receiving SMP.

References

Birt, C. Cebula, C. Evans, J. Hay. D. McKenzie, A. (2023) Poverty in Scotland 2023

Cebula, C. (2025) Children being left behind: Deep poverty among families in Scotland

Cominetti, N. Murphy, L. (2023) Calculating the Real Living Wage for London and the rest of the UK: 2023

Congreve, E. Randolph, H. (2022) The rationale for employability support

Evans, J. Cebula, C. (2024) Poverty proofing the future of early years childcare

Gibb, K. Young, G. Earley, A. (2024) Sustainable housing policy in Scotland: Re-booting the affordable housing supply programme

Learning and Work Institute (2025) Estimating the impacts of extra employment support for disabled people

Milne, B. Matejic, P. Stirling, A. (2025) Economic and employment growth alone will not be enough to reduce poverty levels

Mitchell, M. Congreve, E. (2021) Mission (not) impossible: How ambitious are the Scottish Government’s child poverty targets?

Office of National Statistics (ONS) (2025) Employment rate of parents living with dependent children by family type and age of the youngest child in the UK

Scottish Government (2022a) Best Start, bright futures: Tackling child poverty delivery plan 2022 to 2026

Scottish Government (2022b) Fair Start Scotland: Economic evaluation

Scottish Government (2024) Retail Industry Leadership Group meeting minutes: November 2024

Scottish Government (2025) Poverty and Income Inequality in Scotland 2021–24

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Hannah Randolph at the Fraser of Allender Institute for quality assuring this analysis, and Deborah Hay and Becky Milne at JRF for policy and analytical support throughout the project.

How to cite this report

If you are using this document in your own writing, our preferred citation is:

Birt, C., Cebula, C. and Evans, J. (2025) Unlocking the potential of young people furthest from the labour market. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

This report is part of the child poverty topic.

Find out more about our work in this area.