Energy affordability: how to reduce bills for majority of households

The Government needs a new approach to tackling energy affordability. A rising block tariff could be the answer.

Executive summary

Energy is unaffordable for too many households in the UK. Bills remain £600 above their pre-energy crisis average, and energy debt is at an all-time high (Marshall, 2025). In the coming years, bills are set to rise even further as additional policy costs are passed on to consumers.

This affordability crisis is eroding living standards. The pressure is most acute for those on the lowest incomes, with fuel poverty rates remaining stubbornly high. But high energy costs are also placing pressure on household finances much further up the income distribution, with 15% of households on middle incomes reporting that they are struggling to heat their homes.

It is therefore unsurprising that the cost of energy is at the top of the public’s mind when they think about the cost of living crisis. This is having a wider political impact. The high cost of energy, and the perceived failure to bring these costs under control, is eroding trust in the Government, fuelling a sense that mainstream politics is not working and is contributing to a fraying public consensus around net zero.

Clearly, there is a strong moral, economic, and political imperative for the Government to take action to bring the cost of energy bills down.

The affordability crisis demands a bold response

This imperative to act has led to the development of a number of proposals designed to address energy costs. This paper assesses these options against a set of principles that we think should guide any policy intervention to address high energy bills:

- maximising progressivity

- redistributive efficiency

- delivering support to the majority of households

- supporting the transition to net zero

- feasible to deliver under existing conditions.

We assess 5 approaches to reducing energy bills: delivering support through the social security system through an increase to the Warm Home Discount, introducing an income-based social tariff, removing VAT from energy bills and introducing a rising block tariff (RBT).

Each of these proposals has strengths, but when assessing them against our principles, we find most are beset by 1 of 2 issues. Either they are targeted very narrowly on the lowest-income households (the Warm Home Discount) and therefore do not reach all those who are struggling with their bills. Or they rely on targeted support based on household incomes, which requires data that is not currently available, undermining their feasibility.

This is perhaps why removing VAT has become a much-discussed option pre-budget. While removing VAT from bills would overcome feasibility issues and deliver support broadly, it also has limitations. It is regressive, with the largest cash savings going to higher-income, higher-consuming households. This is both inefficient in redistributive terms and also potentially in tension with action to reduce carbon emissions. It is also capped as an amount of support, and once removed it leaves little room for further adjustment.

In contrast, we found that an RBT produces progressive outcomes while delivering support to the majority of households with relatively low barriers to implementation.

RBT means targeted, progressive support for the majority

An RBT works by splitting bills into a series of ‘blocks’, each with a different unit price. Typically, each block corresponds to a certain amount of energy consumption. For example, households might be charged a lower unit rate for the first 40 kWh of energy they consume and then a higher unit rate for the energy they consume above that point.

Commonly, the RBT is designed as a means of both distributing and funding a discounted block of energy. However, as the debate around the standing charge and energy policy levies has shown, raising money via energy bills is far from ideal. While the RBT provides a mechanism for doing so that is more progressive than current approaches, this has nonetheless led to critiques of the policy. These typically focus on the risk of creating a small number of low-income, high-energy consumption households that lose out.

We discuss how this can be overcome in two ways. First, by introducing carve-outs for those on means-tested and disability benefits and offering higher allowances for households with children, which allow consumption to more accurately track income. Second, by funding the lower unit cost – in part or in whole – through government subsidy, thus eliminating or reducing the creation of losing households.

In practice, this means the Government could offer a universal cut to energy bills, delivered as an initial block of subsidised energy.

In comparison to removing VAT, implementing an RBT would maximise progressivity. If the same level of funding needed to remove VAT from energy bills was used to fund an RBT instead, it would lead to more progressive outcomes, with the bottom decile saving £128 (compared to £104 under the VAT cut) and the top decile saving £89 (compared to £128 under the VAT cut).

RBT can reduce bills now and in the future

A further benefit of the RBT is that it provides a flexible tool that allows governments to vary the depth of support available and the level of cross-subsidy within the energy billing system. For example, were an RBT to be set such that it delivered a discounted block set in line with essential energy needs, and which was funded by public subsidy, it could reduce energy bills for the median household by £150 a year at a cost of £5 billion.

Government should be bold in funding energy bill support

Delivering energy support in this way will require government to raise a sufficient amount of money to redistribute through the billing system. But, given the moral, economic and political imperative to act, we consider this a necessary step for government to take, even in fiscally constrained circumstances. We propose 3 ways through which government can raise the money needed to fund an RBT:

- Through general taxation. There is a live debate about the limits of funding social and environmental programmes through levies on bills and the potential for these levies to instead be paid for via general government spending. The same argument stands for funding energy affordability support; doing so via general taxation is the most progressive means of raising the money necessary.

- Through a levy on energy network profits. UK gas and electricity network operators earned approximately £4 billion in excess profits between 2021–2024, significantly exceeding Ofgem’s allowed returns through regulatory loopholes, particularly by benefiting from lower-than-expected debt interest rates. There is a case for recapturing some of these profits from a levy and directing this towards reducing energy bills. We estimate that it would be possible to raise around £1 billion a year through this approach.

- Through the billing system. An RBT allows for both distributing savings to lower consuming households while raising the money to fund this through higher consuming households. A combination of funding an RBT with a subsidy plus a small premium on higher levels of consumption would both limit the cost to the Government and improve the progressivity of the model by recapturing some of the subsidy given to higher-income, higher-consumption households. This would also lead to greater savings for lower-income households. Alternatively, an RBT could be a method of progressively removing or reallocating levies from electricity bills.

The UK’s current energy system fails to guarantee that all households can afford the essential energy needed for a decent quality of life. With millions struggling, the Government needs a new policy lever that provides both depth and breadth of support. We hope that this paper will support renewed debate on how to deliver the type of energy system we need.

1. Introduction

The Government faces 2 key challenges in relation to the energy system: affordability and the transition to net zero. Over the next 10 years, investment in renewable generation will make energy more affordable, but with bills £600 above the pre-crisis average, households across the UK cannot afford to wait (Marshall, 2025). At the same time, attitudes towards climate change are shifting. Recent polling for ‘The Times’ found that 25% of adults in Great Britain feel the risks of climate change have been exaggerated, up from 16% in 2019 (Wright, Vaughan and Bradley, 2025). Climate sceptics have long argued that net zero is responsible for the UK’s high energy bills. The longer that energy affordability is left unaddressed, the more opportunity there is for these arguments to shape public debate. To build public consent for the transition to net zero, the Government and the energy industry need to take energy affordability seriously.

Various solutions to this dual challenge have been posed, from rebalancing policy levies or removing VAT to introducing a social tariff. Each of these solutions is underpinned by 2 key questions: who pays? And who benefits? At the moment, energy affordability policy — in the form of the Warm Home Discount — suggests that all households should pay equally towards support that is given to households in receipt of means-tested benefits. However, recent polling from More in Common suggests that public consensus around this approach is at risk of breaking down. The polling found that households that were struggling to pay their bills but were ineligible for government support reacted negatively to energy affordability initiatives that only targeted the most vulnerable (More in Common, 2025). As a greater number of households struggle to afford their energy bills, the Government lacks the policy mechanisms it needs to take action.

In this paper, we explore the development of a majoritarian support system and compare it to more targeted approaches to support. We assess support through the social security system, an income-based social tariff, a cut to VAT on energy bills and an RBT against the following policy principles: progressivity, efficiency, majoritarian impact, alignment with net zero and feasibility. The paper then focuses specifically on the RBT based on its potential to deliver support to the majority of households in a progressive way. We assess the various trade-offs associated with an RBT and begin to chart a path to overcoming them – looking in particular at alternative methods for paying for the support.

In the current political and fiscal context, it can be tempting to focus on pragmatic tweaks to the existing system, but the scale of the challenge the Government faces demands an ambitious response. We need an energy system where all households have access to the essential energy they need to live their lives. This will require a fundamental change in how we think about energy — that is, moving from a system in which energy is used according to ability to pay, to one in which everyone’s essential needs are met. Getting there will not be easy, but we hope that this paper — and the new modelling included within it – will help to advance the policy debate.

2. Impact of high energy bills

The high cost of energy in the UK is being driven by a variety of factors, including the marginal pricing system, the UK’s reliance on the volatile international gas market, the accrual of policy costs on energy bills and the way that private ownership extracts dividends from the system. The impact of these structural problems is exacerbated by a regressive billing system that means that lower-income households spend a higher percentage of their bills paying for fixed costs than higher-income households.

The combination of these factors has produced an affordability crisis. In the latest round of our cost-of-living survey, 23% of low-income households said they had not been able to keep their home warm (Milne et al., 2025). Data from Ofgem shows that households in arrears now owe on average £1,600 to their energy supplier. This equates to £4.43 billion worth of debt across the energy market (Ofgem, 2025). People have been forced to make difficult choices to deal with energy unaffordability. Our latest cost-of-living polling found that 24% of low-income households in energy debt reported visiting a food bank in the last 6 months and 67% reported going hungry in the last 30 days (Milne et al., 2025).

These trade-offs are reflected in the experiences shared in our grassroots poverty action group. In January of this year, one member said:

I have a medical condition, so I need to keep the heating on at a higher level. It’s not a luxury, it’s so I can make life liveable. I haven’t turned my hot water on for 2 years so that I can afford to heat my house.

Age 50–59, North West England

Over the last 12 months, energy bills have been the biggest driver of the cost of living crisis for low-income households while also contributing to ongoing inflation in the rest of the economy (House of Commons Library, 2025).

However, households on the lowest incomes are not alone in suffering the effects of the cost- of living crisis. Analysis carried out by the Nuffield Politics Research Centre found that ‘around 18.5 million adults in Great Britain feel economically insecure, greater than the proportion in poverty and equivalent to around 35% of the eligible British voting population’ (Nuffield Politics Research Centre, 2025).

Few households have escaped the impact of high energy prices. Data from the 2023/24 Family Resources Survey shows that the struggle to maintain a warm home extends up the income deciles, with over 15% of families in the fifth income decile experiencing heat deprivation:

Data from More in Common shows that anxiety about energy bills also affects higher-income households. Among households with an income between £50,000 and £59,000, 35% report that they are very worried about energy bills this winter, and a further 36% say they are somewhat worried. Concern about energy bills only begins to reduce for households with incomes above £100,000 (More in Common, 2025). More than a quarter of households (28%) stated that they had experienced increased stress and anxiety because of high energy bills. Focus group participants said that living in cold homes made them feel like they were not able to move forward in life. At the same time, participants expressed little faith that the Government was taking the necessary action to make energy bills more affordable.

All households should be able to meet their essential energy needs and afford the energy necessary for a decent quality of life, through the transition to net zero and beyond. However, the Government currently lacks the policy architecture needed to distribute the widespread support that is needed to bridge the gap between where we are now and the low-cost, low-carbon energy system of the future.

3. Principles for designing energy affordability support

We believe that energy affordability support should be shaped by 5 key principles:

- Progressivity. The billing system must evolve from the current regressive pricing structure to a system that maximises progressivity. Any redistribution of costs should minimise the losses and maximise the gains for low-income households.

- Redistributive efficiency. Any affordability intervention should be tested on how efficiently it delivers progressive outcomes. This means assessing both sensitivity — the extent to which the intervention reaches households that need support, and specificity — the extent to which the intervention supports households that do not need support.

- Support the majority. In addition to supporting those on the lowest incomes, energy affordability support must also be designed to bring down bills for the majority of households. This will play a crucial role in building public consent for the transition to net zero and tackling broader living standards pressure.

- Policy infrastructure and the transition to net zero. The energy system is set to change significantly over the course of the next 5 years — with increasing investment in renewable generation, upgrades to the energy network, widespread roll-out of demand-side flexibility and adoption of low-carbon tech like heat pumps and electric vehicles (EVs). Any change to the energy billing system should work to accelerate the transition while protecting households through a period of change.

- Feasibility. All policy interventions should be assessed for their feasibility under current conditions. That means that the infrastructure needed to enact the policy change should already exist or could feasibly exist.

4. Policy solutions

While a variety of approaches to energy affordability exist, this paper will focus specifically on options that amount to direct support for bills. Existing policy proposals related to direct bill support generally fall into 1 of 3 camps. The first focuses on offering bill support through the benefits system, the second on creating an income-based means-testing system within the energy market and the third on using consumption data to implement an RBT. There are several ways of designing each of these interventions. Broadly, support through the benefits system would entail offering a rebate to households in receipt of means-tested benefits, an income-based means-testing system would deliver support to households below a particular income threshold (either via a flat payment or a unit-rate discount) and an RBT would offer a discount for an initial block of energy consumed, followed by a higher unit price for consumption above that threshold. We will also analyse a proposal to remove VAT from energy bills (currently charged at 5%), which the Government is rumoured to be considering.

Modelling

We have analysed the impact of each of these policy solutions using a model generated by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) and the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR). The model uses data from the living costs and food survey from 2018–2022 alongside the IPPR tax-benefit microsimulation model. Energy consumption data is derived from expenditure estimates and average price information. Consumption in kWh per week is estimated by dividing each household’s gas and electricity expenditure for each payment method by the average price for that payment method in their region of residence. As a result, the standing charge is incorporated into the unit rate in the model. Further details on the modelling can be found in a separate technical appendix.

Assessing the options

The table below provides an assessment of each of the policy options in relation to the principles outlined above.

| Policy approach | Progressivity | Efficiency | Majoritarian | Net zero | Feasibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social security system | Good | Good | Poor | Poor | Good |

| Income-based social tariff | Good | Average | Average | Poor | Poor |

| Removing VAT | Good | Poor | Good | Poor | Good |

| Rising block tariff | Good | Average | Good | Average | Average |

Each approach has its strengths and limitations.

Social security system

Delivering support through the benefits system is progressive and would be easy to administer using the existing Warm Home Discount eligibility criteria. However, analysis of the Family Resources Survey 2023/24 found that around 40% of households that could not keep their homes warm were not in receipt of means-tested benefits. This means a significant proportion of households that are struggling would miss out on support. More broadly, delivering support through the benefits system has no positive impact on the transition to net zero, either in terms of incentivising certain forms of consumption or creating future-proof policy mechanisms.

Income-based social tariff

An income-based social tariff is also a progressive way of distributing support and has the significant benefit of reaching households beyond the benefits system. How efficiently the policy is targeted would depend on the income threshold selected and the extent to which the eligibility criteria were able to reflect variations in costs of living and household composition. The same question about income threshold applies to the majoritarian principle, though it is worth noting that an income-based social tariff would, in principle, be capable of delivering support to a majority of households. Previous recommendations for income-based social tariffs have set the income threshold at £25,000 per household, which is unlikely to meet the majoritarian criteria (SMF, Citizens Advice and Public First, 2024). Instead, we modelled the effect of distributing £3 billion of funding via an income-based social tariff (equivalent to £216 per household) to all households with incomes of £33,000 and below (after deductions) and saw a strongly progressive trend with the biggest wins for the lowest income households and winners at the median (Figure 2).

However, like the benefits system approach, an income-based social tariff would not have a meaningful impact on the transition to net zero, though the means-testing system could be used to target other interventions in the energy system (for example, to determine eligibility for energy efficiency measures).

The greatest challenge associated with an income-based social tariff is feasibility. To operationalise the means-testing system, Ofgem and the Government would need to establish a system of data sharing across HM Treasury, Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and energy suppliers. Despite significant efforts from the third sector to encourage the Government to facilitate this, there are few signs that progress on data sharing will be made before the end of this parliament. Beyond the data sharing element, it is also worth noting that population-wide household-level income data is not currently collected by government. Instead, individual PAYE data is collected, but relying on this data set runs the risk of excluding 4.38 million self-employed people — who are nearly twice as likely to be in poverty as employed people — and also presents non-trivial challenges in estimating the incomes of household units as opposed to taxable individuals (JRF, 2025). The system would also need to be able to navigate changes to income in the middle of the tax year as a result of changed employment circumstances and account for incomes from other sources like interest on savings and investments, and private pensions.

Removing VAT

Speculation that the Government is planning to remove VAT from energy bills reflects an appetite for an intervention that would support the majority of households. Removing VAT would cut bills for all dual-fuel households by £86 a year (Shepheard, 2025). It is also a relatively simple change to make and is unlikely to require wider changes to the energy billing system. However, cutting VAT across all energy bills is less progressive than delivering support through the benefits system or introducing an income-based social tariff.

Figure 3 shows that removing VAT would benefit households in decile 10 slightly more than delivering support either through the benefits system or via an income-based social tariff. It would also have the lowest impact on household incomes in deciles 1 and 2. This poor targeting is particularly worrying because low-income households spend on average 16% of their income on energy compared to 2% for the wealthiest households (Shepheard, 2025). Removing VAT also does little to support the transition to net zero, and by reducing the marginal price of consumption, particularly on gas, it could in fact undermine decarbonisation efforts. Finally, while a cut to VAT could be implemented quickly, it does not provide a long-term policy lever. Once it has been removed, the Government is left without any way of providing further support to middle-income households or reacting to wider changes in the energy market.

Rising block tariff

An RBT splits bills into a series of ‘blocks’, each with a different unit price. Typically, each block corresponds to a certain amount of energy consumption. For example, households could be charged a lower unit rate for the first 40 kWh of energy they consume and then a higher unit rate for the energy they consume above that point. Typically, it is assumed that the higher rate of energy will provide a cross-subsidy to pay for the lower rate of energy. However, as we will explore, there are many ways an RBT can be designed to vary the amount of consumption included in the cheapest block, alter the size of the discount and the premium, protect certain households from the higher rate, or even introduce a third pricing block.

In our model, we have begun by separating the 2 key components within an RBT: a discounted block of energy and a premium block of energy. This allows us to test the strength of the RBT as a mechanism for distributing support and then separately to consider the question of how that support is paid for.

To understand the extent to which an RBT is able to distribute support, we have modelled its impact on household bills using the following parameters:

| Means-tested and disability benefit protection | Universal allowance kWh per week | Allowance per child kWh per week | Unit rate discount on lower block (%) | Unit rate premium on higher block (%) | Bill saving for median household | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electricity | Y | 40 | 10 | –15 | 0 | £150 |

| Gas | Y | 104 | 25 | –5 | 0 |

For each iteration of the RBT model, we have kept the essential energy thresholds constant. The consumption thresholds approximate an ‘essential’ level of consumption as calculated by the New Economics Foundation in their previous work on the National Energy Guarantee (Chapman and Kumar, 2023). The electricity threshold represents 77% of typical annual electricity usage and the gas threshold represents nearly 50% of annual gas usage (Ofgem, 2025). We have also included several protections to ensure that households in receipt of means-tested or disability benefits only ever pay the discounted unit rate, and that all households receive an additional consumption allowance per child.

The 0% premium on the higher unit rate block indicates that the unit rate is the same as the current market rate, that is, there is no additional premium being placed on consumption above the ‘essential’ allowance.

Results

The results reflect the progressive potential of an RBT, both in relation to consumption (Figure 4) and income (Figure 5).

As Figures 4 and 5 show, households in the bottom income deciles experience the most significant reduction in bills, but all households would see their bills come down. By providing a universal block of discounted energy, an RBT can extend support beyond the benefits system while ensuring that households in most need receive the greatest level of support.

Depth of support

Based on the modelling, the cost of delivering a £150 bill saving to the median household is just under £5 billion, falling to just over £4 billion if the carve-outs for households in receipt of means-tested and disability benefits are removed. The carve-outs are necessary in an RBT system that introduces a significant premium on the second block, but in an RBT that is entirely funded by external subsidy, the carve-outs simply deepen the level of support provided. All the models below include these additional protections.

While it would cost £5 billion to deliver a median bill saving of £150, it is possible for this level of support to be scaled up or down depending on the Government’s priorities and level of need.

As more money is injected into the RBT system, the size of average savings for the median household increases while the progressive distribution of those savings remains the same.

The modelling shows that, for example, £6 billion a year of funding could be used to reduce energy bills by £180 per annum. This cost may fall over time as investment in renewables begins to reduce wholesale prices. However, funding of this scale is not necessary to begin making a dent in household energy bills. As Figure 7 demonstrates, £2 billion of funding would reduce bills for the median household by around £60 a year.

Comparing interventions

This paper has reviewed a number of approaches the Government could take to reducing energy bills – from distributing money to households via the social security system or creating an income-based social tariff to cutting VAT or introducing an RBT. Figures 8, 9 and 10 compare each of these approaches across several metrics in a scenario in which £3 billion is spent on support. The charts include options to deliver support through the social security system and via an income-based social tariff. However, we believe that both policy options have significant limitations. Delivering support via the social security system does not meet our test for a majoritarian intervention, while the income-based social tariff has substantial feasibility challenges. Therefore, while they are included for reference, our analysis will focus on the RBT and the cut to VAT.

Figure 8 shows that removing VAT or introducing a fully funded RBT benefits all households. In comparison, introducing an income-based social tariff or delivering support through the social security system targets fewer households.

While a VAT cut and a fully funded RBT both provide support to all households, Figure 9 shows that an RBT maximises progressivity.

This is further underlined in Figure 10, which shows that a cut to VAT would deliver greater bill reductions to households in decile 10 than those in decile 1. In comparison, an RBT would deliver greater savings to lower-income households than those at the top of the income distribution.

When combined with the limitations of delivering support solely through the social security system and the feasibility challenges associated with developing an income-based social tariff, these figures reveal the strength of an RBT as a mechanism for delivering energy affordability support.

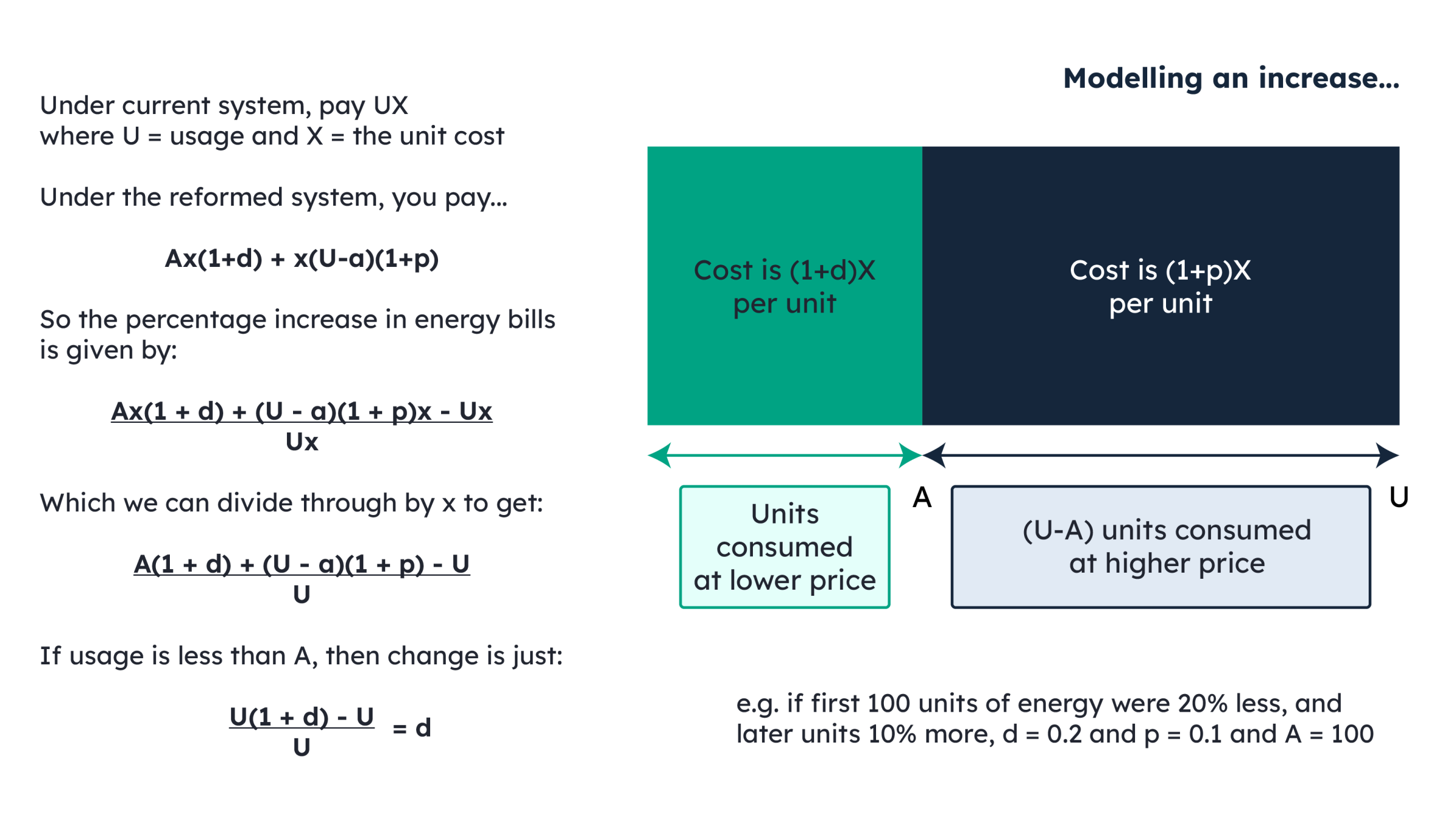

5. How to pay

The key question, therefore, and one that is a consideration for all the policy interventions we assessed, is how to pay for this support – whether from support through the benefits system to a cut to VAT. Under the current system, energy affordability support is funded through the billing system via the standing charge. This is regressive because low-income/low-consumption households spend a higher proportion of their bills on the standing charge than high-income/high-consumption households do. In contrast, if policies are funded through additional charges on the unit rate, they risk penalising those low-income households that have high levels of energy consumption. It seems obvious, therefore, that support should be funded from outside of the billing system. However, in the current context, there are political and fiscal constraints on funding and a desire to look for fiscally neutral approaches.

We consider both options, assess the trade-offs and propose a hybrid approach to funding that could move the debate forward.

The billing system

While the versions of the RBT modelled above do not levy an additional premium on consumption above the essential threshold, it is possible to do so. By increasing the premium on units consumed above the essential threshold, it is possible to create a fiscally neutral system of cross-subsidy that could deliver the equivalent bill saving as £3 billion worth of support. This cross-subsidy approach is how an RBT is typically conceived.

We modelled this approach using the following parameters:

| Means-tested and disability benefit protection | Universal allowance kWh per week | Allowance per child kWh per week | Unit rate discount on lower block (%) | Unit rate premium on higher block (%) | Bill saving for median household | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electricity | Y | 40 | 10 | –14 | 40 | £90 |

| Gas | Y | 104 | 25 | –8 | 14 |

Figure 11 shows the distribution of winning and losing households, revealing both the progressive nature of this funding mechanism and the extent to which it continues to deliver bill reductions for the majority of households, including those on middle incomes.

When compared to the other policy options we have tested, apart from distributing support through the social security system, a fiscally neutral RBT is by far the most progressive approach (Figure 12).

This is made even more clear when looking at average bill changes (Figure 13).

However, only looking at average bill change obscures some of the important impacts a fiscally neutral RBT has within income deciles.

Figure 14 provides a more detailed picture of the scale of wins and losses. For 87% of households in decile 1 that will ‘win’ because of the RBT, energy bills will reduce by £188 on average. This figure is even greater for winning households in income decile 2, who will see bills fall by £210 on average.

However, this data also reveals some of the significant trade-offs associated with funding energy affordability support using an RBT. In the previous iteration of the model, where the RBT is used solely as a method for distributing support, all households see their bills decrease. However, when an above-market-rate premium is introduced to pay for that support, some households will experience bill increases. Between 30% and 40% of households in deciles 5–7 are set to lose by around £200, while 14% of households in decile 1 are losing by £205 on average. At the same time, some low-consumption high-income households are winning, 38% of households in decile 10 are winning by £110 on average.

These inefficiencies are driven by complexities in the relationship between income and energy consumption. Figure 15 shows that higher-income households consume greater amounts of energy than lower-income households.

More specifically, it shows that inequality in energy bills primarily arises between households in the top 3 income deciles and households in the bottom 7. However, there are also significant variations in consumption within income deciles.

Figure 16 shows the extent to which this variation is driven by household size, but other significant factors include disability, age and energy efficiency. These variations affect the efficiency with which the RBT can distribute support to households that need it most. We have incorporated these intra-decile differences into our policy design to better protect low-income high-consuming households. This includes stipulating that households in receipt of means-tested or disability benefits will only ever pay the discounted unit rate for all their energy and providing an additional consumption allowance per child to better capture household size. However, relying on the benefits system to improve targeting is an imperfect solution.

When we analysed the characteristics of households in decile 1 that were losing out because of the RBT, we found that most were not in receipt of means-tested benefits.

Data from the family resources survey shows that 12% of families that cannot afford to heat their homes could be eligible for benefits but do not receive them. This means that encouraging benefits uptake would help to reduce the size of the low-income losing group. Equally, one could develop an alternative method of joining the protected group that does not rely on the benefits system but instead takes the form of an income-based opt-in scheme or a social prescribing route.

It may also be possible to better target a fiscally neutral RBT by introducing 3 differently priced blocks rather than the 2 we have currently modelled. A third high-premium block could kick in at the very highest level of consumption to target households in the top 2 income deciles. This would reduce the premium levied on the middle block, protecting low-income households that might consume just above the ‘essential’ threshold.

However, even with protections in place, a fiscally neutral RBT will always produce some losing households. Our assessment is that the balance of losses to gains in this model renders it politically undesirable.

An alternative: A hybrid funding model

A hybrid funding model that combines external funding with cross-subsidy within the billing system significantly improves the balance of losses to gains while also reducing the level of additional subsidy required.

We modelled an RBT that uses a combination of premiums and £2.5 billion of subsidy to reduce the average energy bill by £86 a year. Our modelling is based on the following parameters:

| Means-tested and disability benefit protection | Universal allowance kWh per week | Allowance per child kWh per week | Unit rate discount on lower block (%) | Unit rate premium on higher block (%) | Bill saving for median household | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electricity | Y | 40 | 10 | –9 | –7 | £86 |

| Gas | Y | 104 | 25 | 10 | 3 |

As Figure 18 demonstrates, winning households in decile 1 could see their bills come down by £125 a year, while winning households in decile 5 would see a bill decrease of £97 annually.

An RBT would also increase the efficiency with which the £2.5 billion is distributed, particularly at the top of the income distribution.

Figure 19 shows that 31% of households in decile 10 would pay an additional £65 on their energy bills, which would help to deepen savings for households lower down the income distribution. While a hybrid approach still produces some losing households further down the income distribution, the scale of these losses is far more tolerable than in an RBT funded entirely from within the billing system. Raising money via bills will always be less optimal than doing so via general taxation.

However, even a hybrid approach requires a significant level of external funding. There are 2 main options worth considering when looking for sources of this funding.

Network profits

Citizens Advice and the think tank Common Wealth have long argued that the UK’s transmission and distribution network operators (both gas and electric) have been making excess profits.

While Ofgem sought to tighten these margins following criticism in 2022, analysis by Citizens Advice in 2025 suggested that operators have once again collected outsized returns worth around £4 billion over the period 2021 to 2024 (Citizens Advice, 2025). Against an allowed equity return set by Ofgem of 5.3%, loopholes have allowed electricity distributors to access returns approaching 14.3%. Electricity transmitters achieved returns of 10.5% compared with an allowed return of 4.5%, while gas distributors and transmitters have achieved 8.5% and 6.1%, respectively, over the regulatory period to date. Much of this outperformance derives from gains made thanks to lower-than-expected debt interest rates.

At around a billion pounds a year, this windfall is significant and could be usefully spent supporting an ambitious energy affordability scheme. A windfall tax on network operators, implemented via a higher rate of corporation tax, could help to raise funding that could be funnelled into an RBT. This would likely represent a temporary solution ahead of any regulatory changes from Ofgem to amend the loophole that is enabling excess profits. However, given the likely decrease in energy bills in the next 10 years, a temporary source of revenue generation may in fact be appropriate.

Public attitudes

This approach is not without political challenges, particularly given the role that network operators will be expected to play in delivering the network upgrades that will enable clean power 2030. However, it does reflect a strong current in public attitudes. Recent polling from More in Common (2025) found that 70% of Britons think energy suppliers are either almost entirely or somewhat responsible for high energy bills, and 64% say the same for energy generators. These results were echoed by participants in a series of focus groups we ran. Respondents, who had been categorised as rooted patriots, progressive activists, established liberals and traditional conservatives, all identified energy profits as an issue when discussing energy affordability.1 This sentiment creates opportunities for policy-makers to think more critically about the role that energy profits could play in funding energy affordability support.

General taxation

Funding interventions to reduce the cost of essential energy through general taxation is more progressive than through energy bills. There is a typical energy consumption gap between households in the bottom and top equivalised income deciles of around 30%. By comparison, households in the top equivalised income decile pay 25 times more in income tax than those in the bottom decile (the ratio drops to around 8 times when looking at the second highest income decile).

As explored, funding interventions through general taxation also avoids the issue of creating large losses amongst specific low-income households that have high energy costs.

There are clear pressures on government finances, and Labour has made a manifesto commitment not to raise the main rates of income tax, National Insurance contributions and VAT. However, there are ways to raise more tax revenue in ways that are fair and efficient. For example, by bringing effective tax rates on capital gains more closely into line with income tax or applying National Insurance contributions to investment income.

The Government needs a clear long-term plan for improving living standards, and significant investment in an energy affordability mechanism would be one obvious way of achieving that.

6. Implementation

An RBT funded through a combination of general taxation and network profits avoids some of the significant implementation challenges faced by a fiscally neutral version of the policy.

A fiscally neutral RBT relies on a cross-subsidy between high and low consumption households, and there are several ways that cross-subsidy could break down.

One way of understanding this risk is in relation to the differences in consumer profiles between suppliers. Suppliers with a higher proportion of low-consumption households might be faced with a choice between not recouping the costs associated with delivering the discounted unit rate or charging such a high premium on high-consumption households that they would no longer be able to offer competitive tariffs. Another iteration of this challenge relates to consumer switching. If an RBT were only applied to default tariffs via the price cap, high-consumption households would have a significant incentive to switch onto fixed-term tariffs. This would not be a problem if they were switching to fixed tariffs held by the same supplier because the supplier could use their discretion about how to recoup the costs of the discounted rate, whether from a premium on default tariff consumers or a premium on fixed tariff consumers. However, if high-consumption households all moved to fixed tariffs held by just 1 or 2 suppliers (and suppliers would have a significant interest in competing for these consumers), it would present a problem.

One approach to navigating this challenge would be for Ofgem to establish a cross-market reconciliation mechanism, similar to the system created to help level pre-payment meter and direct debit charges. This would allow suppliers to be reimbursed or charged depending on the profile of their consumers.

This process is far simpler if the discounted essential block of energy is funded from outside the billing system. It would simply require the Government to offer a rebate to energy suppliers based on the number of consumers they have and how much of the essential block they consume. If a hybrid RBT were implemented, a system of redistribution similar to the one outlined above would be necessary, but reducing the amount of money being recouped by the premium would lower the administrative burden placed on Ofgem and suppliers.

Net zero

An externally funded RBT also simplifies the interaction between the RBT and decarbonisation policy.

While a fiscally neutral policy that charges more for high levels of consumption discourages wasteful energy use, it also introduces complexities in relation to incentives around electrification. Namely, charging a premium on high levels of electricity consumption could increase the cost of adopting EVs and heat pumps, both of which are central to the Government’s approach to decarbonisation.2

However, while a blanket increase in cost for high levels of energy consumption may be undesirable, the RBT could be designed in a way to disincentivise particular types of high consumption — namely, gas.

Under the current system, policy levies primarily fall on electricity bills – artificially elevating their cost in relation to gas. The Government is currently considering how to address this imbalance. Some have proposed moving policy costs into general taxation (Marshall, 2025). The total cost of paying for social policies, the feed-in-tariff and the renewables obligation would amount to £4.3 billion a year (though this cost would fall over time).

If the Government wanted to maximise the impact of this spending, it could combine moving some policy costs into general taxation with an RBT to help distribute the remaining costs fairly. The logic is like that used in the hybrid funded model, whereby a small premium is used to generate additional funding in a progressive way. If a premium were introduced only on gas consumption above a certain threshold, it would also disincentivise high levels of gas consumption and encourage the adoption of low-carbon heating technology.

This approach would need to be assessed over time as increasing numbers of households transition to electricity-only heating systems, but it demonstrates how an RBT could be used flexibly to support the transition to net zero.

7. Conclusion

Every household should be able to meet its essential energy needs and have access to the affordable energy it needs to flourish. The current energy system is failing to deliver these outcomes, and the Government does not have the tools necessary to intervene. Support for those on the lowest incomes is vital, but there is a significant number of households further up the income distribution that are also struggling to heat their homes.

To capture both the breadth and depth of need, support must be distributed in a progressive way that reaches those beyond the benefits system. The RBT provides a mechanism for achieving this, without constructing a new system of income-based data matching. However, it is not without limitations. Designing a fiscally neutral RBT produces intolerable numbers of losing households with significant redistributive inefficiencies at the top and bottom of the income distribution. When combined with external funding, however, it is possible to unlock the progressive potential of the RBT – helping to protect low- and middle-income households in a relatively efficient way through a single system.

£5 billion of funding would provide a bill discount of £150 for the median household, with low-income households receiving slightly more and high-income households slightly less, on average. This is a significant level of government spending, but it is not the only way the RBT can operate. We have demonstrated the impact of a range of funding levels and how they can be combined with cross-subsidy within the billing system to deliver different distributions of winning and losing households. When comparing a range of policy options — including a cut to VAT — the RBT maximises progressivity.

Targeting excess profits currently generated by network operators is one option for funding some of this support, but general taxation remains the most progressive and sustainable approach. Significant investment in an energy affordability mechanism should be a core part of the Government’s approach to improving living standards.

This is a time of considerable change in the energy system, and households must be supported throughout the transition. The Government needs a flexible policy lever that will allow it to respond to changing wholesale and policy costs while continuing to meet households’ needs. Introducing an RBT in the gas market to help progressively distribute some of the costs of rebalancing could be one place to start.

The RBT is a flexible tool that can respond to different levels of external funding in ways that vary the depth of support available and the level of cross-subsidy within the energy billing system, all while delivering progressive outcomes to the majority of households.

Methodology

IPPR rising block tariff model

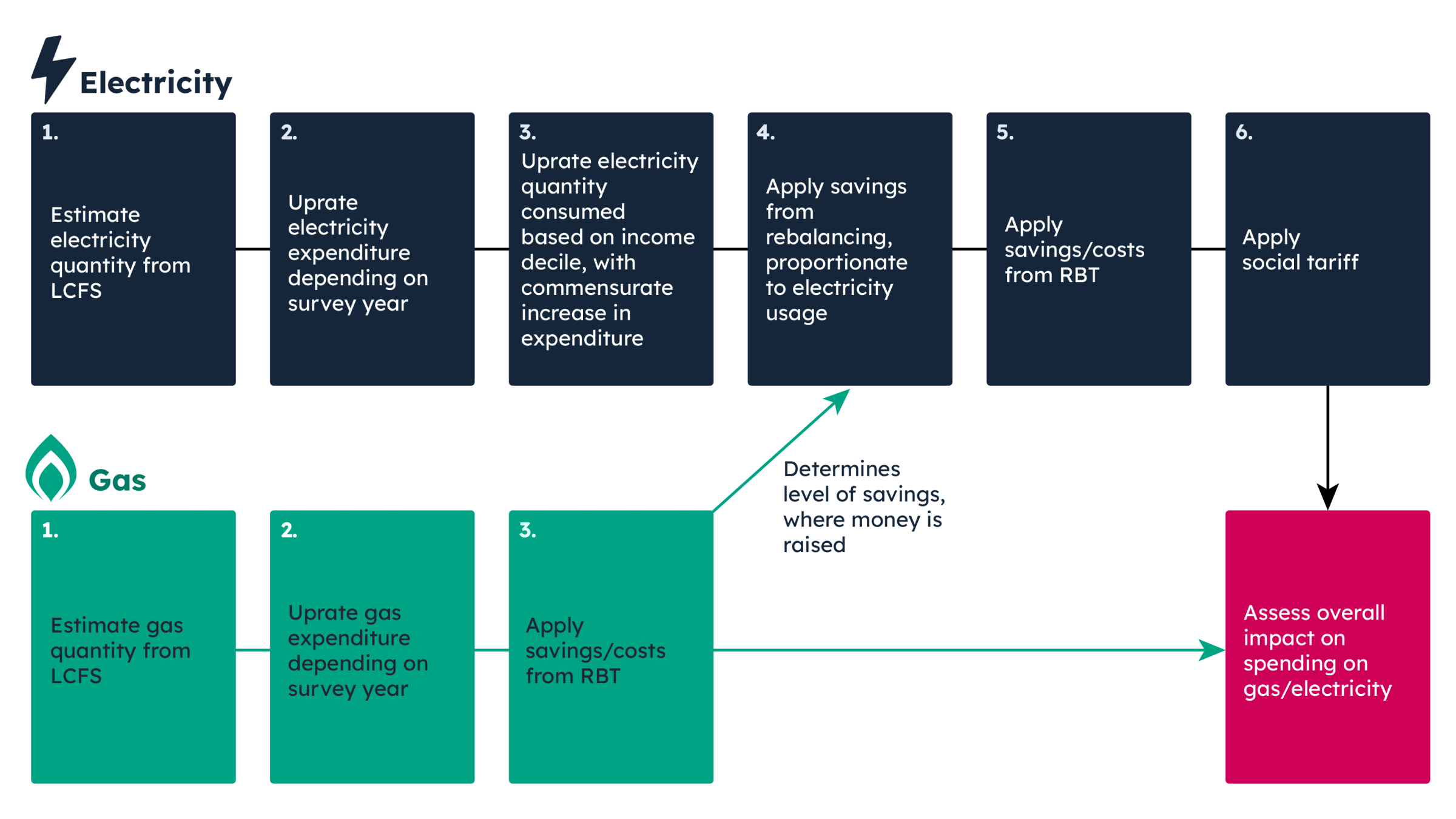

Electricity modelling

Step 1: Estimate electricity quantity from Low-Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS). We estimate the electricity usage for each household based on LCFS expenditure data, with different assumptions applied for the unit cost depending on the survey year.

Step 2: Uprate electricity expenditure depending on survey year. As we pool results, energy expenditure has been different in different years, so we need to apply different levels of uprating depending on the survey year in accordance with the Consumer Price Index (CPI) electricity series.

Step 3: Update electricity quantity consumed based on income decile, with commensurate increase in expenditure. We then increase electricity usage by a fixed amount dependent on the household income decile to capture likely future electricity usage, with greater increases for higher income deciles as follows:

| Income decile | Electricity quantity consumed |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1.7% |

| 2 | 1.7% |

| 3 | 2.2% |

| 4 | 2.2% |

| 5 | 9.2% |

| 6 | 9.2% |

| 7 | 8.2% |

| 8 | 8.2% |

| 9 | 19.3% |

| 10 | 19.3% |

These data reflect the take-up of electric vehicles (EV) expected over the course of the parliament. Industry forecasts of EV sales were distributed across quintiles using data from the LCFS survey on household expenditure on new cars. An adjustment is then applied to account for the fact that higher-income households also buy more expensive cars. Once the forecast number of EVs in each quintile/decile is established, the additional electricity consumption of EV-owning households is modelled using National Travel Survey data on annual car mileage by household income quintile and industry data on EV energy efficiency.

We then increase uprate spending commensurate to the increase in the quantity.

Step 4: Applying savings from electricity re-balancing (raised from Gas RBT).

- We calculate total modelled annual energy usage in model (weekly usage x household weights, added up across all observations x 52).

- Take the amount raised by the gas RBT (subtract any revenue which is ‘extracted’ for other purposes if applicable) and divide through by total modelled annual usage to get saving per kWh per week.

- Apply that to all households in the data – so households with higher consumption get higher savings.

Step 5: Applying savings/costs from RBT.

The thresholds, discount and premia rates are set by the user, but a goal-seek type approach can be used to target certain levels of spend/revenue – either (i) holding the premia constant, it will calculate the discount required for a given choice of total spend or (ii) holding the discount constant, it will calculate the premia required for a given choice of spend.

We also include functionality, switched on in most scenarios, for households on means-tested benefits or disability benefits to get the full discount rate across all of their consumption (for example, whether U>A or U<A).

Step 6: Apply social tariff . If switched on, this can provide a fixed discount converted to a weekly amount for households in receipt of means-tested benefits, disability benefits, or with incomes below a set threshold.

What about for gas?

The methodology and logic are identical for the gas tariff. In our model, if the gas RBT is configured to raise money this can be used to fund making electricity cheaper (as in step 4 of the electricity modelling). We include functionality to syphon off some or all of the revenue so that it doesn’t make electricity cheaper (for example, to pay for something outside of the model).

Notes

- All of the groups which took place as part of this project were conducted online by More in Common in August 2025. Recruitment was based on a mixture of demographics, voting history, geography and segment allocation. More information on More in Common’s 7 segments can be found in The seven segments of Britain, by More in Common.

- There are several approaches that could be taken to better align an RBT that places a premium on high consumption with the adoption of low-carbon technology. One would be to bundle energy efficiency measures so that households can add new electricity loads (EV charging, heat pumps) without proportionally increasing net grid consumption under an ‘energy-as-a-service’ model. Another approach would be to include additional allowances or adjustments for technology adoption within the RBT to avoid discouraging beneficial electrification. The New Economics Foundation, for example, has outlined a proposal for how households off the gas grid could receive a larger low-cost electricity allowance so they are not unfairly penalized for heating electrically (Chapman and Kumar, 2023).

References

Chapman, A. Kumar, C. (2023) The National Energy Guarantee

Citizens Advice (2025) Energy network companies pocket £4 billion in excess profits from cost-of-living crisis

End Fuel Poverty Coalition (2025) Ofgem Price Cap

House of Commons Library (2025) Domestic energy prices

Joseph Rowntree Foundation (2025) UK poverty 2025

Marshall, J. (2025) Splitting the bill

Milne, B. et al., (2025), A year of Labour but no progress: JRF’s cost of living tracker, summer 2025

More in Common (2025) The seven segments of Britain

More in Common (2025) Britain's high energy bills: The permacrisis that keeps on burning

Norman, A. et al. (2025) Closing the fuel poverty gap: A plan for targeted energy support

Nuffield Politics Research Centre (2025) Addressing key voters' economic insecurity is vital for all parties

Ofgem (2025) Average gas and electricity usage

Ofgem (2025) Debt and arrears indicators

Shepheard, M. (2025) Is removing VAT really the best way to cut energy bills?

SMF, Citizens Advice, Public First (2024) Future of energy bills

Wright, O. Vaughan, A. Bradley, S. (2025) Revealed: Global warming exaggerated, say soaring number of Britons

Acknowledgements

Research, investigation and analysis – Tilly Cook, Andrew Wenham

Writing – original draft – Tilly Cook, Alex Chapman (The New Economics Foundation)

Writing – review and editing –Darren Baxter, Maddy Moore, Chris Belfield, Alfie Stirling, Peter Matejic, Ann Crossley

Data visualisation –Andrew Wenham, Isobel Richardson

How to cite this briefing

If you are using this document in your own writing, our preferred citation is:

Cook, T. Wenham, A. (2025) Energy affordability: how to reduce bills for majority of households. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

This briefing is part of the cost of living topic.

Find out more about our work in this area.