Pathfinders: learnings from 2 years of supporting future-building practice

How can we nurture an ecosystem of organisations who are prototyping alternative futures? How can funders serve this work, both inner and outer transformation?

Paying attention to other worlds

Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing.

Arundhati Roy

In early 2023, JRF shared its first steps in resourcing a network of organisations doing the deep, hard work of transforming systems. This strand of work, called Pathfinders, was part of the wider Emerging Futures 2-year learning cycle across 2023 and 2024. As this cycle comes to an end, I want to reflect on the things we’ve learned, questions we’ve asked and tensions we are sitting with. Writing this has felt harder than I imagined, because seeking to pattern something differently within philanthropy involves confronting all the unjust systemic barriers that keep the existing paradigm tethered in place - whether that is governance, organisational design, culture, legal agreements, relationship patterns, power dynamics, mental models and our collective neuro-biological responses.

When change is complex, relational and messy, it can be hard to know how much to share, what’s useful, and where the boundaries are. I’ve written this blog as an attempt at working in the open, taking accountability for our choices, being transparent about our learning, and hopefully sparking further conversation.

In Joseph Rowntree’s 1904 memorandum, he reflected that much of the current philanthropic effort is directed to remedying the more superficial manifestations of ‘weakness’ or ‘evil’, while little thought or effort is directed to search out their underlying causes. Over a hundred years later, the Pathfinders strand of work was set up with similar intent - to resource organisations who are actively designing, building and demonstrating alternative futures anchored in liberatory and regenerative principles. Their work is propositional and brings new visions to life; it sits alongside and is complementary to work that opposes violent and unjust systems through resistance.

For some examples, have a look at We Can Make’s innovative community-led housing model, Onion Collective’s approach to regeneration in place, Healing Justice London’s work on building capacities and infrastructures to support community-led health and healing, Open Systems Lab’s projects on transforming land ownership, Stour Trust’s work on community asset ownership, Bioregional Learning Centre’s work on climate resilience across South Devon, Library of Thing’s model for making borrowing better than buying, Resolve Collective’s work on providing platforms for new knowledge and ideas, and Land in Our Name’s approach to land justice through reparations.

There is a growing movement of such organisations across the UK, who are shaping societal transition by disrupting and innovating at the edges. As Gal Backerman explores in his book The Quiet Before, change comes not only in the loud cry of revolution but also in the quiet exchanges about new ideas and the careful, experimental work to develop new practices, ready to emerge when the time comes.

Recognising that this type of work can be often misunderstood and poorly funded, the Emerging Futures team wanted to support it through funding, power-building and platforming. Sophia Parker and Cassie Robinson initiated the programme in early 2023 by identifying an initial group of Pathfinder organisations based on a defined set of characteristics informed by research and dialogue, and Cassie’s work on the Growing Great Ideas programme at the National Lottery Community Fund. They wanted to identify organisations who were acting as important “nodes” (places where multiple flows or connections intersect) within the wider field. I joined JRF a few months after this work was initiated and took on a stewardship role, with the intention of helping to unlock the enormous potential within this work.

What worked well

We need to move from competitive ideation, trying to push our individual ideas, to collective ideation, collaborative ideation. It isn’t about having the number one best idea, but having ideas that come from, and work for, more people.

Adrienne Marie Brown.

We start by sharing the patterns we think worked well and are worth replicating. But none of these were without significant challenges and tensions, which we explore in the next section.

Speed and Flexibility

The strong conviction behind this work was that it is important for funders to move money quickly and learn by doing, instead of having lengthy, over-engineered internal strategy processes. The movement of money (grants of either £55,000 or £33,000 depending on organisational maturity) was quick, offered as core funding instead of short-term project funding, and did not come with burdensome reporting requirements. Many organisations said this was a breath of fresh air, and allowed them to invest in what was most important to them.

Working through emergence

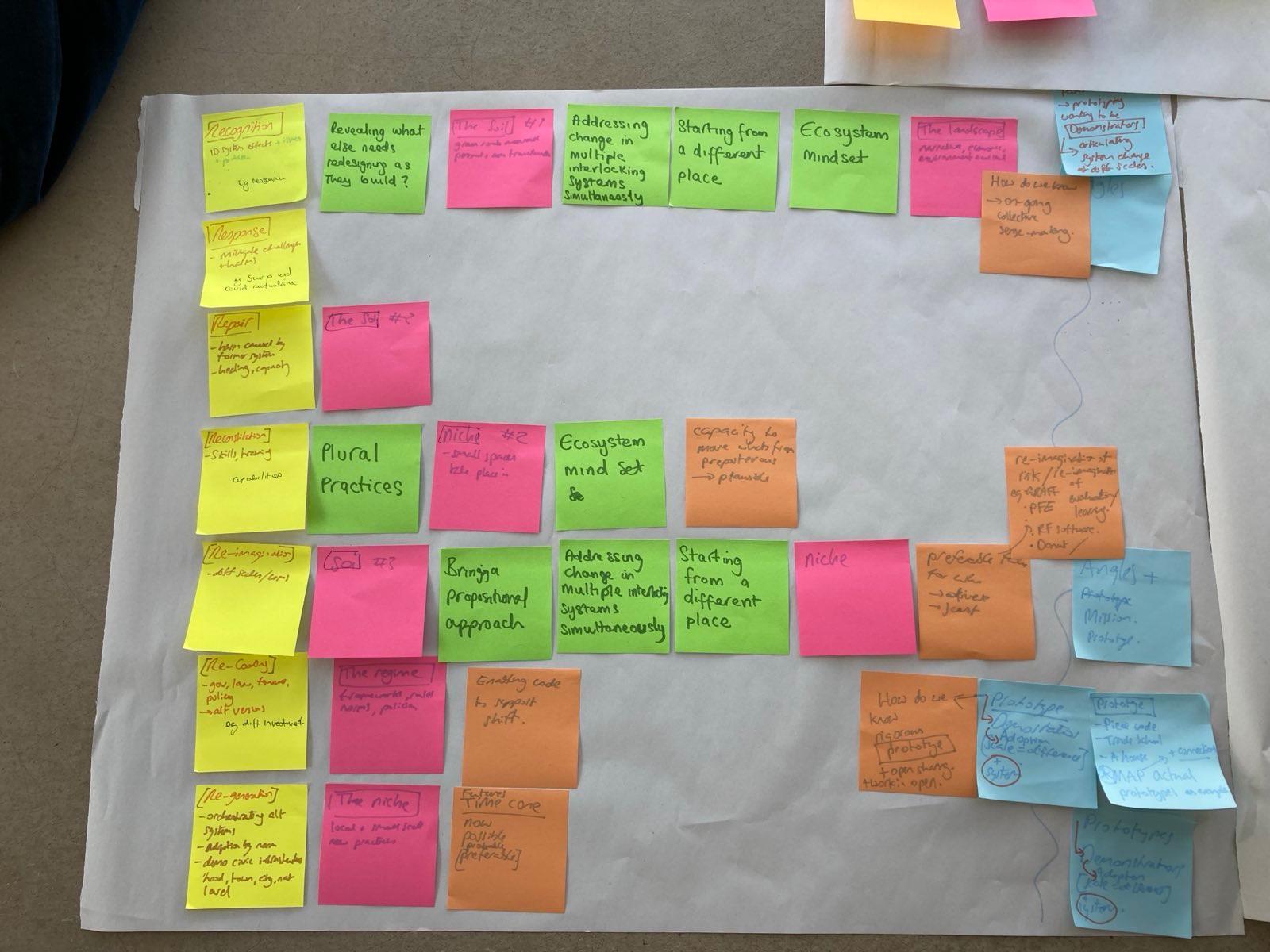

The broader intention behind this work was to create a space where relationships and trust could be built, patterns and synergies identified, and emergent opportunities could be explored together. Rather than having a requirement for organisations to report to JRF on their activities, we were keen to foster spaces for peer learning and reflection that might contribute to this whole being greater than the sum of its parts. We were deliberate about creating opportunities for relationship-building and sensemaking, including hosting monthly online calls; a large, 2-day in-person gathering at Hawkwood College in autumn 2023; and a couple of smaller in-person co-creation sessions in 2024. We learned and adapted with every step of the process. We got increasingly comfortable with uncertainty and learned to trust that it was good enough to identify the next best step, in a context where so much is unknown.

A good example of leaning into emergence was the seed sown by some organisations at the Hawkwood gathering for this group to co-create a proposal for unlocking significant additional funding (from multiple sources) into the alternatives-building field. This was followed by a huge amount of co-creative work to develop a proposal over the past year and to seek approval from JRF’s trustees. This work is still in progress and we plan to share more about it later in the year.

Engagement and support of JRF trustees

One of the enablers of our approach has been a tremendous amount of internal work with JRF’s trustees. The trustees have been on a comprehensive, challenging, externally-facilitated journey of inquiring into what this moment in history asks of them and the best way for JRF to uphold its duties as a well-endowed foundation. Due to regulatory requirements, trustee roles are unpaid and often carried out on top of full-time work and personal commitments. This doesn’t create the kind of engagement space that deep transformation calls for. JRF’s trustees have been generous with their time, and brought curiosity, challenge, a willingness to be challenged, and openness to thinking in nuanced ways about entrenched concepts such as ‘risk’ and ‘fiduciary duty’. But of course, this work is far from done. These conversations are ongoing as part of a much bigger transformation journey within JRF as it reorients its strategy, governance and endowment allocation approach.

Facilitative stewardship

I joined the JRF Emerging Futures team when the Pathfinder group had been identified, but the work was at a very early stage, full of uncertainty. In the beginning, it was hard to hold my need to better understand the context and relational dynamics, with a sense of wanting to move quickly and offer value. When work is complex and nascent, one can’t look to a job description and traditional structures for clarity. I shaped my role in line with a broad intention of supporting and serving an ecosystem, and bridging between this and JRF’s future direction. I think it helped that I don’t have a grant-making background, and have spent many years working on relational and systemic change, where adopting a posture of humility, strategic orientation, and active partnership is key.

Most of my work involved listening deeply; noticing needs, patterns and dynamics; connecting dots; hosting gatherings; offering funding to resource early emergent ideas; advocating for this work and actively navigating a path between the Pathfinders’ ideas and JRF’s governance, in close partnership with Sophia. Of course, this was not a linear and comfortable process by any means, and involved reckoning with my privileges of being in a funder role, balancing multiple identities especially as someone from the Global Majority, confronting my limitations and blind spots, and grappling with complex power dynamics. After the first year in this role, I realised what I was trying to do was to experiment with how someone wearing a “funder” hat could show up as a collaborator within a group process- a postural shift I think is necessary if we want to move into a “power-with” paradigm.

What was challenging and could be different?

Nourishing and healing communication is the food of our relationships.

Thich Nhat Hanh

More deliberate approach to ecosystem-building

The original framing of this work called the Pathfinders an ‘ecosystem’, but in hindsight this was premature, and implied a false sense of coherence before trust had really been built. It was more accurate to say this was a ‘portfolio’ of organisations with varying levels of trust and relationship between them. As convenors, we should have paid more attention to the fact that there were very different kinds of backgrounds, experiences, relationships and fluencies across the group. In such a context, creating the conditions that allow an ecosystem to form takes significant work as well as time, which we underinvested in. This work not only requires structures and deep skills which are vitally important (e.g., facilitation, communication, community-building and so forth) but also enough spaciousness for connections to spark organically without feeling over-engineered.

On reflection, we did not have a sufficiently deep process from the beginning for building trust, aligning values and intentions, establishing community agreements and decision-making processes, openly exploring rank dynamics, agreeing how to handle differences and conflict, and navigating the line between cohesion and independence, structure and emergence. Working at the speed of trust in the face of rampant urgency culture, requires neuro-biological change in habits and intentional culture shaping- it cannot just be verbally willed into existence.

JRF could have also been clearer at the beginning that receiving Pathfinder funding came with a clear invitation to participate in kinship, cross-pollination and helping to grow the wider field. This was not made explicit in the beginning and caused some confusion and mismanaged expectations later on.

We have learned that when co-creative processes are left too open-ended, they can reinforce existing power dynamics and systemic inequities, such as it being hardest for the smallest and most under-resourced organisations to have the capacity to contribute. Too much of a vacuum also creates risk for people who stick their heads above the parapet and take on leadership roles, often carrying the majority of the cognitive and emotional labour without receiving adequate support and recognition. When there isn’t sufficient relational infrastructure across the whole group, it places disproportionate burdens on certain people and weakens the potential of the whole. In hindsight, it would have been helpful to have significantly more facilitation capacity and being really nuanced about what types of facilitation and process-holding skills were needed at different stages of the work. This is something we are actively addressing now.

Deeper data and insights to inform curation

We’ve always known that the organisations funded through Pathfinders are not the only ones doing this kind of work. In 2024, JRF commissioned Onion Collective to carry out research into the wider alternatives-building field that Pathfinders sit within.

This research showed that there is a network of around 2,000 organisations working to build alternative futures in a thousand different, hopeful, committed, future-seeking ways. According to the research, the Pathfinders do play important ‘“nodal’ roles within the field, but there are also other organisations playing such roles and contributing to the field in vital ways. Going forward, we are thinking about how future funding, both from JRF and other wealth-holders, can flow to a wider range of organisations, enabled through peer-led and distributed decision-making (as opposed to top-down funder-led decision making.

JRF chose the Pathfinders as a diverse range of organisations (based on size, skills, maturity, type of work and so on). There is a beautiful upside to this in terms of fostering flows and exchanges between groups who might not be otherwise connected and enabling mutual support and mentorship between organisations at different stages in their evolution. The downside is that it makes it harder to cultivate coherence when trying to build something concrete together, because of vastly different day-to-day realities. We’ve learned that when it comes to co-creating together, having sub-groups of more contextually similar organisations, as well as a fluid and dynamic approach to how groups organise around specific, time-bound intentions is important. Paying attention to group size is also critically important as different sized groups work better for different purposes. Here I find Priya Parker’s guidance on numbers really helpful.

Funders doing the deep work to show up as collaborators

As many of us have experienced in recent years, there is an emerging trend within philanthropy from one extreme of power hoarding to the other extreme of wanting to hand over power entirely, which can be equally damaging. It can shift the burden of labour to groups who are already carrying the most risk and responsibility. I’ve definitely grappled with this tension, and believe it is felt more broadly within the funding field too. It can show up as a sense of unease and tentativeness in decision-making, fears about speaking openly or taking up too much space, concerns about being seen only as a ‘funder’ rather than a multi-dimensional human being, and sometimes genuinely not knowing what to do next.

In addition, it can sometimes feel like there is an ocean of unspoken dynamics present in the work that go unnamed and are hard to grapple with - everything from deep discomfort about philanthropy’s embeddedness in colonial systems, conditioned fight, flight and freeze responses in our nervous systems, to feelings of imposter syndrome, not belonging, and facing the grief that is part of confronting the multiple crises we are all grappling with.

Our experience has shown that moving into a ‘power-with’ paradigm requires us to lean into the deeper work of collective healing, at personal, institutional and systemic levels. What are the embodied capacities needed to enable transformation at the level of self, organisation and system? I have found myself returning to this question again and again in this work, learning to “live the question” as poet Rilke invites us to.

It feels critically important to cultivate dedicated spaces that develop self-awareness, skills, and embodied capacities for all of us to be able to show up empowered in this work, without shrinking or hiding. Personally I don’t think I could have stewarded this complex and messy work inside JRF, without the incredible coaching I received from Nkem Ndefo (founder of Lumos Transforms and creator of the Resilience Toolkit), participation in the Politicised Somatics course by Staci Haines, support from my informal network of peers/mentors, and my grounding in deep spiritual practice.

How do we make such transformative spaces more accessible for practitioners across the field is a key question we hope that many funders are thinking about. For more on these themes, do have a look at the brilliant guide by Resourcing Racial Justice.

Bridge-building within and beyond philanthropy

The Pathfinders strand was always intended to be just a starting point. The wider aim is to unlock significant additional resources for the work of building alternative futures, both from within JRF and from other wealth-holders. The Pathfinders track sat alongside another stream of work that focuses on transforming wealth to enable people and planet to flourish. JRF has a big role to play going forward in contributing to alignment between these different worlds - the world of people building alternative futures, the wealth-holders who want to move their resources in service to this, and the much-needed intermediaries who can facilitate trust and the flow of resources between these groups. The challenge and opportunity for JRF is to demonstrate how a large institution can both transform its own strategy, culture, governance, investment model and processes from within, while also contributing to these broader shifts in the field, and doing so at a pace that is congruent with the polycrisis we are living through. This is the work of many more years to come.

Concluding thoughts

Stewarding this work over the last couple of years has been an incredibly challenging, eye opening and enriching journey. This blog was focused on looking back, while a future blog will focus on what’s next. Some patterns have consistently shown up, raising questions that I think we need to collectively grapple with as part of the work of building regenerative futures.

We're looking at how we might:

- honour the need for pace and speed without collapsing into urgency culture

- know when to be directive and clear versus open and emergent

- hold personal identities fluidly, as well as being fluid about an organisation’s role (for example, funder, field builder, participant within an ecosystem, advocate)

- confront the ways modernity and extractive systems live inside us, and view internal and external change as one

- unlearn performative behaviours so that new authentic possibilities can open up

- cultivate the art of blending different kinds of knowledge within a change process - technical, financial, governance, spatial, emotional, relational, spiritual

- prioritise learning and reflective practice as a core strategic muscle

- name and engage with power dynamics skilfully

- create a culture where differences, half-baked ideas, mistakes and generative conflict is normalised

- remember to celebrate when we can, to cultivate joy, to see ourselves as part of a much bigger picture spanning generations.

I hope these reflections, offered in the spirit of transparency and generosity are helpful, especially for others seeking to bring about deeper change within the funding landscape and experimenting with third horizon work. I’d love to hear what resonates, and what questions, thoughts or challenges this brings up.

This reflection is part of the imagination infrastructures topic.

Find out more about our work in this area.