Talking about wealth inequality

Looking at perceptions of, and attitudes towards, wealth and wealth inequality — and how to increase public support for a fairer distribution.

- Executive summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Introducing the frames

- 3. Pre-existing attitudes to wealth inequality

- 4. The effects of the frames in detail

- 5. Results commentary

- Annex: Experimental and focus group design – technical notes for readers

- Methodology and results appendix

- Notes

- References

- Acknowledgements

- About the authors

- How to cite this report

- Executive summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Introducing the frames

- 3. Pre-existing attitudes to wealth inequality

- 4. The effects of the frames in detail

- 5. Results commentary

- Annex: Experimental and focus group design – technical notes for readers

- Methodology and results appendix

- Notes

- References

- Acknowledgements

- About the authors

- How to cite this report

Executive summary

Recognising wealth inequality's harmful effects, and mindful of the need to increase its public and political salience, social change actors are increasingly engaging with wealth inequality as centrally implicated in reproducing unjust systems – systems marred by poverty as well as gender, racial, economic and environmental injustice. This renewed drive to tackle wealth inequality led to a need to understand how the way we talk about it affects public and political mindsets, and how these mindsets need to be taken into account in the design of campaigning strategies.

We've found that people have strong pre-existing opinions about wealth inequality. The majority of people already think the gap between the richest and the poorest is too large, would like to see wealth more evenly distributed, would like to see higher taxes on rich people, and want to see more spending on welfare benefits.

People hold more mixed views about the role of wealth in society more generally, and are fairly pessimistic about politicians and the political system. There are systematic variations within these public attitudes: grouping by income, voting history and sex reveals different attitudes to wealth, redistribution and politics more generally. But this report shows you that the way you talk about wealth inequality can demonstrably shift attitudes and opinions.

This resource is for you if you work in social change and want to know ‘what works’ to make people view wealth inequality more critically, and be more supportive of redistribution. The key aspects are summarised here:

Frame effects

The Unfair Influence frame: Exposing people to information (a ‘frame’) which highlights how wealth can lead to Unfair Influence in UK politics increases a range of critical orientations to wealth inequality: People are more likely to think the gap is too large, more likely to think that wealth use has a negative impact on society, and less likely to think that wealth is a result of hard work and talent. Exposing people to this Unfair Influence frame also makes people more likely to support redistribution in general and more likely to support increased taxes on the rich.

The Anti-meritocracy frame: Exposing people to information that undermines the idea of meritocracy by suggesting that wealth can buy a ‘head start’ increases a range of critical orientations to wealth inequality: People are more likely to think the gap is too large, more likely to think that wealth use has a negative impact on society, and less likely to think that wealth is a result of hard work and talent. This Anti-meritocracy frame has the strongest effect out of all the frame treatments on undermining the belief that wealth is a reward for hard work.

The Hoarding frame: Exposing people to information that suggests some people are hoarding wealth and starving our economy of what it needs to thrive, increases some critical orientations to wealth. People are less likely to think that wealth is a result of hard work and talent.

Although the Unfair Influence frame has the strongest overall effect, it is also alone in affecting attitudes to political context. It lowers trust in politicians and it reduces satisfaction with democracy. We have offered some suggestions for ways of mitigating this in the Results commentary.

Interpretation of results

The use of context-specific evaluations of wealth: The frames we describe in this report are based on context-specific evaluations of wealth (for example, good or bad uses, good or bad sources rather than good or bad wealth). We were aware in designing them in this way that they had the potential to distract from a more overarching (or ‘systemic’) assessment of wealth inequality. The focus on ‘uses’ and ‘sources’ had the potential to fragment our understanding of wealth inequality into different issues, or even to maintain space for defensive strategies by extreme wealth holders (such as increasing the focus on ‘good’ uses, like philanthropy). However, we found that leading on bad uses and sources as we did across the frames, then linking to a broader systemic analysis, worked to increase support for systemic solutions like redistribution.

Security, fatalism and trust: A key concern with ‘system is rigged’ or ‘unfair influence’ framing is that it can risk triggering pervasive fatalism: ‘I can’t see a way out of it’, for example. This could lead to a dampening effect on democratic engagement: if you do not believe that things can get better, why bother trying to make them so? We draw attention to the fact that despite our Unfair Influence frame affecting some political attitudes negatively, it also increased support for redistribution and higher taxes on the rich. And lower satisfaction with democracy is also a common predictor of increased political participation and mobilisation – which can end up being positive for democracy itself. It is important to recognise that this mindset about the system being rigged is dominant and needs to be engaged constructively. Failing to do so leaves it open to being co-opted by harmful far-right populist narratives.

Meritocracy and other system justifying beliefs: A key concern for social change communicators is the potential for frames to trigger strongly held ‘system justifying’ beliefs that are likely to decrease rather than increase support for change. Our results showed that it is possible to design frames that engage with and undermine meritocratic beliefs.

The importance of supporting evidence: In a topic like this, which mixes together factual claims and complex causal explanations, convincing evidence can play an important role. Our experiment highlighted that it is important not just to build effective supporting evidence into your frame, and bolster that with widely recognised expertise, but may also be necessary to generate new knowledge to fill the gaps where such evidence is lacking.

1. Introduction

The UK is a very rich country, but its wealth is not evenly shared. A few people have a lot and millions of people have very little or are in debt.

This acute inequality manifests in widespread economic insecurity, which is fuelling populism and making existing inequalities of race, sex and class materially worse.

But public engagement with wealth inequality is hampered by the fact that we do not necessarily recognise these effects on our day-to-day lives (the sense of our own economic insecurity, the awareness that some groups seem to be more insecure than others) as being in part a consequence of the fact that a few people have a lot.

Added to this, because much wealth is not visible to us as we get on with our daily lives, we tend to under-appreciate its scale, and relatedly, the magnitude of the gaps between richer and poorer groups. At the same time, measures to tackle wealth inequality tend to trigger strong opposition from those who feel they might lose out – typically the wealthiest in our society, but sometimes also those aspiring to escape insecurity in the future. Partly as a result of this, wealth inequality has low political salience.

What we wanted to find out

Is it possible to talk about wealth in ways that:

a) lead people to question whether the status quo is fair

b) increase people’s support for redistribution, whilst

c) minimising the impact on existing low levels of trust in government?

Our aim was to understand how exposure to different ways of talking about wealth inequality shifts the responses of respondents in 3 key areas:

1. Critical orientations: what works to shift people towards viewing wealth inequality more critically?

2. Redistributive preferences: what works to shift people towards viewing wealth redistribution more positively?

3. Political attitudes: do any of the frames work to shift people towards or away from trusting in politics and democracy?

The aim of the report is to provide you with practical tools for designing impactful communications strategies whatever solution (or combination of solutions) you might be working towards.

What we did

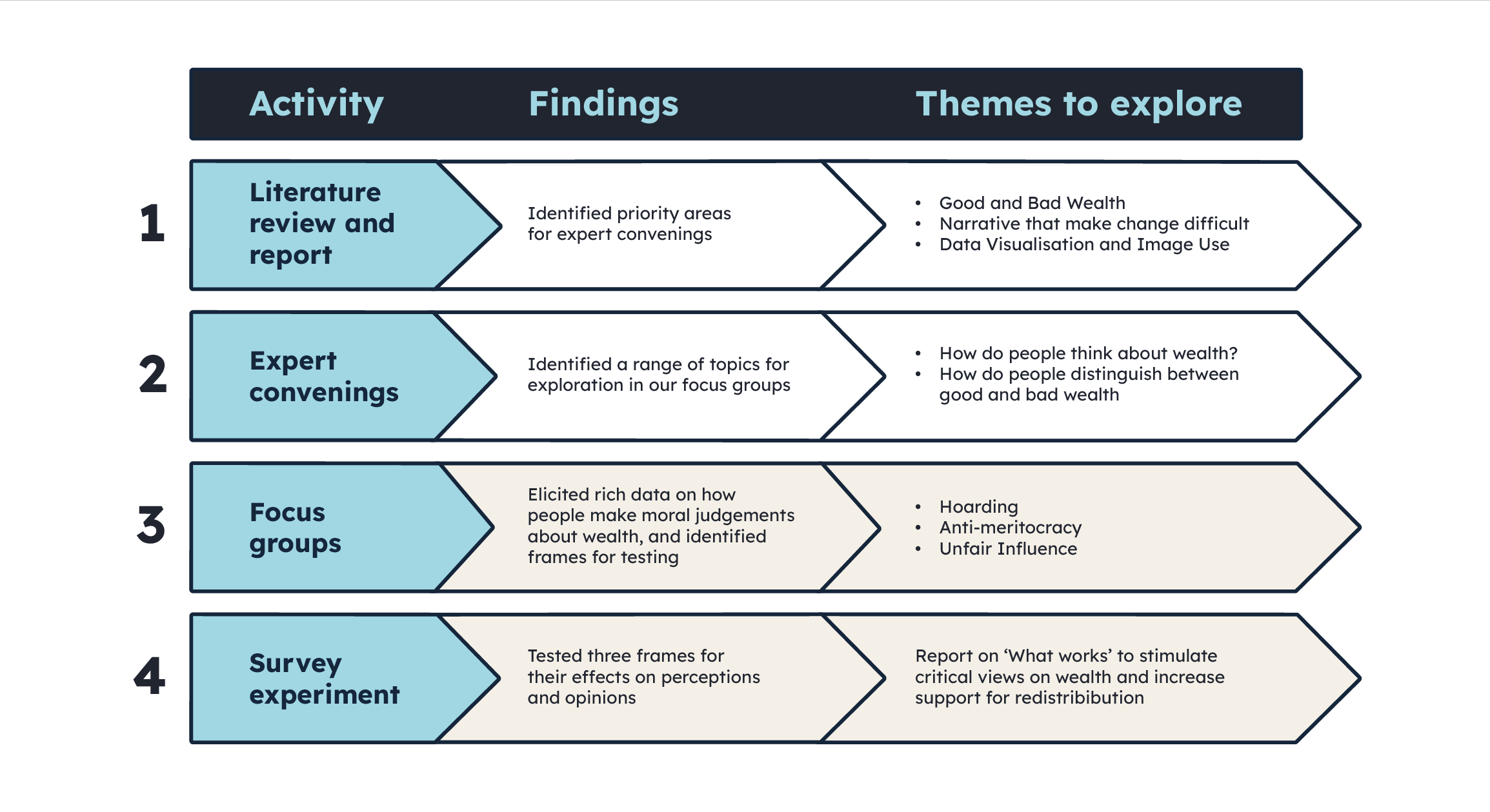

This report is the end product of a multi-stage collaborative research process, which has engaged the expertise and time of lots of different people and organisations. See the end of the report for more information about who has been involved. The outcomes of stage 1 can be found in this Joseph Rowntree Foundation report. In this report, we are sharing the results of stages 3 and 4.

We undertook focus groups with members of the public in London and York in autumn 2024 to understand perceptions of and attitudes towards wealth and wealth inequality. The conversations were broad ranging, from definitions of wealth, to views on what makes wealth good or bad, to trust in government and the media (see the Methodology and results appendix).

Based on the mindsets (how people think) and the opinions (what they think) observed in these focus groups, we developed a set of frames.1 Frames are a way of talking about an issue which defines the problem in a specific way, attributes a cause, makes a moral evaluation, and points towards a solution (Entman, 1993). We then exposed people to the frames in a survey experiment. This allowed us to test the effects of each frame against a control group.

The survey experiment took place in January and February 2025. You can read more about how we designed this experiment, and what factors we took into account in the Methodology and results appendix.

For both the focus group and the survey experiment, there is a short Annex at the end of this document that describes in brief what we did and how to interpret the results.

The comprehensive stand-alone Methodology and results appendix contains full details of parts 3 and 4 of the development process, descriptions of how we designed each stage, full results and results tables.

2. Introducing the frames

The text and image below each heading are the frames, presented in the same format used for participants in our survey experiment (including formatting, with no heading).

The Unfair Influence frame

Most people work hard and play by the rules. But the wealthiest people write the rules to suit themselves. They get rich from using their networks and then end up paying less tax than ordinary people.

A big part of the problem is that money can buy political influence:

- Research from the University of Warwick has found that political donations in the UK have more than doubled since 2001.

- Nearly a quarter of all recent nominations to the House of Lords were to political parties’ biggest donors.

That helps explain why billionaires on average pay just 0.3% tax on their fortunes, as shown in a report this year by the world’s biggest economies (the G20).

What mindsets is the Unfair Influence frame responding to?

The importance of sources and uses: How wealth is used was the dominant means of making ‘good/bad’ evaluations about wealth. The majority (57%) of good/bad evaluations made by focus group participants focused on the ‘uses’ of wealth. Source – for example whether wealth was ‘earned through hard work’ versus inherited, or stolen – was also important (as was source plus use).

Dislike of the use of wealth to buy political influence: Within this preoccupation with use, ‘buying power and influence’ was the type of ‘bad’ use that people felt most exercised about. ‘Buying power and influence’ accounted for 46% of all descriptions of bad uses of wealth. It was the only type of ‘bad use’ mentioned in all 4 groups.

Mistrust in government and systems: Forms of mistrust shaped conversations in all 4 focus groups:

- Mistrust in government as a result of perceived corruption was twice as common in right-leaning groups as left-leaning groups.

- Mistrust in government as a result of perceived incompetence and/or inefficiency was evenly expressed across all groups.

- Systemic mistrust, characterised by perceiving nefarious forces (‘global organisations’) as controlling the economy and our lives, was overwhelmingly expressed in the London right-leaning group.

Distinctions between ‘ordinary’ and ‘extreme’ wealth: The Unfair Influence frame mirrored the ‘us and them’ format of how systems mistrust views were often presented – pitting ‘the common man’ (or ‘most people’ in the frame) against ‘the people who run everything in the world’ (‘the wealthiest people’ in the frame). It drew on the distinction between ordinary wealth (that ‘most people’ have or aspire to) and extreme wealth (that ‘the wealthiest’ have).

Desire for fairness and dislike of tax avoidance: People expressed a distaste for unfairness when articulating possible solutions. The solution they mentioned most was ‘stopping tax avoidance at the top’. The Unfair Influence frame makes the case that the very richest are not paying their fair share. This will have resonated both with the desire to see fairness and the desire to stop abuse in the tax system. It will also have appealed to the positive expression of this view – that it would just be nice if we all had ‘a fair crack of the whip’. (York, right-leaning)

How are these mindsets evident in the way people talk?

Bad source + bad use + mistrust in government + distinction between ‘ordinary’ and ‘extreme’ wealth + desire for fairness:

“So I think there’s a huge difference between somebody that works hard, doesn’t exploit people, produces something that other people want, a service that people want to pay for or whatever and is ethical, demonstrates integrity. Then, the people that do the exact opposite, who sadly run everything in the world, which is ultimately owned by Vanguard, BlackRock and State Street. They control everything. So I think it’s how your wealth is acquired. For me, that’s the difference between good and bad wealth in very simple terms.” (London, right-leaning)

“You can donate money to the government to try and get things going your way. You get to set rules in your sector or wherever you are influential. Yes, you can get to set the tone of how things go more than someone else who doesn’t have wealth.” (York, left-leaning)

“Yes, I'm thinking when it’s anybody who’s wealthy, but that can use it to get out of something that an ordinary person wouldn't be able to.” (York, right-leaning)

“Yes, both UK, US, especially in the US, donations to political parties, especially in the US, tens of millions if not hundreds of millions, and you don’t make those donations if you don’t need a favour for something later on if that party was to get into power...” (London, left-leaning)

“His [Keir Starmer’s] bosses at the WEF, the BIS, they’re the ones, the unelected people. They’re the ones behind the scenes really running the show. Most of the people in parliament are absolute puppets following globalists or pretending to care about the common man. What a joke.” (London, right-leaning)

The Anti-meritocracy frame

The increasing power of wealth over hard work is creating an uneven playing field, especially for young people today.

- Family wealth allows people to send their children to private schools and buy life-long advantages. Only 7% of people are privately educated and yet they get most of the top jobs: 65% of senior judges, 59% of civil service permanent secretaries and 57% of the House of Lords all went to private schools.

- Wealth is also driving an explosion in second homes: an extra 100,000 in England over the 2010s. Meanwhile, young people without family wealth find it harder and harder to afford a decent first home.

And although most people make money from working, the wealthiest people don’t have to work at all – money does all the work for them.

- For example, Britain’s wealthiest family could earn over £4 million in interest every day without lifting a finger.

What mindsets is the Anti-meritocracy frame responding to?

People tended to think wealth earned through work had a privileged status: They were more positively oriented to earned wealth than to wealth you were ‘given’ or born into, or wealth that ‘earned itself’ (that is, wealth accruing from existing wealth).

Private schools are for the rich and a way of buying privilege: In conversations about what constituted ‘ordinary’ wealth, the consensus was that private education was not something that people with ordinary wealth could afford. Although private education was not necessarily seen as related to ‘extreme’ wealth, it was seen as a capacity not available to people with ordinary wealth. It was also recognised as enabling social privilege.

Anxiety around young people’s inability to access property and the link between property ownership and security: When asked to define what wealth meant, people often combined descriptions of ‘things’ (posh cars, big houses, luxury handbags) with non-material descriptions of ‘capacities’ that wealth was seen to unlock. People placed a lot of value on the security provided by having ‘a good home’. Younger generations were seen to find it more difficult than previous generations had to buy a home. There was an awareness that people were working very hard, but this was not delivering the security that it did for older generations.

Questions around the affordability of homes were a lightning rod for discussions of intergenerational unfairness and often used as evidence that things had become worse.

Dislike of ‘bad’ behaviours on the part of the rich: There was a general dislike of richer people being able to afford services (‘buying the best lawyers’) to help them avoid being accountable in the way that ‘we’ are. With regards to perceptions of extreme wealth and the extremely wealthy, contrasts were routinely made between ‘good’ billionaire behaviour (Bill Gates funding anti-malaria work) and ‘bad’ billionaire behaviours (Philip Green stealing pensions then sailing off on his private yacht).

How are these mindsets evident in the way people talk?

Bad sources of wealth + sense of economic insecurity + anxiety around property affordability + dislike of ‘bad’ behaviours (laziness) on the part of the rich:

“Any other words or associations that come to mind if I say wealth? Private school.” (London, left-leaning)

“I feel like there’s a difference between generational wealth, so being born into a family that’s rich and then actually working your way up... if you started from the bottom, you’ve worked your way up. You know how hard it is, so you’re probably not going to take things for granted.” (London, left-leaning)

“I think, also, the gap is massive. You’ve got the really very wealthy and you’ve got people who are basically on the breadline, so that gap... I think the opportunities are less for somebody who is on a low income than somebody who is very wealthy and has vast opportunities.” (York, left-leaning)

“I can’t right now imagine a time where I’m going to be able to afford a house, and I don’t think that’s based off me not working hard or anything to do with that. It’s just like, we have wage stagnation and rising house prices, both of which create this thing, and I’m choosing to live in London.” (London, left-leaning)

“So now my son is 26, he is finding it really difficult, like you are, he privately rents with his girlfriend and there’s 4 people in a property. There’s no way they could save up to get a mortgage because they pay out too much.” (London, left-leaning)

“I’ve actually seen his [Philip Green’s] yacht on holiday and he just sails around the Med doing nothing, and he stole that money from everybody, so it’s to do with the kind of character you are.” (York, left-leaning)

The Hoarding frame

Some people today are choosing to hoard their wealth: accumulating more than they could ever need instead of spreading it around.

- Britain’s wealthiest family could spend £100,000 every day for the next thousand years without running out of money.

When wealth is hoarded it hurts all of us – it starves our economy and harms our democracy.

- A leading financial institution, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), says that higher wealth inequality can lead to fewer people living healthy lives and getting the education they need – which also means lower economic growth.

- Wealth inequality can also create social unrest, such as protests by people who feel left behind.

What mindsets is the Hoarding frame responding to?

The importance of uses of wealth in making moral evaluations: Concerns about how wealth is used was the predominant means through which participants made moral judgements about wealth in our focus groups.

Recognition of hoarding as a ‘bad’ use: Several focus group participants demonstrated orthodox views of the economy and the role of wealth: Wealth was perceived to ‘trickle down’. It was felt that it needs to circulate in the economy so that everyone can benefit. Hoarding constitutes a ‘use’ of wealth that prevents these things from happening.

Dislike of hoarding of wealth when others are in need: Very few focus group participants were critical of amounts per se. They tended to make judgements based on context (how wealth is used and where it comes from). Having ‘extreme’ wealth was viewed negatively by some participants in contexts where others were in need.

Recognition that wealth inequality leads to polarisation and unrest: When discussing the social impacts of wealth inequality, people were concerned about social and spatial polarisation. They were aware that different areas were richer and poorer, and they were aware that differences in access to healthcare (that is, the ability or not to buy private healthcare) had an impact on health outcomes.

How are these mindsets evident in the way people talk?

Importance of use + dislike of hoarding + dislike of extreme wealth when others are in need + concern about social polarisation and unrest:

“... when it’s good, it goes round and round and round. You spent, well, it’s okay because it comes back round, and it goes round and round and round. The problem is, when there is somebody who has £60 billion or something, they might have investments and things, but quite a lot of the time the money is... just accumulating wealth rather than going around. That’s when for me it’s a problem.” (York, left-leaning)

“Also, you could have somebody, I suppose, who’s buying lots of properties to let out, then that means other people can’t get on the property ladder, I’d see that as unreasonable...” (York, right-leaning)

“When you think somebody spent £70,000 on a handbag... people have got so much money that they don't know what to do with it... that money could have gone to a youth centre, for example, or supported some sort of charity, homeless people.” (York, left-leaning)

“I think, that very few people have so much money and they are quite happily living in their bubbles, seeing the rest of the world suffer and spend money on frivolous things or whatever is in their interest rather than actually thinking about helping all these other countries. I don’t know how people can live like that.” (London, right-leaning)

“Access to health inequality, I suppose then if you have an NHS that has been on its knees for quite a long time, someone who’s solely using that in comparison to just solely using private healthcare, what you’re getting then is probably a difference in estimation of life. What you’ve got access to ultimately means that those with money may just live longer and better than those without money.” (London, right-leaning)

“It creates a divide. If you don’t have wealth… I don't know, like Tower Hamlets, Newham, certain boroughs, you can tell they’re a lot more deprived than other places in London.” (London, right-leaning)

York, right-leaning: [The riots were] happening in pretty much every city.

Interviewer: Do you think that’s related to wealth in any way?

York, right-leaning: Yes, potentially.

3. Pre-existing attitudes to wealth inequality

Insights from the survey experiment reveal that people have pre-existing strong views about wealth inequality.

Some of the people responding to our survey (the control group) were not shown any of our 3 frames.

Understanding the pre-existing public attitudes and beliefs expressed by this group allow us to understand the ‘shifts’ resulting from exposure to the 3 frames.

The attitudes expressed by this control group show us that:

- There is an existing strong public consensus that wealth gaps are too large:

- 78% of the control group agreed or strongly agreed that the wealth gap was too large.

- People are already strongly supportive of the idea that wealth should be more evenly distributed:

- 78% of the control group agreed or strongly agreed that it should be more evenly distributed.

- There is pre-existing strong support for increasing taxes on the rich, compared with spending more on welfare:

- 74% of the control group agreed that taxes on the rich should be higher

- 55% agreed that there should be more spending on welfare benefits.

- People are generally mistrustful of politicians and do not feel like they can influence politics easily:

- 72% of people either don’t trust them at all or only trust them a little

- 66% feel they cannot influence politics or can only influence it a little

- only 30% of people are satisfied with how democracy works in the UK and only 6% are very satisfied.

Variations within public attitudes in the control group

There are systematic variations within these public attitudes: grouping by income, voting history and sex reveals different attitudes to wealth, redistribution and politics more generally.

| Orientation to wealth | Support for redistribution | Attitudes to politics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-income earners (<£19,000) | More critical | More supportive | More negative |

| High-income earners (£63,000 – £199,000) | Less critical | Less supportive (of taxing the rich more) | More positive |

| Top income earners (>£200,000) | Less critical | More supportive (of welfare spending) | More positive |

| Left-wing voters | More critical | More supportive | More positive |

| Right-wing voters | Less critical | Less supportive | More positive |

| Women (vs men) | More critical | No differences | More negative |

4. The effects of the frames in detail

When discussing the results of exposing people to different narratives (or ‘frames’) about wealth, we have focused only on shifts that were statistically significant.

This means that, based on our study, we can be at least 95% certain that a shift in opinions occurred for those who were exposed to a certain narrative and not for those who were not exposed to this narrative. This is what we call the ‘treatment effect’. For more detail see Annex 1.

Political attitudes

As well as the main views described in Figure 2, we also wanted to check whether our frames had any effects on political attitudes in a range of areas related to trust and democracy. In Figure 3, we summarise these results.

The Anti-meritocracy frame and the Hoarding frame had no effect on political attitudes.

The Unfair Influence frame reduced trust in politicians and satisfaction with democracy. We have discussed the implications of this finding in chapter 5 - Results commentary.

What effects does the Unfair Influence frame have?

The results show overwhelmingly that the Unfair Influence frame is effective at increasing critical orientations to wealth. Respondents who read the Unfair Influence information:

- increased their support for the statement that the wealth gap is too large

- reduced their support for the statement that wealth has a positive impact on society

- reduced their support for the statement that wealth is a result of hard work and talent.

It is effective at increasing support for some forms of redistribution. Respondents who read the Unfair Influence information:

- increased their support for the statement that wealth should be more evenly distributed

- increased support for the statement that ‘taxes on the rich should be higher’.

Respondents who read the Unfair Influence information did not increase their support for the statement that ‘There should be more spending on welfare benefits’.

The frame affected political attitudes by:

- making people less trusting in politicians

- making people less satisfied with how democracy works.

What effects does the Hoarding frame have?

The results show that the Hoarding frame is effective at increasing some critical orientations to wealth. Respondents who read the Hoarding information:

- reduced their support for the statement that wealth is a result of hard work and talent.

Respondents who read the hoarding information:

- did not change their views on redistribution

- did not change their political attitudes.

What effects does the Anti-meritocracy frame have?

The results show that the Anti-meritocracy frame is effective at increasing critical orientations to wealth. Respondents who read the Anti-meritocracy information:

- increased their support for the statement that the wealth gap is too large

- reduced their support for the statement that wealth is a result of hard work and talent

- reduced their support for the statement that wealth has a positive impact on society.

Respondents who read the Anti-meritocracy information:

- did not change their views on redistribution

- did not change their political attitudes.

5. Results commentary

In this commentary, we discuss the survey experiment results in the context of the conversations from which the ideas for the frames arose – namely the expert convenings – and the focus groups in which the frames were refined (see the Methodology and results appendix). The results themselves are summarised in the first part of the Executive summary.

Good and bad wealth

Lead on the bits that people experience most as ways into the discussion and then link this to the broader systemic analysis.

A key question is whether people distinguish the kinds and amounts of wealth that provide security for ordinary people (‘ordinary’ wealth) from the kinds and amounts of wealth that cause social and environmental harm (‘extreme’ wealth).

In our research, focus group participants found the distinction between ‘ordinary’ and ‘extreme’ wealth to be meaningful. But we also found that very few people (across different demographics) saw wealth as ‘purely or mostly’ a good or bad thing. This was overwhelmingly dependent on how it was used, and where it came from/how it had been acquired (source).

We took forward the idea of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ uses and sources into our frames. As the results show, the most successful frame (Unfair influence) brings together both a particular ‘bad’ use (power and influence) with unfair sources of enrichment (insider connections and tax avoidance), which resonated strongly with the survey participants and led to stronger critical orientations to wealth inequality, and stronger support for redistribution.

There are potential risks in this kind of more context-specific evaluation of wealth, including: fragmenting our understanding of wealth inequality into different issues or even maintaining space for defensive strategies by extreme wealth holders (such as increasing focus on their ‘good’ uses like philanthropy).

Yet leading on bad uses and sources, as we did across the frames, then linking to a broader systemic analysis, demonstrates that such framing can increase support for systemic solutions like redistribution.

Security, fatalism and trust

Recognise and constructively engage fatalism. It is the dominant mindset and ignoring it offers space for alternative populist narratives to take hold.

The social safety net – pensions, housing, health and social care – has been progressively privatised at the same time that people have been told that they are responsible for themselves. In this context, securing private wealth becomes a rational response to the lack of a social safety net, particularly the drive to own a home.

This ‘security’ mindset was strongly reflected in focus group conversations where concerns around house prices, affordability and availability dominated parts of the conversations where people talked about whether things had become better or worse. Security was also prominent in how people defined wealth – in addition to the ‘things’ you buy, they saw wealth precisely as a means to achieving security, health and well-being.

Feelings of insecurity are evident not just in how people think about their own lives, but also in people’s pessimism about wider social and economic conditions. Overwhelmingly, when asked if they felt things were getting better or worse, our focus group participants said they were getting worse (the ratio of negative to positive comments was 12 to 1 and was particularly pronounced in right-leaning groups).

London, right-leaning: It’s just not going to get any better. It’s going to get worse. It’s not going to be for us people, working-class people. We’re not going to go up the line any much further. There's no way out basically. I can’t see a way out of it.

A key concern with ‘System is rigged’ or Unfair Influence framing is that it might risk triggering pervasive fatalism – ‘I can’t see a way out of it’. This could lead to a dampening effect on democratic engagement: if you do not believe that things can get better, why bother trying to make them so? Yet our results (see Table 3) show a nuanced picture: the Unfair Influence frame does indeed decrease trust in politicians and satisfaction with democracy, but it does not decrease so-called ‘external efficacy’ (that is, the degree to which people feel like they can influence politics).

Of course, people will place different levels of importance on attitudes like trust in politicians or satisfaction with democracy. We would only draw attention to the fact that despite the frame affecting some political attitudes negatively, it also increased support for redistribution and higher taxes on the rich. And lower satisfaction with democracy is also a common predictor of increased political participation and mobilisation – which can end up being positive for democracy itself.

It is important to be aware that this mindset about the system being rigged is dominant, and needs to be recognised and engaged constructively.2 Failing to do so leaves it open to being co-opted by harmful far-right populist narratives:

“... failing to engage with it means ceding it to those who would aim it in exclusionary directions and use it to fuel support for xenophobia, authoritarianism, and racism. People will draw on this mindset – our research clearly shows this. If progressives don’t contest the meaning of this mindset by explaining how the system is rigged in ways that align with a progressive diagnosis and vision, this lets those advancing oppression and injustice fill in the blanks.” (Volmert and Blustein, 2025, p.12)

Meritocracy and other existing beliefs

Do not assume that prevailing mindsets like meritocracy are immutable: they can be shifted with convincing evidence and frames.

How can problem definitions, attributions of causation, moral judgements and the articulation of solutions avoid triggering strongly held beliefs that are likely to decrease rather than increase support for change?

It can sometimes feel as if dominant mindsets are inescapable, particularly the idea that inequalities in areas like wealth are meritocratically deserved (earned through hard work and/or talent), and that as a result, the status quo is fair. This helps to explain low support for redistribution in contexts of rising inequality.

Politicians on the right and left have popularised meritocracy: it pervades the media and popular culture, as evidenced by rags to riches stories. It is supported by tropes and metaphors such as ‘pulling oneself up by the bootstraps’, ‘the level playing field’ and ‘a rising tide lifts all boats’.

We hoped that focusing on wealth – as opposed to income – would enable an easier critique of meritocracy (because it is more linked to luck, such as via inheritance). Focus group participants did indeed point to the role of luck and timing in acquiring wealth – especially the generational differences in how easy or hard it is to get secure housing. Yet they showed how difficult it is to separate people’s understanding of wealth and income. Participants often found their way back to incomes and salaries (for example, how much more a company director earns than a worker).

Notwithstanding this uncertainty around the distinction between wealth and income, in the survey experiment, the Anti-meritocracy frame that we built to respond to these ideas worked well in increasing critical orientations to wealth – specifically to the idea that wealth is a result of hard work and effort. It is therefore possible to engage with and undermine meritocracy. However, it is worth noting that this frame did not manage to simultaneously increase support for redistribution.

The role of evidence and sources

Seek out and expand on convincing evidence that lays out the scale of wealth inequality, and links wealth inequality to harms which people care about.

The topic of wealth inequality mixes together factual claims (for example, how much inequality is there), complex causal explanations (for example, how did this inequality come about) and irresolvable normative debates (for example, how much inequality is too much). In a topic like this, convincing evidence can play an important role.

We designed our frame treatments specifically to draw on some of this kind of evidence, but it is important to emphasise that this complicates interpretation and direct comparisons between the frames. Even though we tried to keep the ‘messengers’ communicating key evidence broadly comparable across the different treatments (for example, the G20 in the Unfair Influence frame and the IMF in the Hoarding frame), some claims have more supporting evidence than others.

In particular, the Hoarding frame showed the fewest effects in our experiment: we note that this frame was also the most challenging to supplement with convincing supporting evidence (that is, that hoarding wealth directly harmed the economy and democracy). This points to the importance of not just bringing effective supporting evidence and expertise to bolster your chosen frame, but also of generating further research to fill the gaps where such evidence is lacking.

Annex: Experimental and focus group design – technical notes for readers

Survey experiment design

To run our survey experiment, we collaborated with Qualtrics to access a standing online research panel suitable for quantitative studies. A ‘standing panel’ is a pre-recruited group of respondents who agree to participate in multiple survey waves over time.

Qualtrics facilitated the recruitment of participants who would then complete our survey in an online format. Our sample comprises a total of 2,000 participants split into 4 even groups of 500 participants. These groups were 1) the control group and 2) the 3 treatment groups.

Treatment groups correspond to the 3 different narratives we exposed people to (Unfair Influence, Anti-meritocracy, Hoarding). Participants were randomly selected into one of the 3 treatment groups or the control group at the start of the survey.

Our sample of participants is balanced across gender, meaning we surveyed about 1,000 women and 1,000 men. We also achieved a balanced spread across age, with our average participant being 46 years old and ages ranging between 18 and 87 years old. For other criteria such as education, ethnicity or annual income, we used population quotas, meaning our sample reflects the general distribution of those characteristics in the UK.

Survey experiment sample

A majority of participants had completed tertiary education (66%), with 33% having secondary education and less than 1% primary education only. Around 22% of participants had an annual income below £19,000 and around 60% earn between £19,000 and £63,000. 16% fell within the £63,000 up to £199,000 bracket, and around 2% fell into the top income bracket of £199,000 and above.

More than half (54%) of our sample worked in full-time employment, 11% in part-time employment or self-employment. In terms of ethnicity, 86.7% identified as White English, Welsh, Scottish, Northern Irish or British, or White other; 7.3% identified as Asian or Asian British; 3.3% as Black or Black British or Caribbean; 2.2% as mixed or multiple ethnic groups and 0.5% as other ethnic groups.

Measurement of experimental variables and treatment effects

Questions were organised around 3 topics: critical orientations, support for redistribution and political attitudes.

Critical orientation encompassed the following statements:

- ‘The gap between those with lots of wealth and those with little wealth is too large.’

- ‘The way people use their wealth in the UK has a positive impact on society.’

- ‘The reason why some people in the UK have more wealth than others is because of hard work and talent.’

Statements were evaluated on a scale from 0 to 10. 0 stood for strong disagreement and 10 for strong agreement with respective tendencies in between those endpoints where positions around 4, 5 and 6 would be more neutral.

When looking at effects, we thus observe opinion shifts as movement up or down that scale. For simplifying purposes, we treat evaluations on a continuous scale, hence we observe opinion shifts as decimal shifts, most of them falling within +/- 0.5 and 1-point changes if significant.

Support for redistribution encompassed the following statements:

- ‘I would like to see wealth more evenly distributed.’

- ‘Taxes on the rich should be higher.’

- ‘The government should spend more on welfare benefits.’

Statements were evaluated on a continuous scale (that means the increments were not set, for example, by 10 steps) from 0 to 100. 0 stood for strong disagreement and 100 for strong agreement, and positions between 40 to 60 were more neutral.

When looking at effects, we thus observe opinion shifts as movement up or down that scale. For simplifying purposes, we treat evaluations on a continuous scale, hence we observe opinion shifts as decimal shifts, most of them falling within +/- 5 and 10-point changes if significant.

Political attitudes encompass the following statements:

- ‘How much do you trust politicians generally.’

- ‘How much does the political system in the UK allow people like you to have an influence on politics.’

- ‘How satisfied are you with the way that democracy works in the UK.’

Statements were evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale. One stood for not at all/very dissatisfied and 5 for a great deal/very satisfied.

When looking at effects, we thus observe opinion shifts as movement up or down that scale. For simplifying purposes, we treat evaluations on a continuous scale, hence we observe opinion shifts as decimal shifts, most of them falling within +/- 0.05 and 0.10-point changes if significant.

When discussing the results of exposing people to different narratives (or ‘frames’) about wealth, we have focused only on shifts that were statistically significant.

This means that, based on our study, we can be at least 95% certain that a shift in opinions occurred for those who were exposed to a certain narrative and not for those who were not exposed to this narrative. This is what we call the ‘treatment effect’.

In Figure 4, we visualise the treatment effects from our 3 frames across 9 different variables. In these visualisations, the dots represent the estimate of the size of the effect, with the lines to either side representing the 95% confidence intervals. Models used to estimate effects included a range of standard demographic control variables such as age, sex, education and income, which are not visualised here.

Methodology and results appendix

We recruited participants for our focus groups using a qualitative research agency (Acumen). We conducted 4 groups: 2 based in London and 2 in York. Within each location, we recruited one group with more ‘economically left-leaning’ participants and another with more ‘economically right-leaning’ participants, based on screening questions around tax and welfare spending. Participants otherwise had a mix of age, income, ethnicity and sex, and some diversity of voting history. Below you can download the full methodology and results.

Notes

- See work by FrameWorks and FrameWorks UK on mindsets, what they are and how to work with them.

- We recommend looking at the approaches discussed in Hebden (2025) and Volmert and Blustein Lindholm (2025).

References

Entman, R.M. (1993) Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm

Hebden, P. (2025) The Wealth Tax campaigners have a blueprint for responding to fatalism

Volmert, D. Blustein Lindholm, C. (2025) Filling in the blanks: Contesting what ‘the system is rigged’ means

Acknowledgements

This report and the work underpinning it is a collective endeavour. Along the way we have benefited from the input of some fantastic colleagues. Firstly, to the participants in our workshops series in 2024 who shared their ideas and experiences to help us identify the different mindsets at play. We’d like to acknowledge the input of colleagues from the International Inequalities Institute and the Centre for the Analysis of Social Exclusion who gave us feedback on the first draft of the literature review and online report. To our advisors and/or focus group co-convenors, Frank Soodeen (JRF), Natalie Tate (JRF), Dan Stanley (Future Narratives Lab), Dora Meade and Enez Nathie (NEON), Will Snell (Fairness Foundation), and Paul Hebden (Campaign Salience). They have given time and expertise to help test ideas as we’ve gone along. We’d like to recognise that here. Thanks to JRF and LSE for funding this stream of work.

About the authors

Although this report is authored by Sarah Kerr, Michael Vaughan and Annalena Oppel from the International Inequalities Institute, London School of Economics, it is based on a multifaceted research project which different people have contributed to in different ways. We would like to recognise the different contributions people have made here:

- theme development: literature review – Kerr and Vaughan

- report – Kerr and Vaughan

- Radical Imaginings Workshops conception, design and convening – Kerr and Vaughan

- focus group topic guide design – Vaughan, Kerr, Dora Meade, Dan Stanley, Will Snell

- participants and presenters at RI workshops; Focus group design and recruitment – Vaughan, Kerr, Meade, Stanley, Snell

- focus group convening – Vaughan, Kerr (with Enez Nathie, Meade and Stanley)

- focus groups data coding and thematic analysis – Kerr with Vaughan

- testing: survey experiment design – Vaughan, Oppel, Kerr (with Meade and Stanley)

- survey data interrogation and analysis – Oppel and Vaughan with Kerr

- reporting: report design – Kerr, Vaughan, Oppel

- report content development – Kerr, Vaughan, Oppel

- report writing – Kerr, Vaughan, Oppel.

How to cite this report

If you are using this document in your own writing, our preferred citation is:

Kerr, S., Vaughan, M. and Oppel, A. (2025) Talking about wealth inequality. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation

This report is part of the narrative change topic.

Find out more about our work in this area.